The internet today is full of intricately produced videos, realistic digital art, and endless musical creations and remixes. But for many artists, the creative medium that captures their imagination is an old-fashioned, DIY print format: The zine.

Having first begun in the 1930s through science fiction fandoms, zines really took off in the 1960s with the invention of the mimeograph—one of the first reproduction mediums beyond carbon paper. Zines continued to rise in popularity as Xerox machines became widely used in offices and schools. These technologies made it easier than ever to make paper copies of short, limited-run, self-published work for distribution.

In the days before the internet, zines were primarily created as a way of spreading a message the creator was passionate about and finding a community of like-minded people. Although the internet has now largely taken over those responsibilities, zines still exist today as art projects, as a tactile creation experience, and as a nostalgic means of communication.

While zines were—and are still—made throughout the country, the Midwest broadly and Central Ohio specifically remain havens for zinesters.

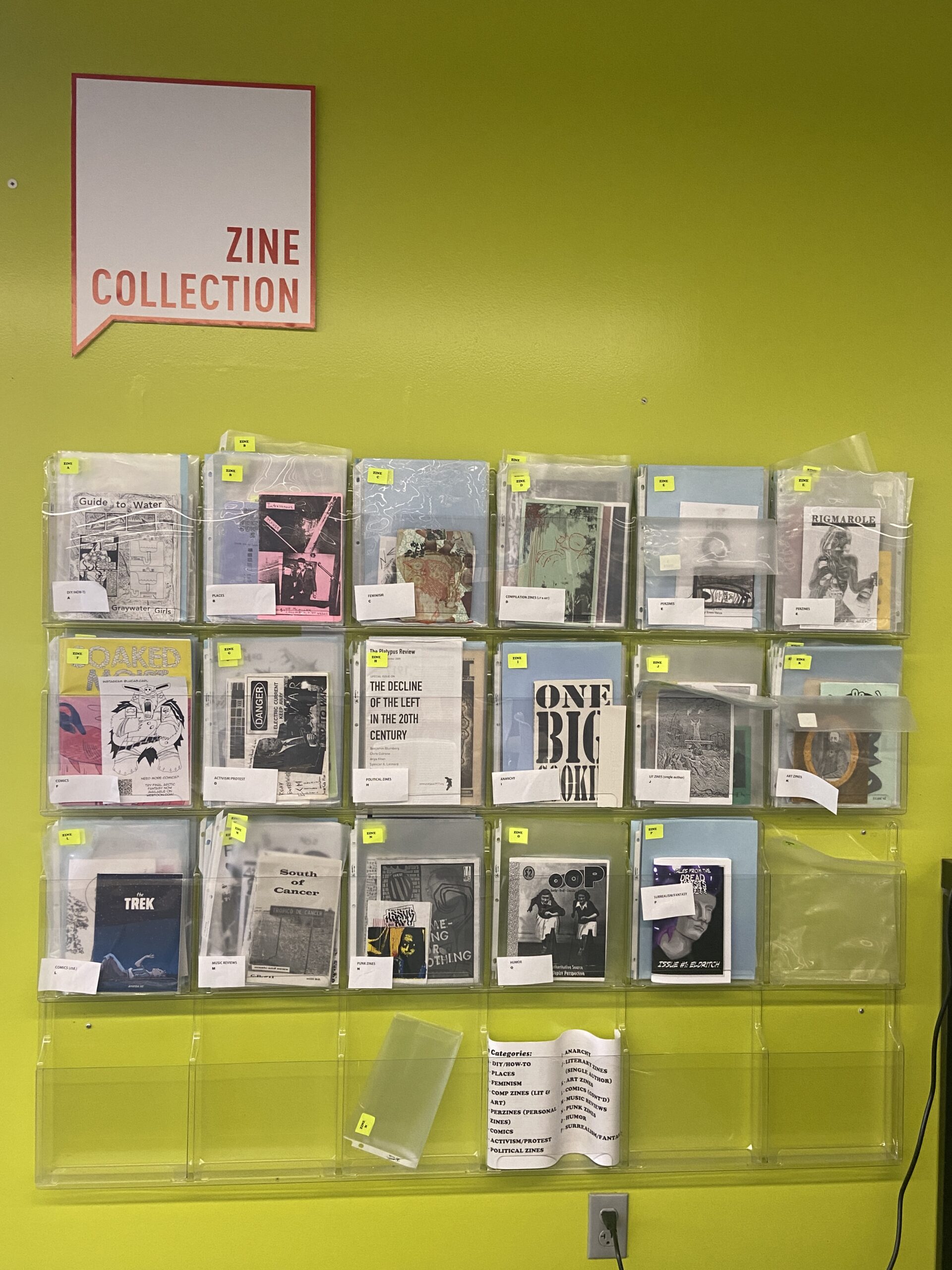

“Zines are such a flexible medium they can be used for anything,” said Christine Mannix, a librarian at the Columbus College of Art and Design (CCAD) in Columbus, Ohio, which has a sizable zine collection. Because it’s an art school, several classes at CCAD—from illustration to bookmaking, and from art history to poetry—have students browse the zine collection and then make their own for assignments.

The collection at CCAD is a representative sample of the landscape of zine-making from the past 30-40 years. Zines range from palm-sized to full 8½-by-11 booklets and from handsewn closures to staple bindings. They can be the black-and-white Xerox punk style popularized in the 90s or full-color, as well as text-only, art-only, or a mix of both. The art styles vary immensely from comics to photography and from collage to graphic design.

Fiction Zines Tell True Stories

The content of the zines is even more varied. The collection at CCAD covers anarchism, transportation, feminism, fiction, poetry, memoir, gender, sexuality, recipes, music, protest, DIY tips, satire, and more. There are few rules that define zines, which lend the format to nearly endless creative possibilities.

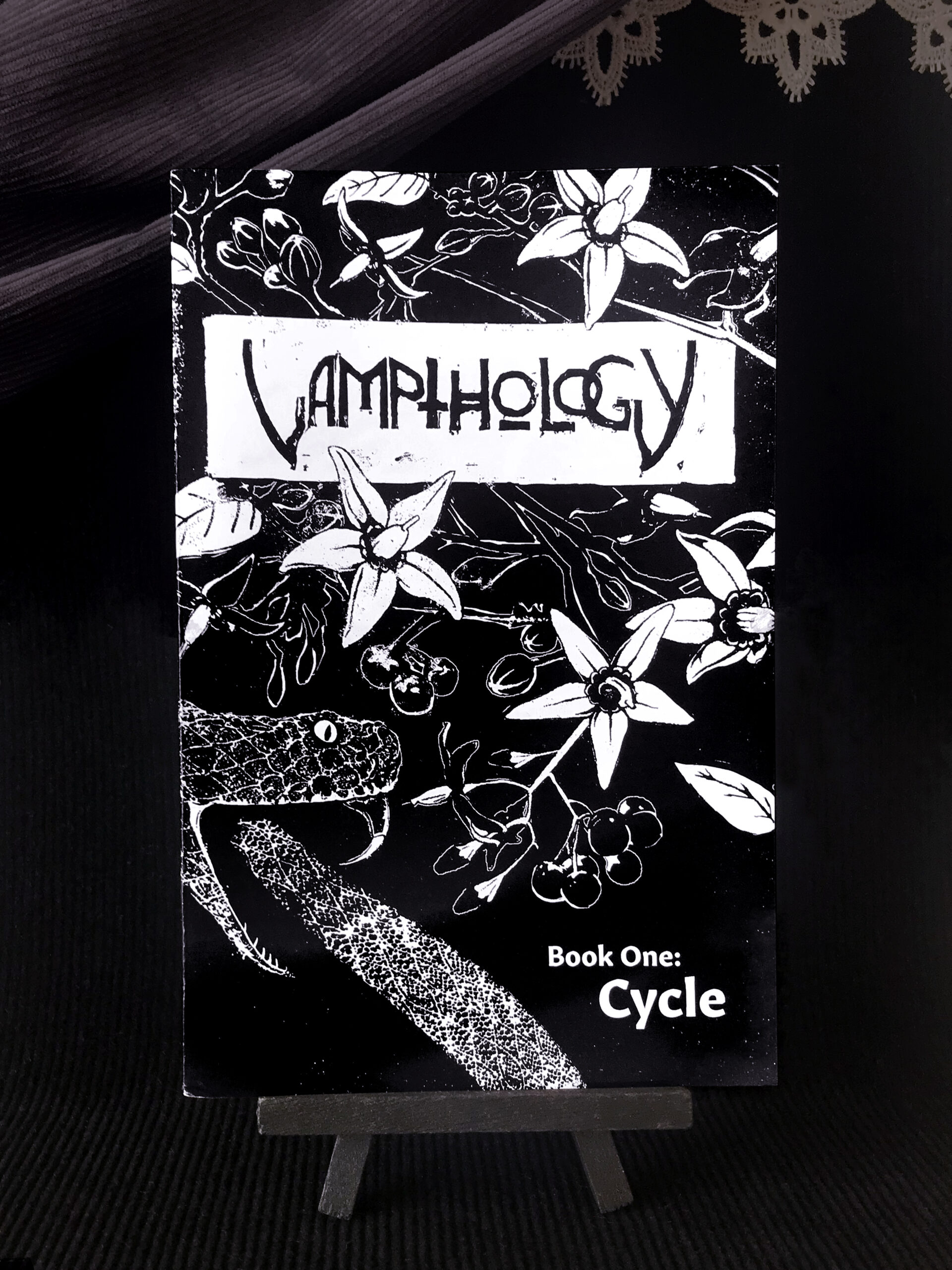

It’s exactly this freedom that inspires Eric Clift-Thompson, a professor at CCAD, to make zines. Their first zine, Vampthology, was the thesis project for their MFA and how they first fell in love with the medium.

“I wanted to tell a story with pictures, but I didn’t want it to be a picture book or comic in the traditional sense,” Clift-Thompson said. “And I definitely wanted it to be short stories because there were so many different conversations I wanted to have within the same book. A zine is almost whatever you want it to be, so it gave me permission to make something I thought was cool and interesting rather than sticking to what I thought a comic had to look like.”

ERIC CLIFT-THOMPSON, PROFESSOR AT COLUMBUS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN“A zine is almost whatever you want it to be, so it gave me permission to make something I thought was cool and interesting …”

For Clift-Thompson, an illustrator, printmaker, graphic designer, and writer, Vampthology allowed them to combine the mediums they love into one project. While the zine is printed, the combination of mediums also allowed them to make the zine accessible when posted online.

Vampthology is deeply personal for Clift-Thompson because the lens of vampires allowed them to articulate their experience as a trans person.

“After playing a game of Vampire: The Masquerade in undergrad, I started thinking about monsters and queerness, loss, and the way vampire transformations can change your body. The process that a vampire might go through is similar to the uncomfortable process of transitioning,” Clift-Thompson explained.

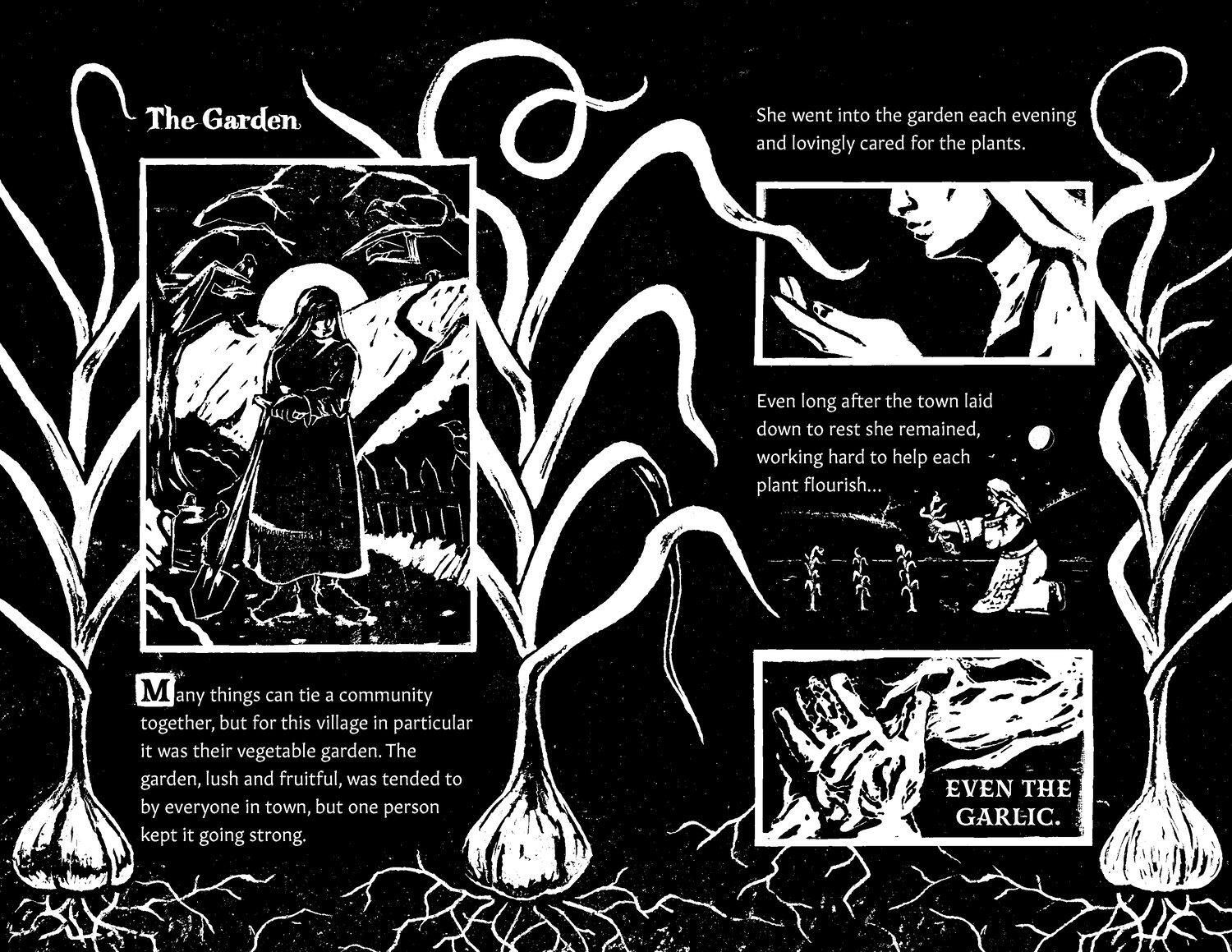

One of the short stories in Vampthology is about a vampire who’s living undercover in a human community and gets outed as a vampire. In an attempt to remain in their community, they cite how they lovingly tended the garden, even the garlic they couldn’t eat.

“All the stories were very personal in different ways but that one was connected to my experience growing up in my parents’ church and being outed to them and the heartbreak that came from that … Even though I knew how they felt about gay people in general because they knew me personally, I thought they wouldn’t feel the same about me. Their opinion of me changing so quickly really stuck with me,” Clift-Thompson said.

The experience of creating Vampthology was so gratifying that Clift-Thompson has gone on to make several more zines, including I Am Grotesque, a meditation on how trans bodies are described in art history; Girls, Girls, Gore, a juxtaposition of the erotic in pinup art and the grotesque that interrogates notions of femininity; and a zine on Belle Gunness, a serial killer in Indiana in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Gunness was written about in the newspaper as being tall, strong, and masculine in appearance, thus giving rise to theories that it was her male qualities that made her capable of murder.

Zine Fests Build Community

Both the format and content of Clift-Thompson’s zines speak to how the medium functions in the present day as an art object that communicates in a short, compelling way. The often deeply personal stories shared in zines still set out to achieve what zine-makers have always sought to do in their work: find their people.

“For me, that made the zine satisfying. I wasn’t designing a logo for someone or doing what I was ‘supposed’ to be doing. It was indulgent,” Clift-Thompson said. “That’s what I love about zines. You’re making something you care about and putting it out into the world to find your people. What I wanted at the end of this was a sense of community.”

Community is also what Stephanie Renner and Zak Biggard want, which is why they both run art collectives whose main event is an annual zine festival. Biggard, along with his friend Dustin Bennett, created Bazaar Ritual, an art collective that in addition to organizing shows at Global Gallery, a fair-trade coffee shop in Columbus, Ohio, also organizes a zine swap every October.

STEPHANIE RENNER, ZINE-MAKER AND ORGANIZER OF THE STREET CAT ZINE FEST“DIY is for everyone but it’s especially for people who don’t have a voice any other way, who don’t have other ways to speak up for themselves or have access to other things because of a barrier to entry.”

It’s one of Biggard’s favorite events the collective does because he’s a zinester himself.

“Mine are always art zines since I’m not much of a writer. I went to school for illustration and I’ve been an active artist since high school. My zines range from comics to super abstract art. Each one is different and I try to go radically in one artistic style for each one,” Biggard said.

“It’s not something I can do more than a couple of times a year and I try to put a lot of time and effort into them,” he added—something that Clift-Thompson and nearly all zine-makers can relate to.

Typically, the zine swap takes place in person at Global Gallery. Zine-makers get together to trade their work and enthusiasts come to purchase copies for their collections. It’s a diverse crowd, not just in terms of the work presented but in the identities of the creators. As Biggard describes those who attend, “It’s people I’d have never met otherwise. People from every walk of life.”

Zines Bring Rural Communities Together

Renner’s event, Street Cat Zine Fest, seeks to bring rural zine-makers and enthusiasts together. Now based in Chillicothe, Renner’s hometown about an hour outside Columbus, they have made and distributed zines in the Athens/Nelsonville area and organized zine festivals in other rural towns in Central Ohio, including Lancaster, since 2017.

“In Lancaster and Chillicothe both, I didn’t know other people who made zines. That’s what inspired me to make a zine fest,” they said, recalling the first zine fest they went to, which was a long drive away in Scranton, Pennsylvania. After visiting other zine festivals in Kentucky, Indiana, and Michigan, Renner wanted to bring a zine fest to rural Ohio.

“I did it out of wanting to help create a community that really wasn’t there,” they said. “The idea is to try to expose people to zines so hopefully they’ll want to try it. The festival was a lot of artists and zinesters all supporting each other, but we also had a lot of random people come by and that’s what I want. I want people to be curious and wonder what we’re doing.”

For Renner, who was immediately intrigued by zines after first encountering some in a restaurant in Athens, it’s important to recreate that sense of creativity capability in others.

“I was drawn to the idea that I could be the media. I don’t just have to consume something, I can make something,” Renner said.

This is no surprise to Mannix, who has been a librarian for years and has seen continued interest in zines.

“I think the appeal of zines now is the making of them, not necessarily the communications aspect,” Mannix said. “People want to make something physical. I see students who are tired of working on the computer and just want to engage in something with their hands.”

In addition to being rewarding to make, the accessibility of zines makes them especially appealing to people in marginalized communities. As Renner explained, “DIY is for everyone but it’s especially for people who don’t have a voice any other way, who don’t have other ways to speak up for themselves or have access to other things because of a barrier to entry.”

Between the many zine-makers who perpetuate the art form, the zine festivals that allow creators to connect and distribute their work, and the zine librarians who collect and preserve these limited-edition artworks, zines will continue to endure for generations to come.