An hour southwest of Columbus, in the township of Oldtown, Ohio, construction crews are hard at work on the state’s newest state park. In the 1700s, Oldtown was a hub of Shawnee life in Ohio, which makes it the perfect site for the new Great Council State Park. Set to open in 2024, Great Council will have a 12,000-foot facility with educational exhibits and an art gallery designed to honor the Indigenous peoples expelled from Ohio two centuries ago during America’s violent westward expansion.

While the Shawnee people’s ancestral land is in Ohio, today, the tribe is primarily based in Oklahoma. Tribal leaders were consulted about Great Council to ensure the interpretive center was created with respect for the Shawnee and other Indigenous peoples from Ohio at the center. That’s how Talon Silverhorn first got involved. What began with providing historical context and fact-checking to ensure the educational information was culturally appropriate has turned into Silverhorn moving to Ohio to develop and run the interpretive center full-time.

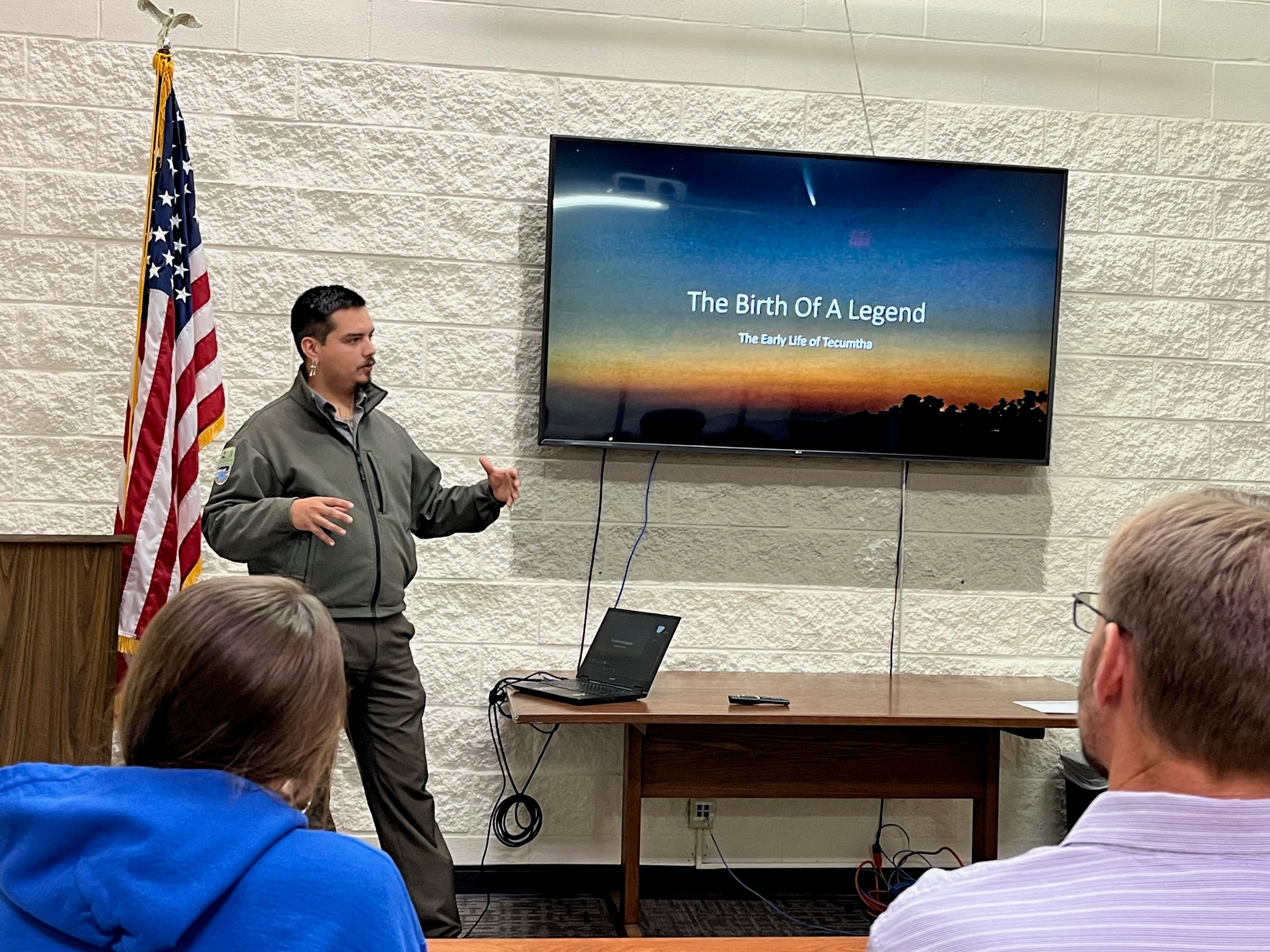

TALON SILVERHORN, CULTURAL PROGRAMS MANAGER, OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES“Seeing history in action can be cool and impactful, so we have a specific goal to de-militarize living history by talking about family life and daily routines and the people behind the scenes…”

“A lot of the content I’ve developed for Great Council has been more about helping people connect with the community and seeing the community in an even light,” Silverhorn says. “You’ll learn about our family and relationships, our home life, seasonal living, [and] our relationship to natural resources not in a romanticized way but in a more traditional scientific way.”

“Not necessarily a Western science but how we in our traditional science view our environment and experiments conducted over the last 23,000 years,” Silverhorn adds. “Our relationship with the environment that people see as this very well-oiled machine only exists because of millennia of trial and error and building a relationship with the world around us.”

A Living History

One of Silverhorn’s main goals for the space is to lead visitors away from popular stereotypes and romanticized legends. One of his challenges is balancing educating non-Indigenous visitors about the Native peoples who have historically called Ohio home and honoring the Shawnee and other Indigenous people who may be visiting themselves.

“That’s a tricky one,” Silverhorn says. “For example, there’s been a continuous push to talk about more well-known characters like Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton, but as a Shawnee person, I’m sick of hearing about these people. We want to talk about people who don’t get the spotlight as much and the community in general.”

Focusing on the lives of everyday Indigenous peoples is a mission close to Silverhorn’s heart. For years, he’s run a consulting company with his wife, and together, they help historic sites develop their interpretive programs in a respectful and culturally responsive way. They’ve worked with the Frontier Culture Museum and Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, the Fort Pitt Museum in Pennsylvania, and more.

“The public has sort of lost its faith in living history as a serious form of education because it’s become this goofy, stereotypical thing. When you think reenactments, you think of guys running around in the local park pitching tents and shooting fake guns at each other,” Silverhorn explains. “Seeing history in action can be cool and impactful, so we have a specific goal to de-militarize living history by talking about family life and daily routines and the people behind the scenes and the 99% of the population who were never warriors or fighters of any kind who were just trying to make their way in the world.”

TALON SILVERHORN“I want Shawnee and other Native people who have been removed from Ohio to be able to identify Great Council as a place they want to be and be a gateway in reverse. I want people to look from Oklahoma to Ohio and see this as an opportunity to connect with our tribal communities no longer living in Ohio.”

A Place for Community

That sense of everyday life begins with the construction of the educational center itself. Rather than being modeled after a fort or other foreboding militaristic structure, the design is based on a longhouse, a traditional gathering space typically at the center of the community. Religious ceremonies, voting, political discourse, and anything that brings the community together take place at the longhouse.

“The intentional design of the space as a longhouse is meant to do exactly that—to bring people together and open conversation,” Silverhorn says. “It’s a symbol of reconnecting these communities that have been diaspora’ed over the last 200 years in Ohio and Oklahoma.”

The basement art gallery further reinforces this connection. As a 4,000-square-foot rotating gallery, the space will have shows featuring historical art and contemporary Indigenous artists’ works. The first show will be a photo exhibit curated by the Ohio History Connection that will showcase large color portraits of tribal citizens in Oklahoma, including the three federally recognized Shawnee tribes, the Shawnee, the Eastern Shawnee, and the Absentee Shawnee, in addition to the Seneca Cayuga, Wyandotte, Delaware, Miami, and other peoples removed from Ohio.

“The gallery’s theme is exploring what it means to be part of these communities,” says Silverhorn. “We’ll be exploring federal recognition and what that means, community and religious participation, diversity within the community, and dispelling some of the more common myths about American Indian people. For example, we don’t define ourselves by ethnicity but by our community and political relationships.”

A Connected Approach

All three federally recognized Shawnee tribes were involved in the process from the beginning, and every part of the design and development of the space should feel familiar to Shawnee people. Silverhorn has worked to make the space feel like home, from the color palettes to the fact that the Shawnee language comes first and is then translated to English, along with a full-scale traditional dwelling inside the longhouse.

“I want Shawnee and other Native people who have been removed from Ohio to be able to identify Great Council as a place they want to be and be a gateway in reverse. I want people to look from Oklahoma to Ohio and see this as an opportunity to connect with our tribal communities no longer living in Ohio,” Silverhorn says. “I think a Shawnee audience coming to the site with their family will experience seeing their history and stories represented in a way that’s rare to see outside of us doing it entirely ourselves… [Ohio] has had such a long history of mythologizing us and romanticizing us, or demonizing us, so it’s important to see this fair, accurate representation of what our historical community looks like and what our modern community looks like as well.”

Ensuring that the story of modern Shawnee life is shown in the museum has been the number one thing tribal partners in the project are interested in, Silverhorn notes.

While no specific open date has been officially announced as of this writing, construction is well underway, and Great Council is set to open in spring 2024.