No matter the context, Rhonda Greene is an educator and a gracious leader. She entered the dance world at 12-years-old during an isolating and often demeaning time, where African dance was overlooked and underfunded. As she matured through her practice and began to understand her place in the world, she grew deeper in her knowledge of African dance. Now, she emphasizes an ethos that thinks, moves and connects beyond the bounds of Westernized cultural standards.

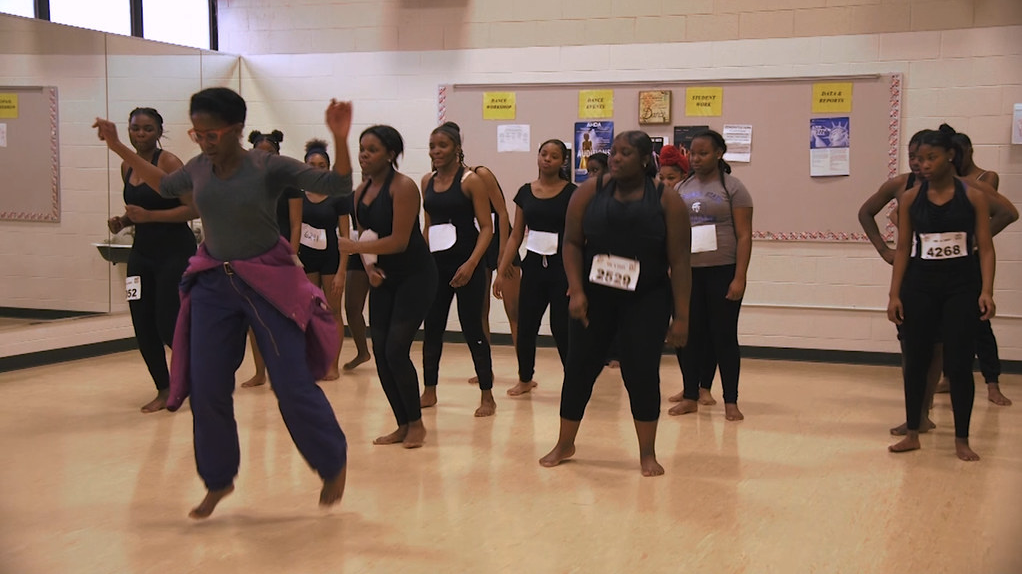

For Greene, African dance is not a hobby or an occasional class, it’s an expressive, anthropological tradition that brings and holds us together. Located in Detroit, Heritage Works is moving intentionally and collectively to reclaim and affirm Blackness in the Blackest city in America.

What is your first memory of attending a dance class?

Rhonda Greene: I remember thinking dance class wasn’t for me. That’s all I can say. Because my body couldn’t do and didn’t look like the requirement. I grew up north of the city and the narrative around beauty was very different. When I moved to Atlanta, GA, I think I was old enough to understand different senses of beauty. Then, you know, I think I grew more into the pride of it. African dance was the closest thing I could get to the freedom I was longing for. So I would say the first time I went to a dance class that I really loved, was when I was 12. And it was African dance.

Was it an instant click where you felt like you needed to incorporate dance into your life, or was it an eventual addition?

My sister used to take me. She was away at college at that time, so I only went to African dance class when she came home and took me to Ngoma Za Amen Ra classes. It was more like a delicacy then, a dessert. I had a few classes here and there, you know, after long stretches. It was my junior year in college when I started dancing Guinean and Ghanaian dance consistently. I then went to grad school at Brown University in Rhode Island. They had an African dance class on campus and I think I’ve danced ever since then.

What drew you to dance?

Drumming always seems poetic to me. I think when I understood that there was a language to it, it made sense, because I knew there was something intelligent going on there. There’s a lot of technique and there’s a lot of tradition and rhythm and language that goes back far beyond what we know. I knew that something was going on, it spoke to me. I just didn’t have the words yet to talk about it.

African dance is pretty central to your identity now, was it always that way?

For a long time it wasn’t anything you bragged about. You might brag about ballet and modern, but you didn’t brag about African dance. Back in the day, the prevailing images [of Africa] were Tarzan images and starving children. African dance didn’t seem like something to aspire to or pursue in school. My mother started traveling to Africa and bringing back beautiful sculptures and stories that changed my thinking. I knew African dance spoke to something deep inside me. I had to put that together. It’s like the puzzle I keep trying to put together. It’s deep and wide, it doesn’t stop.

How do you go from being introduced to African dance and feeling like you don’t identify with it completely to leading Heritage Works?

West African dances often have restorative or healing properties. They put you in touch with community, just the fact you’re dancing to someone who’s drumming, that’s a conversation. My son Kamaal’s counselor called and told me he was teaching African dance at recess and if enough kids were interested they could perform in the talent show, but they needed a parent sponsor. So I started as the parent sponsor at his school and the need developed from there. I realized that there were kids besides mine that needed this resource, not just in February, but all year long. We started providing after-school programs and then our young people wanted to perform, which led to an ensemble. It just kind of grew organically. A lot of it was just following the need. Following the children, following the needs of families, of schools, and finally, community.

What has African dance taught you about art as a whole?

Art isn’t something that sits on the wall. It is the center of community, and it generates community, a community generates it. Art can restore and heal our community, and be restored by our communities.

How has the pandemic affected the number of students you can accommodate?

I think the first year our numbers dropped to 50 students and now we have approximately 10 students. Typically, we provide short choreographic residencies or yearlong classes —two classes per school for five schools, serving approximately 300 students. We’re nowhere near that. Some teaching artists are concerned about teaching in person. We also wrestle with keeping students online for long times and keeping them engaged virtually. The beauty of virtual classes is that we can hire dancers from all over the world. Right now, our young people are working with teaching artists and tradition bearers in Detroit, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Dakar, Senegal.

A lot of people think of the arts in general as frivolous, why is dance and movement so important to you?

It is central to the community and it happens at the center of the community. And everybody has to participate. It’s really about building community. That’s very different from the western sense of art that you purchase, that you hang on your wall. It makes you feel good.

Why Detroit?

I love Detroit. It is the blackest city per capita in the country. A lot of the traditions that sustain African Americans, aren’t acknowledged. We have to do underground, right? Because our major institutions have white norms.

For me, I think it’s been about surfacing and helping people understand that there’s a reason you love the rhythm or you love the way the food tastes and it has a lot to do with your heritage. “Heritage” shares the same root word as “heir.” So it has to deal with the things we pass from one generation to another and we were doing a lot of stuff unintentionally because of the dispersion of African people and the Middle Passage. But how do we get back in the driver’s seat? What should we intentionally pass on from one generation to another? That is really important to me.

What is your hope for Heritage Works moving forward?

I feel like there’s an opening of the door right now. For so long people saw us and they marginalized the work we did. I hope that our work can be seen as central, especially to a city that is primarily of African ancestry. It is essential. It should not be a one-semester thing. It should be the aesthetic here. It is the lens through which we look at the world. I hope to grow our staff, grow our purpose, and grow our resources so that we can have what we need to thrive and do the work more meaningfully and on a larger scale.

RHONDA GREENEArt isn’t something that sits on the wall.

It is the center of community, and it generates community,

a community generates it.

Heritage Works is a United States Regional Arts Resilience Fund recipient. Check out our History for more information about this program. Thanks to the Mellon Foundation and an anonymous donor for their support of Heritage Works and other Midwestern arts organizations.