Esta historia está disponible en español. Para leer en español, haga clic aquí.

When artist Marissa Hernandez applied for a job as a mural assistant in college, she had no idea it would change her life.

“I stumbled upon the mural assistant job and applied, not thinking I’d get it, then later people started seeing my work when I posted it online,” Hernandez says. “The Des Moines community and social media got me started. Then it kept building upon itself.”

Today, Hernandez has a dozen murals in and around the Des Moines area where she grew up. But there’s one that’s particularly close to her heart: the murals she painted in rural Hampton, Iowa, one on the side of a vintage shop, and the other on the side of La Luz Centro Cultural, a Latino community center.

An hour and a half north of Des Moines, the small town of Hampton is 40 to 50% Hispanic and Latino. As the daughter of a Mexican immigrant, Hernandez jumped at the chance to paint a mural in the town.

“I’m Latino myself, so it was a cool project to be able to do, and it was the first time I’d traveled and stayed overnight to do a mural,” Hernandez says.

But before she puts paint to canvas—or, in this case, brick—Hernandez has a design process that helps her capture the space’s energy.

“I like to think about the mood you want the mural to evoke. Do you want viewers to be energized, happy, or calm? We talked about community, so I thought about how you show community in a visual way,” Hernandez explains. “We landed on a design that has people at the forefront but also has a mix of native Iowa wildflowers and Latin American plant life to really show the blend of the Hampton community and their culture and the Iowa culture as well.”

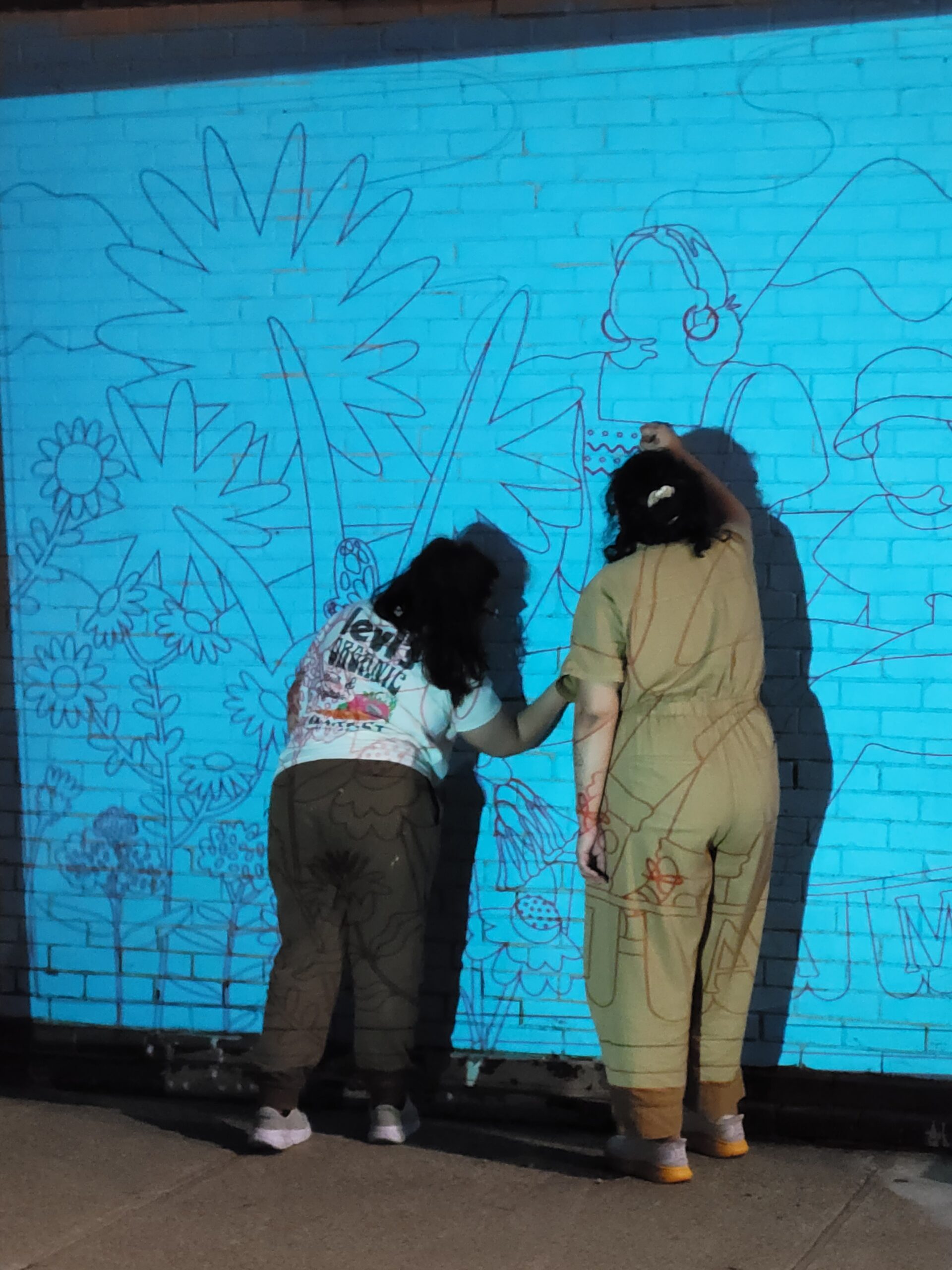

In true community fashion, Hernandez took an “it takes a village” approach to painting her mural by inviting the local kids hanging out at La Luz to help.

“It was great working with the kids; they were really good painters! I liked how fearless they were,” Hernandez remembers. “I know I was so nervous when I first started painting my first mural where I was the assistant, but they just jumped right in and were super helpful.”

Inviting the local kids to take part not only got them into the creative spirit and allowed Hernandez to complete the mural more quickly—“They got a lot done!” she noted—it fostered a real sense of community ownership in the project.

“I like how when the kids bring their family back they’re able to say, ‘I worked on that banner portion,’ or ‘I worked on the sleeve of this shirt,’” Hernandez says. “That’s probably the coolest part, just seeing how proud they are of themselves. As they should be because they helped make this thing that will be in their community for a long time.”

Viewers will notice something unique about Hernandez’s portraits in the mural: they’re faceless. That’s by design.

“I want to make portraits of the BIPOC community, but I don’t care as much about who the portrait is of as long as it makes someone feel represented. That’s how I jumped onto the faceless portraits. Anyone can project their own face on the figure they most identify with and feel represented. And they might see other figures and think, ‘Hey, that looks like my friend, mom, or grandma.’ That’s really important to me,” Hernandez says.

For Leon Kuehner, Executive Director of the Iowa Alliance for Arts Education, the mural is exactly what everyone was hoping for.

“When [La Luz] received a We the Many grant, there were a bunch of us sitting there brainstorming. We really wanted something that would have a lasting impact on the community,” he says. “A mural is perfect because there’s a daily tangible record of what that money helped get accomplished.”

Kuehner lives in Hampton, and in addition to helping facilitate Hernandez’s mural, he’s been able to use grant funds to support a variety of Hispanic and Latino arts programming in the area. Having directed various bands and choirs at the high school and college level for decades, Kuehner is especially excited to have been able to bring up-and-coming opera singer Mario Arévalo to town.

Originally from El Salvador, Arévalo now lives in Miami and took a weekend to visit Hampton, spending time working with student soloists from several choirs in the area and putting on a performance alongside the students that was open to the public.

“The concert he did was music from all central and South America. Music from Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Cuba, and El Salvador,” says Keuhner. “A comment we heard a lot was, ‘Wow, I see someone who looks like me singing opera.’”

Arévalo was so well-received in Hampton that he’s already planning a return trip in spring 2024.

“Arts and culture is what brings people together. When you have a diverse community, those are the things everybody loves,” says Kuehner. “And it’s all related. Like Marissa doing the faceless portraits and being able to project yourself onto that. Students can say, ‘Yes, I can make art. I can make music. I can make a living as an artist.’”

LEON KUEHNER, IOWA ALLIANCE FOR ARTS EDUCATION“Arts and culture is what brings people together… Students can say, ‘Yes, I can make art. I can make music. I can make a living as an artist.’”

Murales Unen a la Comunidad Latina de Hampton, Iowa

Marissa Hernandez invitó a jóvenes de esta pequeña comunidad para ayudarle a pintar murales que amplían la cultura y la representación.

Cuando la artista Marissa Hernandez solicitó empleo como asistente muralista en la universidad, no tenía idea que le cambiaría la vida.

“Me topé con un trabajo de asistente muralista y lo solicité, sin pensar que lo obtendría, luego la gente empezó a ver mi trabajo cuando lo publicaba en línea”, dijo Hernandez. “La comunidad y medios sociales de Des Moines lo pusieron en marcha. Y de ahí creció por sí mismo”.

Hoy en día, Hernandez ha creado una docena de murales en Des Moines y sus alrededores, donde se crió. Pero hay un proyecto que está particularmente cercano a su corazón: los murales que pintó en Hampton rural, Iowa; uno, al costado de una tienda de antigüedades, y el otro, al costado de La Luz Centro Cultural, un centro comunitario latino.

A hora y media al norte de Des Moines, la población en la pequeña ciudad de Hampton es entre 40 a 50% hispana y latina. Como hija de inmigrante mexicano, Hernandez no dejó pasar la oportunidad de pintar un mural en la ciudad.

“Soy latina, así es que me parecía genial poder realizar el proyecto, además, era la primera vez que viajaba y me quedaba a pasar la noche para pintar un mural”, dice Hernandez.

Pero antes de aplicar la pintura en la tela — o, en este caso, sobre ladrillo — el proceso de diseño único de Hernandez le ayuda a capturar la energía del espacio.

“Me gusta pensar en el estado de ánimo que quieres que el mural evoque. ¿Quieres que los observadores se sientan energizados, alegres o calmados? Nos referimos a la comunidad, entonces pensé en cómo mostrar a la comunidad visualmente”, Hernandez explica. “Nos decidimos por un diseño que tuviese a personas al frente, pero también una mezcla de flores silvestres nativas de Iowa y la vida vegetal latinoamericana que mostrase una real armonía entre la comunidad y la cultura de Hampton, con la cultura de Iowa”.

Al más puro estilo comunitario, Hernandez adoptó el enfoque “se necesita a todo un pueblo” para pintar el mural, e invitó a niños locales que frecuentan La Luz para que le ayudaran.

“Fue genial trabajar con estos niños; ¡realmente eran buenos pintores! Me encantó lo valientes que fueron”, recuerda Hernandez. “Recuerdo haber estado muy nerviosa cuando comencé a pintar mi primer mural, en el que era asistente, pero los chicos se metieron de lleno y fueron súper útiles”.

Al invitar a los niños locales a que participaran, no sólo los sumergió en el espíritu creativo permitiéndole a Hernandez completar el mural más rápido — “¡Hicieron un montón!” indicó — fomentó, además, un verdadero sentido de propiedad comunitaria en el proyecto.

“Me encanta ver cuando los niños le muestran a sus familias, y pueden decir, ‘Yo trabajé en esa porción del banner’, o ‘yo trabajé en la manga de esa camisa’”, dice Hernandez. “Esa es probablemente la mejor parte, ver lo orgullosos que se sienten de ellos mismos. Como debería ser, porque me ayudaron a realizar eso que estará presente en su comunidad por mucho tiempo”.

Los observadores notarán algo único sobre los retratos en el mural de Hernandez: no tienen rostros. Así es el diseño.

“Quiero hacer retratos de la comunidad BIPOC [afroamericanos, indígenas, personas de color, por sus siglas in inglés] pero no me importa mucho de quién sea el retrato, siempre y cuando alguien se sienta representado. Así es como decidí hacer retratos sin rostro. Cualquiera puede proyectar su propio rostro en la figura con la que se sienten más identificados y representados. Y podrían ver otras figuras y pensar, ‘Oye, ese se parece a mi amigo, a mi mamá, o a mi abuela’. Eso es realmente importante para mí”, dice Hernandez.

Para Leon Kuehner, Director Executivo de la Alianza de Iowa para la Educación Artística, el mural es exactamente lo que todos esperaban.

“Cuando [La Luz] recibió la subvención We the Many, habíamos varios sentados pensando en las distintas posibilidades. En realidad queríamos algo que tuviese un impacto duradero en la comunidad”, dice. “Un mural es perfecto porque hay un registro tangible diario de lo que el dinero ayudó a lograr”.

Kuehner vive en Hampton, y además de ayudar a que el mural de Hernandez fuese posible, ha usado fondos de subvenciones para apoyar una variada programación artística hispana y latina en el área. Habiendo dirigido varias bandas y coros a nivel de escuela secundaria y universitario por décadas, Kuehner se siente especialmente emocionado de haber podido traer a la ciudad al prometedor cantante de ópera Mario Arévalo.

Oriundo de El Salvador, Arévalo ahora vive en Miami y visitó Hampton por un fin de semana; tiempo en el cual trabajó con estudiantes solistas de varios coros del área y, junto a estudiantes, ofreció un concierto abierto a todo el público.

“En el concierto interpretó música de Centro y Sudamérica. Música de Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, Perú, República Dominicana, México, Cuba y El Salvador,” dice Kuehner. “El comentario que escuchamos mucho fue, ‘Vaya, veo a alguien que se parece a mí cantando ópera’”.

Arévalo fue tan bien recibido en Hampton que ya está planeando un viaje de regreso en la primavera del 2024.

“El arte y la cultura es lo que une a las personas. Cuando tienes una comunidad diversa, esas son las cosas que todos aman”, dice Kuehner. “Y todo está relacionado. Como Marissa pintando los retratos sin rostro en los que puedas proyectarte. Los estudiantes pueden decir, ‘Sí, puedo crear arte. Puedo hacer música. Puedo ganarme la vida como artista’”.

Translated by Pia Hovenga / Traducido por Pía Hovenga