About an hour’s drive southwest of Chicago, nestled in the Illinois River basin, is a ten-acre oasis called Bray Grove Farm.

The property stands out amongst the surrounding monocrop fields of “big ag” farms. Half of it is a wild meadow where many species of wildlife congregate; the other half is home to a young fruit tree grove, vineyard, and row crops — including squash, arugula, ochre, and traditional Japanese vegetables such as edamame and shiso — that are planted amongst wild vegetation.

After spending most of her life in Chicago, artist Joanne Aono purchased the farm with her husband eleven years ago. The couple had long been involved in environmental and animal rights advocacy, but desired to become more “hands-on” with their values. So, they decided to rescue a horse.

After researching, they found a horse living on a farm that was going to be euthanized. But instead of only buying the horse, “we ended up buying that farm,” Aono said.

Since then, Aono has helped build a farm that is “extremely unique” — even by the standards of most small organic farms. So gentle on the earth, it employs a pair of Belgian draft mules to pull farming equipment instead of using a fossil fuel powered tractor. Produce is sold in a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program, and a percentage of the harvest is donated to the local food pantry.

“It’s not just a vocation, it’s a belief,” Aono said. “[Farming] is part of the lifestyle I want to live: giving to the earth, to people, to animals.”

Joanne Aono“It’s not just a vocation, it’s a belief. [Farming] is part of the lifestyle I want to live: giving to the earth, to people, to animals.”

Aono says her interest in growing food isn’t only about cultivating a relationship with the earth; she links it back to her grandparents, who were agrarian workers and immigrated to the U.S. from Japan.

“Like many immigrants coming to the United States, food was a vital part of their life and their culture,” Aono said. “That’s become part of my art, the idea that growing food is a cultural thing.”

Aono comes from a family of creatives; her identical twin sister is a prominent sculptor. She says much of her earliest work dealt with her personal history — both her Japanese American heritage and identity as a twin.

“From there, I went on to think about people’s pursuit of growing foods that become their comfort foods,” she said.

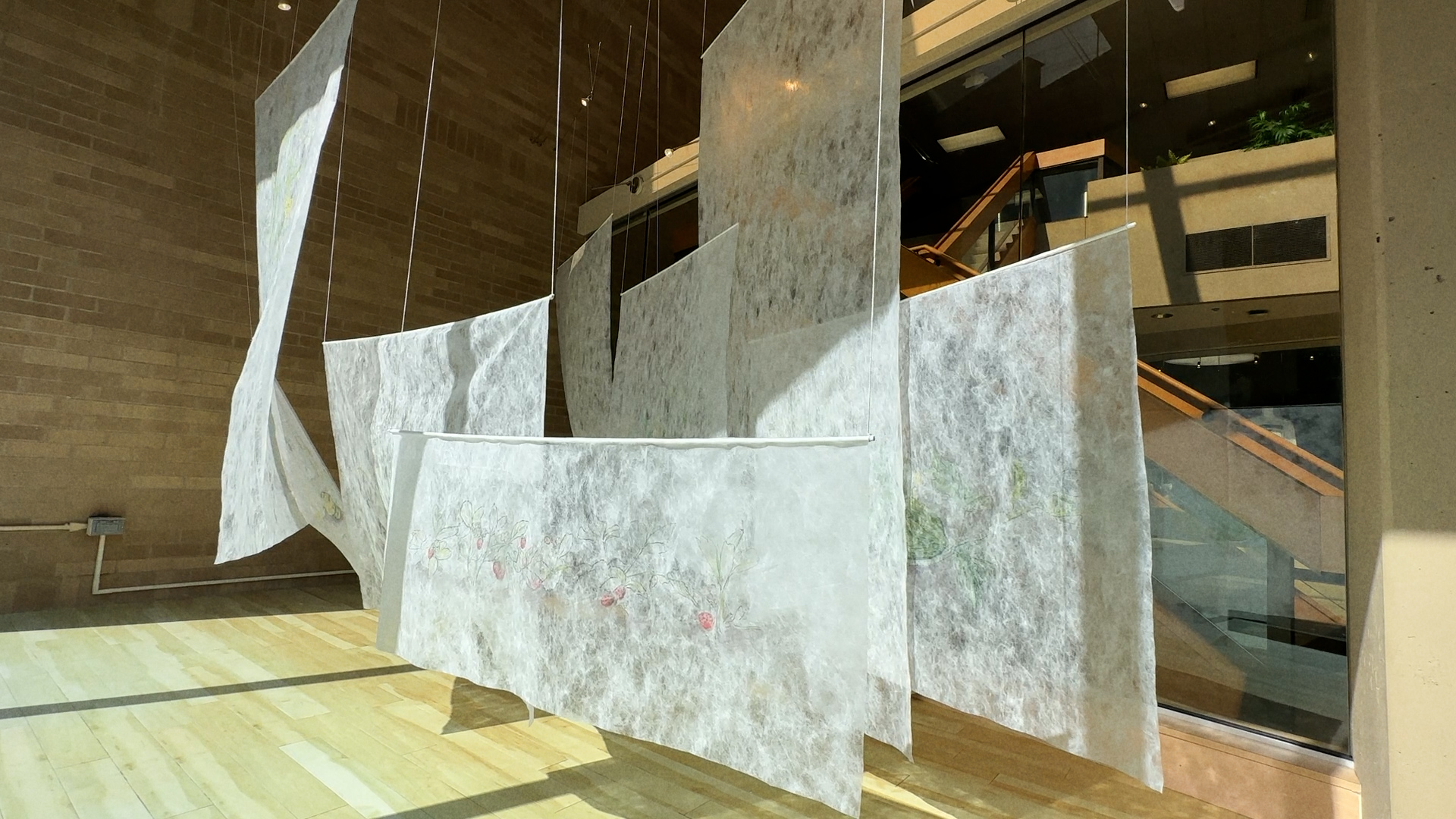

One of Aono’s most recent series of works, “Harvesting Ethnic Roots,” is a large-scale installation of gauzy agricultural cloth on which Aono has drawn comfort foods from different cultural traditions.

Other recent pieces include installations of seed art, which she describes as a collaboration with the farm’s creatures and natural elements that inevitably rearrange the original designs.

“I relate farming a lot with art because … oftentimes what you end up having isn’t anything that you planned on; [sometimes it] totally gets ruined, or sometimes it surprises you and something wonderful happens,” Aono said. “Farming is a lot of work, but so is being an artist.”

Cultivator is another extension of Aono’s inclination to help everyone thrive. Nearly a decade ago, she began inviting other artists to exhibit their art on the farm — many of whom had never installed work outside before. The property is open to the public twice a year when people come to gather, eat food, spend time with the animals, and immerse in original art.

Aono is passionate that Bray Grove is a connector—“I think it’s really important that the farm welcomes others.”