The Arab world has long contributed to the arts through its painting, poetry, and music, however, in recent decades those of Arab and Muslim backgrounds have endured misrepresentative depictions through mainstream media which has denigrated their rich cultures. In cases of artists and poets like Rumi who have broken through to the West, their Islamic identity often goes ignored or erased, leaving their cultural influences rendered insignificant.

The founders behind Midwestern arts organizations Mizna (Minnesota) and Masrah Cleveland Al-Arabi (Ohio) reject this erasure of Arab culture and tradition in artistry and implore the artists they work with to come as their full selves when sharing their works. Both arts initiatives—one for literary and film and the other for theatrical performances—aim to share the nuanced perspectives and experiences of artists from the SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) region with Arab and non-Arab audiences alike.

Artist-Led, Community-Built

Mizna was founded by Kathryn Haddad and Saleh Abudayyeh who were Twin Cities locals and active in organizations and advocacy groups that helped promote a representative arts scene. As volunteers with the Minnesota chapter of the Arab American Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) , they put together a newsletter for the local community. This caught the attention of ADC’s national leaders and their work was amplified to a broader audience.

“They were just really surprised by the volume of submissions they got, including from people who even at the time were quite well known outside of Arab literary circles,” said Lana Barkawi, Executive and Artistic Director of Mizna.

Mizna published its first issue Mizna: Prose, Poetry, and Art Exploring Arab America in 1999 and in 2003 launched the Twin Cities Arab Film Festival. Both of their flagship programs were the first of their kind and created platforms for Arab artists to engage with the diaspora.

Barkawi recalled her first experience with the organization; moved by the sense of community that she found in an artistic space. “I hear people say this a lot when they come to visit events for the first time—that it was a community that they didn’t realize they were missing from their lives,” she said. “This low-level sort of fever that you have where you don’t quite realize you’re sick when you’re kind of disconnected from community.”

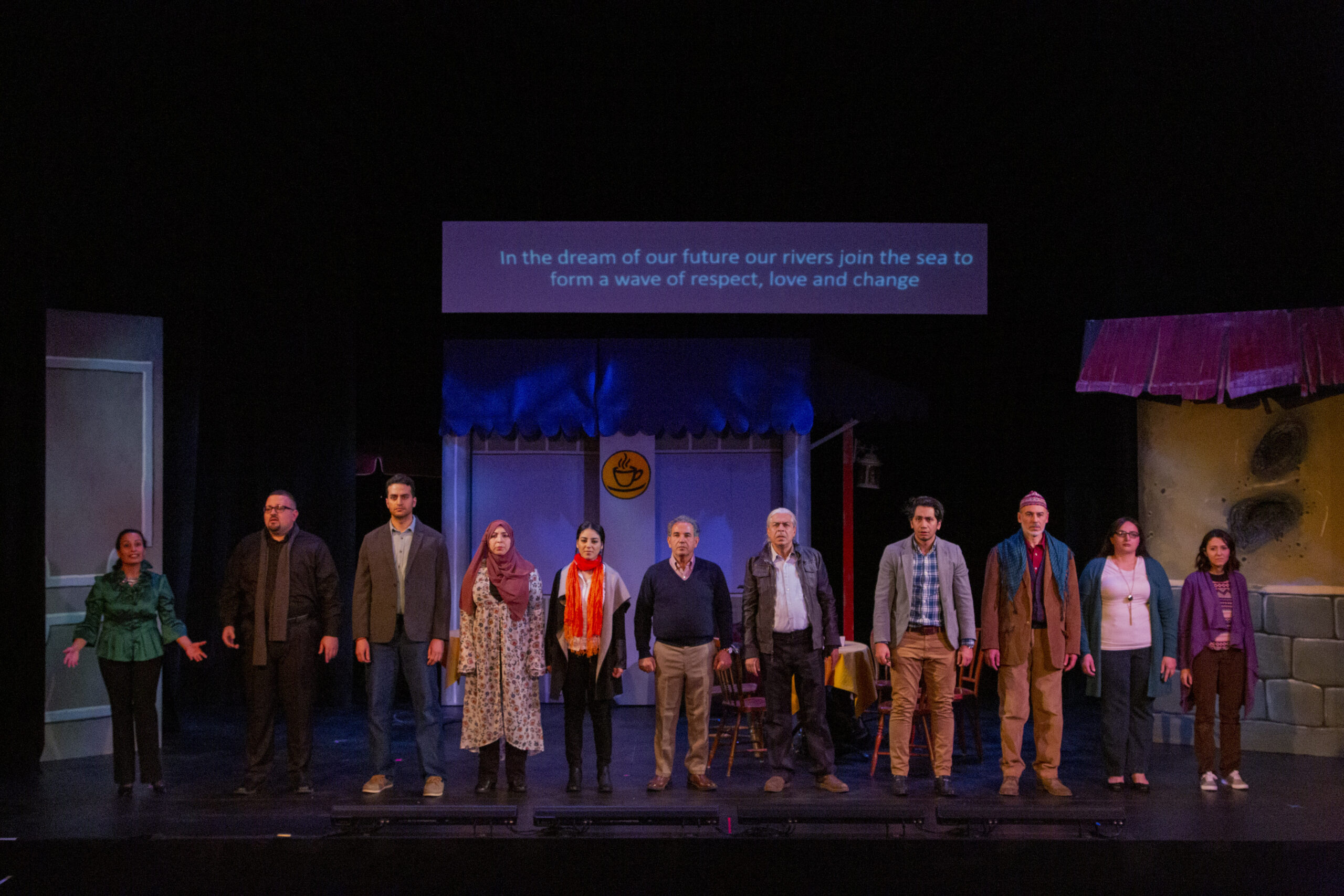

Similar to Mizna, Masrah Cleveland Al-Arabi aims to give a platform to Arab American artists; however, the idea for Masrah was born out of a broader vision of culturally inclusive work in theater.

Raymond Bobgan, the executive artistic director of the Cleveland Public Theater (CPT) and a writer-director, has launched several of CPT’s initiatives including cultural programming through Masrah, and Teatro Publico de Cleveland 10 years ago with the goal of setting up a theatre company for Latino artists. Much of the work done at CPT is artist-led often resulting in original plays.

“Cleveland Public Theater has been an outlier in the national theater field. One because we do work that is pretty radical. We predominantly do new work, brand new plays. Not new like it was just on Broadway, new like we’re the first theater to do it,” Bobgan stated.

CPT is led by a majority BIPOC board, reflecting the diversity of its surrounding neighborhoods which are made up of largely Black and Latino communities. Coming from an Armenian background, Bobgan was curious as to whether he could create another theatre company with a focus on the Southwest Asian and North African regions which encompasses many different cultures, largely in the Arab and Muslim worlds. There was a significant population of Arabs in northeast Cleveland in an area known as ‘Little Arabia’ that this work could service, he thought.

To better tackle this idea, he approached community members and held workshops with Arab artists. Though this process helped Bobgan gain a sense of the stories Arab artists wanted to share on stage, he quickly learned that these artists had high regard for their respective cultures, and to operate under such a wide umbrella would not feel right. This helped hone Masrah’s focus on Arabic plays.

After three years of exploring and working to build an artistic community, Masrah Cleveland Al-Arabi was founded in July 2018 and had its first production that fall.

Mizna and Masrah share a sense of specificity in their approach, not only toward Arab artists, but toward an Arab audience as well.

“It was sort of work for our community, by our community. So, like thinking about the audience being other SWANA folks foremost and not that it was exclusive, but there is an important distinction when you’re not catering to a non-Arab or non-Muslim audience,” Barkawi explained.

LANA BARKAWI, EXECUTIVE AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF MIZNA“I hear people say this a lot when they come to visit events for the first time—that it was a community that they didn’t realize they were missing from their lives. This low-level sort of fever that you have where you don’t quite realize you’re sick when you’re kind of disconnected from community.”

Significant Spaces

Omar Kurdi was one of the founding artists brought into the fold when developing Masrah. The theatre company was launched just a month after Kurdi’s father passed.

“Having that space [Masrah] was very healing. It also felt very nurturing,” he said. “It gave me an opportunity to also think outside the box because sometimes I feel like us as humans, it’s so easy to just dwell over our own problems and think that our experiences are the only experiences happening.”

With the launch of Masrah, many Arab artists who previously operated independently or in smaller settings were now able to share a larger platform and bring their works to life.

“Meeting so many different artists from so many other countries and different faiths at the same time literally opened my eyes and it allowed me to dive into other people’s cultures,” Kurdi said.

As a Jordanian, Kurdi was able to interact with artists from across the Arab world, an experience he credits to Masrah. “I think that that’s the beauty of it is that we come to realize that our differences are actually more of similarities, and I don’t think we would’ve realized that outside of Masrah’s space.”

Masrah’s ability to highlight the diversity within the Arab community not only through nationalities but also through different religions is well-recognized. Those from Sunni and Shia backgrounds, Christians, and Druze have all worked together to share stories highlighting the Arab American experience in the Arabic language.

“I think that has some impact on how the community starts thinking of itself,” he said.

For Lamia Abukhadra, Mizna’s Art and Communications Director, Mizna was a platform to give the global Arab community a new method of exchanging ideas and furthering the conversation.

“I think it’s just critical for organizations to bring people together to converse on the social realities that are affecting our communities, whether we are in [the] diaspora or living in the region, because it’s in this way that we build aesthetic languages together. We create sort of new forms of community,” she said.

Mizna’s film series is one approach to broadening the conversation, according to Abukhadra, as it aims to tackle topics around surveillance and regional conflicts. Their process of open calls to filmmakers for submissions often lends itself to organic conversations after screenings. Mizna has screened the works of over 400 artists to roughly 10,000 people, sharing works from around the globe with a diasporic community. The literary journal has also widened its reach globally with new distribution in Europe and the SWANA region.

Much of the conversations that these organizations facilitate, with their artists and audiences alike, center on identity and broadening the idea of what it means to be Arab.

Multiplicity in Identity and Ideas

Cultures such as Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian have been synonymous with what it means to be Arab in mainstream depictions of the region. Mizna has worked to expand that definition to include North African cultures and black Arabs from these countries, and nations like Sudan that have large black Arab populations.

Mizna is set to launch their Black SWANA issue in February of 2023, guest-edited by Safia Elhillo and produced by “an all-black takeover team,” who explore the black SWANA identity and experience.

“We don’t want to simplify identities. It’s really important to have a space for the diversity and multiplicity that the region holds,” Barkawi said of Mizna’s approach to capturing the Arab experience.

Mizna released their Queer and Trans Voices issue in the summer of 2020 where they platformed the works of queer SWANA artists. “Sometimes there’s a discomfort within the community about that, even though this is something happening in the region. It’s not something that we’ve invented, but there’s like artists working all over the region and in the diaspora who are queer and Arab and Muslim,” Barkawi said.

In Kurdi’s eyes, a significant move will be to fully embrace queer Arab Americans in northeast Ohio. “Their stories matter,” he said.

The lesson that both organizations impart to other organizers is to empower the artists and not be afraid to let them lead. Whether it’s Mizna’s Black SWANA takeover issue or Masrah’s artist-led programming, there is a lot of confidence placed in the hands of creatives.

“We’re not very hierarchical and I think this fosters a lot of dialogue, both within the organization and whenever we are collaborating with artists or editors or filmmakers or whoever it may be,” Abukhadra said of Mizna’s operational approach. “It creates a space where we’re exchanging ways in which we should be working as an organization and also how we should be producing work. There’s quite a lot of listening happening.”

This is a two-part story on how cultural spaces explore identity and belonging through creative expression, written by Abdi Mohamed. Complete your reading of the series with ‘A Second Home: Fanana Banana and Soomaal House.’