Welcome to our new series of quick, data-driven research briefs, created in partnership with I/O Research. Each brief takes a closer look at what national datasets reveal about the arts sector and what sets the Midwest apart.

This brief dives into IRS 990 data from the Exempt Organizations Business Master File (BMF), which provides basic financial and organizational information for tax-exempt nonprofits. These records reflect formally incorporated 501(c)(3) organizations—but don’t capture fiscally sponsored projects, unregistered groups, or informal collectives.

In other words, what you’ll see here is just one part of the picture. But it offers a valuable look at how the region’s nonprofit arts organizations are distributed, how they’re faring financially, and what patterns shape their development.

Let’s explore the data to understand where Midwest arts organizations are located, how old they are, what they own, and how they’re recovering from pandemic-era disruptions.

Explore the Data Set on Arts Analytics

Play with the Business Master File findings on I/O’s new platform that lets users experience the art of data.

Learn MoreDifferent states have different strengths in their arts sectors

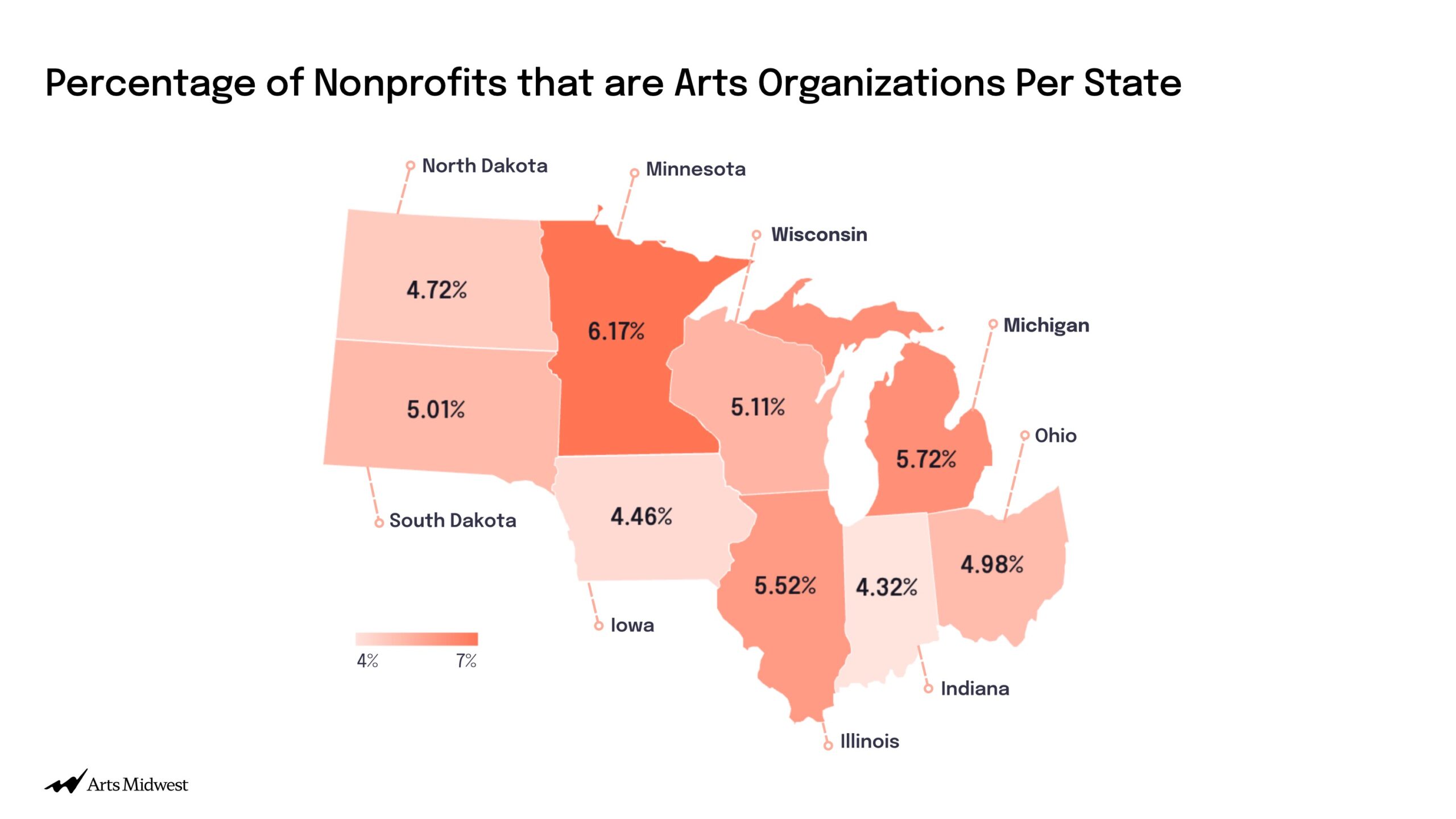

From theaters to museums to cultural festivals, arts nonprofits fill a wide range of roles across the Midwest. But some states support denser cultural ecosystems than others.

Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois lead the region, with over 5% of their registered nonprofits focused on the arts. Indiana, by contrast, has a smaller proportion—just 4.3%—suggesting a less saturated but possibly more concentrated arts landscape.

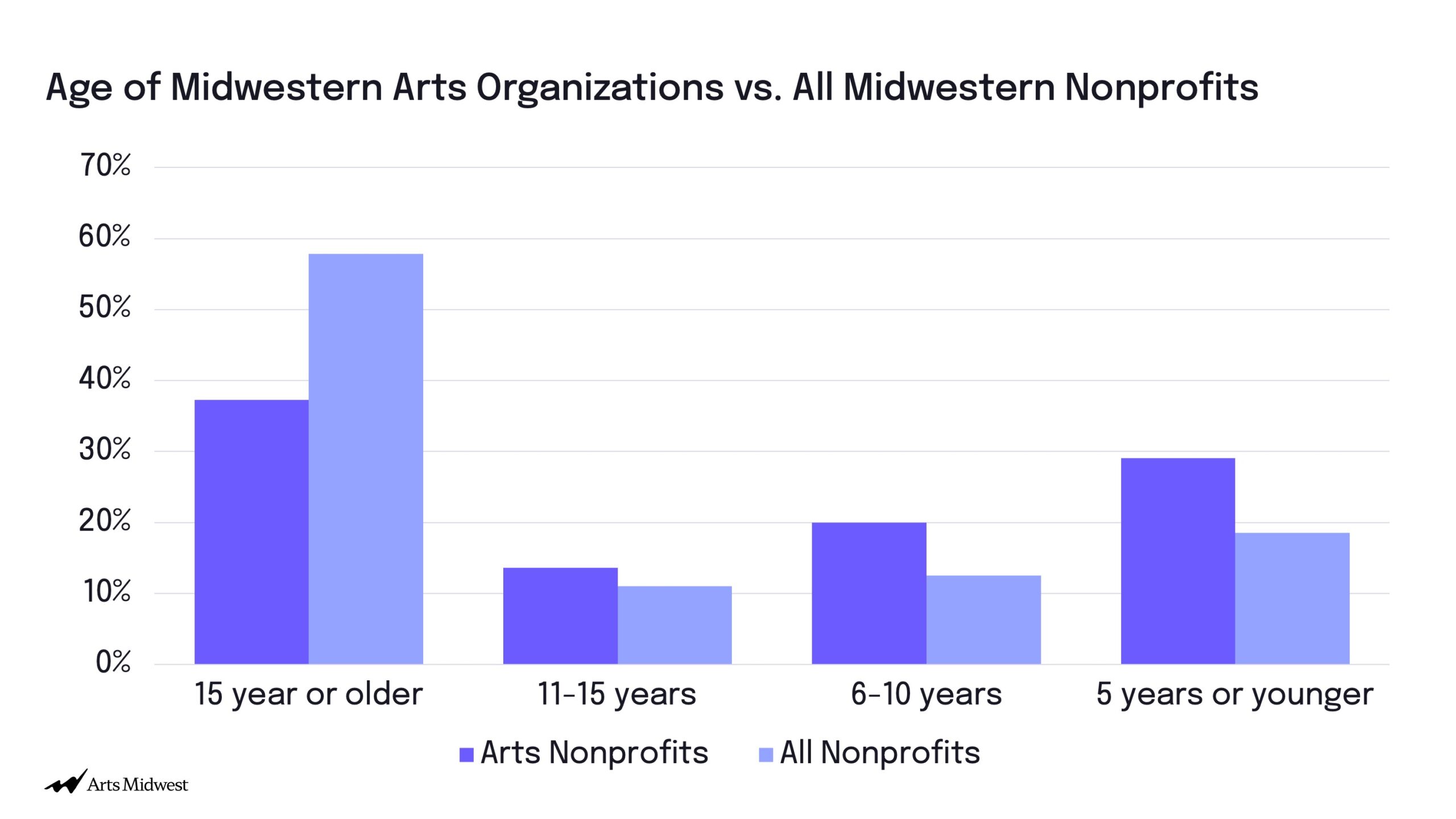

Midwest arts orgs are younger—and turn over more often

Most nonprofit arts organizations are relatively young, especially compared to other nonprofit sectors. In the Midwest, the average arts nonprofit is about 16 years old—far younger than the average Midwest nonprofit overall (45 years).

About 29% of Midwest arts organizations are just five years old or younger. That’s a sign of high turnover—but also of continuous renewal. This youthfulness may reflect post-recession shifts, lower startup barriers in the arts, differences in business models, or even new models of community arts engagement taking shape.

Older arts organizations tend to be more financially stable

Here’s a clear pattern: the longer an arts organization survives, the more assets it’s likely to accumulate. While many arts nonprofits across the U.S. report having few or no assets—especially newer ones—those that make it to 15+ years are significantly more likely to have financial reserves.

In both the Midwest and elsewhere, older organizations are the financial anchors of the sector. But in the Midwest, even younger organizations are doing slightly better: among groups five years old or younger, Midwest organizations report higher average asset values than their peers in other regions.

This suggests the Midwest may offer a more supportive environment for new organizations to get a foothold—through affordable space, lower operating costs, or regional support systems.

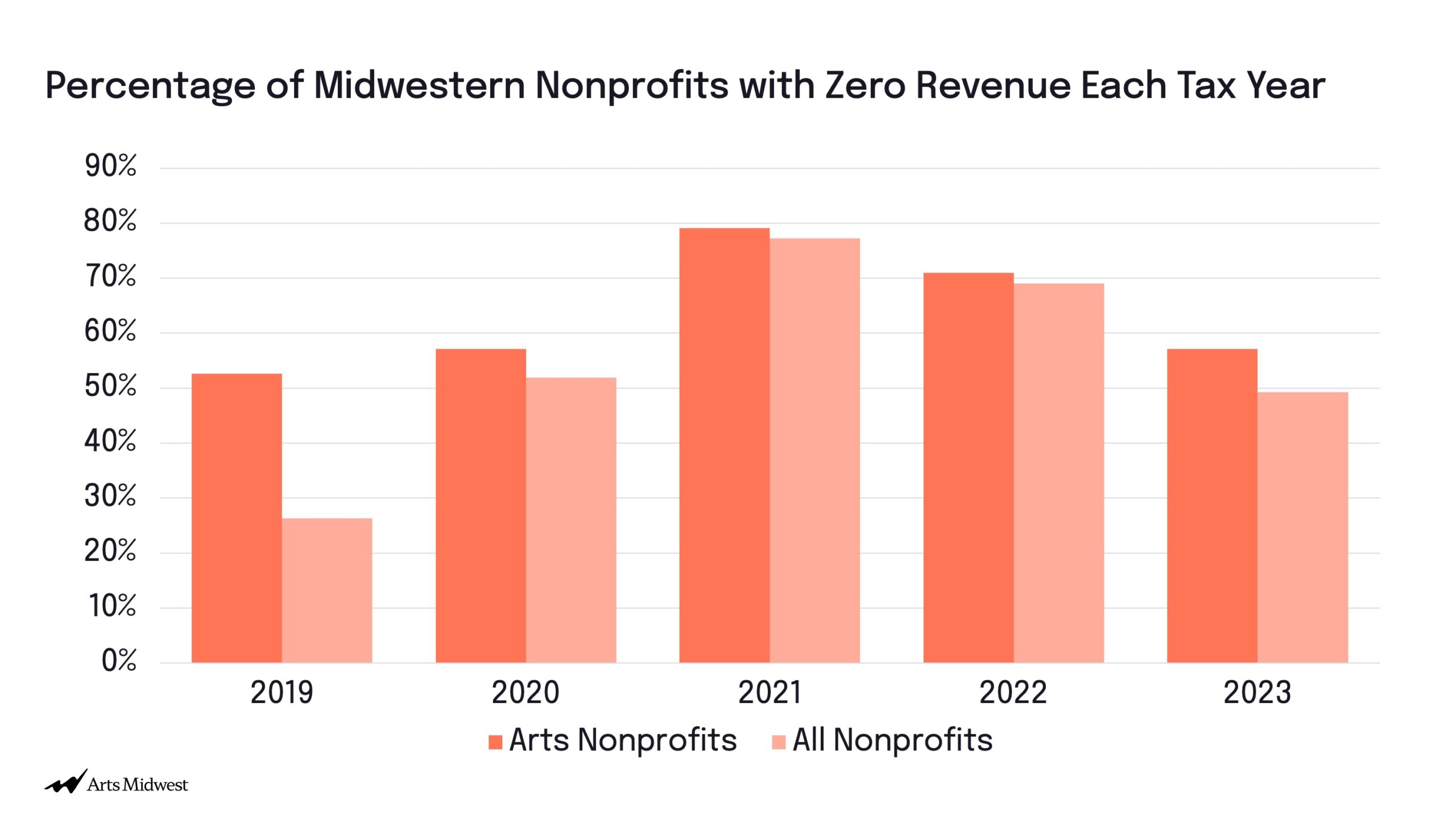

Financial recovery remains uneven post-COVID

The pandemic left a deep financial scar on the arts—and many nonprofits are still struggling to rebound.

In 2021, nearly 80% of Midwest arts nonprofits reported zero revenue on their tax filings, a sharp jump from pre-pandemic years. That rate declined in 2022 and 2023, but more than half of the region’s arts nonprofits were still reporting no revenue as of the most recent tax year.

While some of this may reflect delayed filings or accounting lags, it also points to a troubling reality: the sector remains financially fragile.

Many Midwest arts orgs operate in more economically challenged and rural areas

Compared to arts nonprofits in other parts of the country, Midwest organizations are more likely to be based in smaller metros or rural regions. Roughly 22% are located outside major metropolitan areas—higher than the national average.

They’re also more likely to operate in areas with higher unemployment and lower income levels. That means these organizations are providing cultural value in places that often lack access—while also navigating more limited donor pools and public funding.

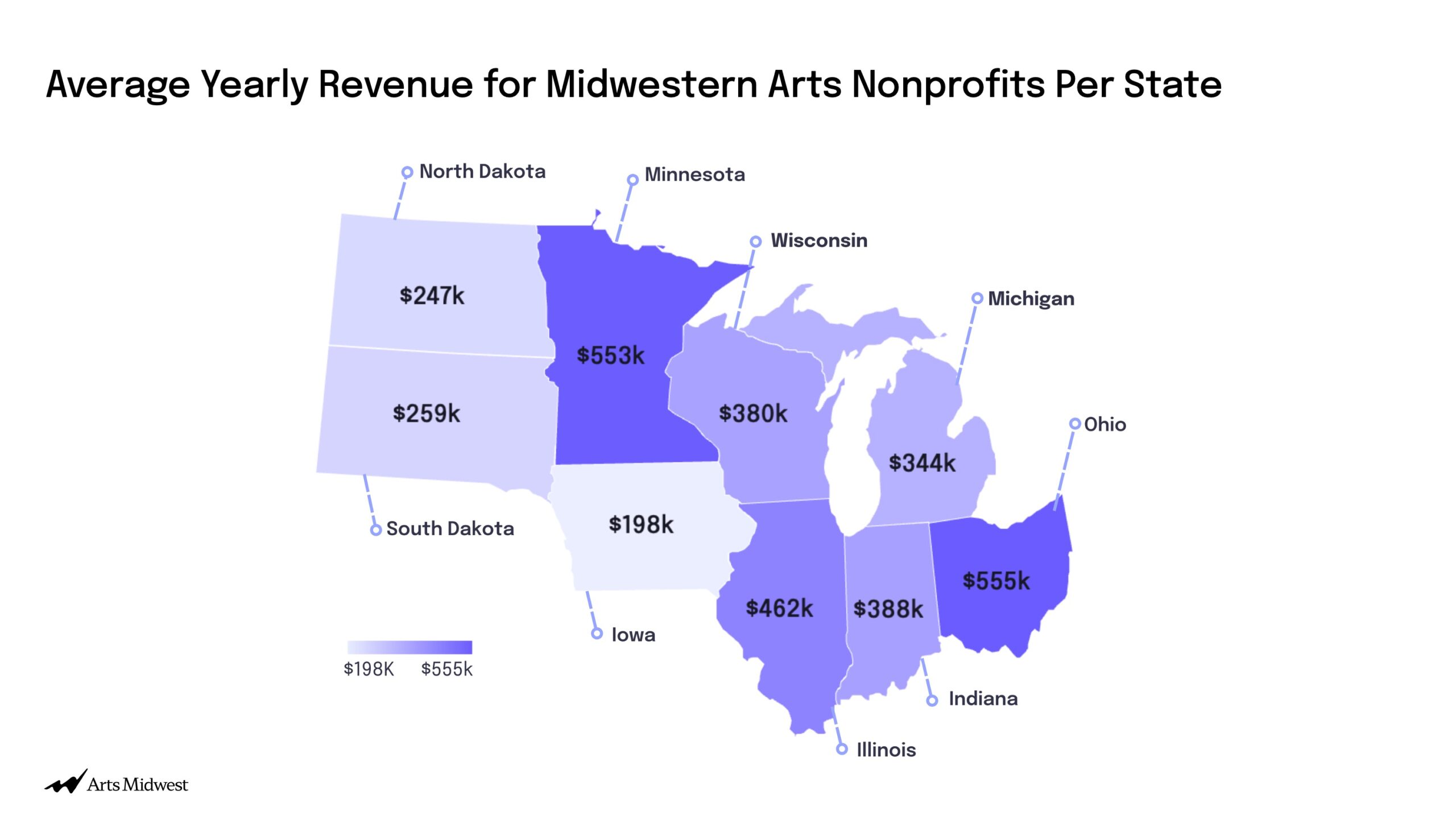

Geography shapes both access and stability

Midwest arts organizations are not only fewer in number in some states—they also operate on very different financial terms. States like Ohio and Minnesota lead the region in average revenue per organization, while others, including Iowa and North Dakota, fall well below.

These geographic disparities matter. Where an organization is based affects what it can raise, who it can reach, and how it can grow.

Conclusion: A region of renewal—and risk

The Midwest offers a distinct environment for emerging arts organizations—one where new groups can gain traction more easily, thanks to lower costs and accessible infrastructure. But these same organizations often face serious financial precarity, especially in the wake of COVID-19.

While older institutions tend to be more stable, many communities rely on younger, smaller groups to fill key cultural roles. Supporting this infrastructure—through policy, philanthropy, and public awareness—is essential to building a more resilient and vibrant arts ecosystem.

The takeaway?

If we want a thriving future for the arts in the Midwest, we need to invest not just in legacy institutions, but in the flexible, fast-moving organizations that are growing up all around them.