Creating accessible programs and offerings is about more than reaching a wider, more diverse audience. It’s a chance for your organization to consider what people need so that you can serve them in the best, most universally accessible way. How an organization approaches accessibility makes all the difference. By simply taking a more holistic approach to accessibility, your organization can take huge strides toward building a culture of understanding around inclusive, accessible programs and offerings.

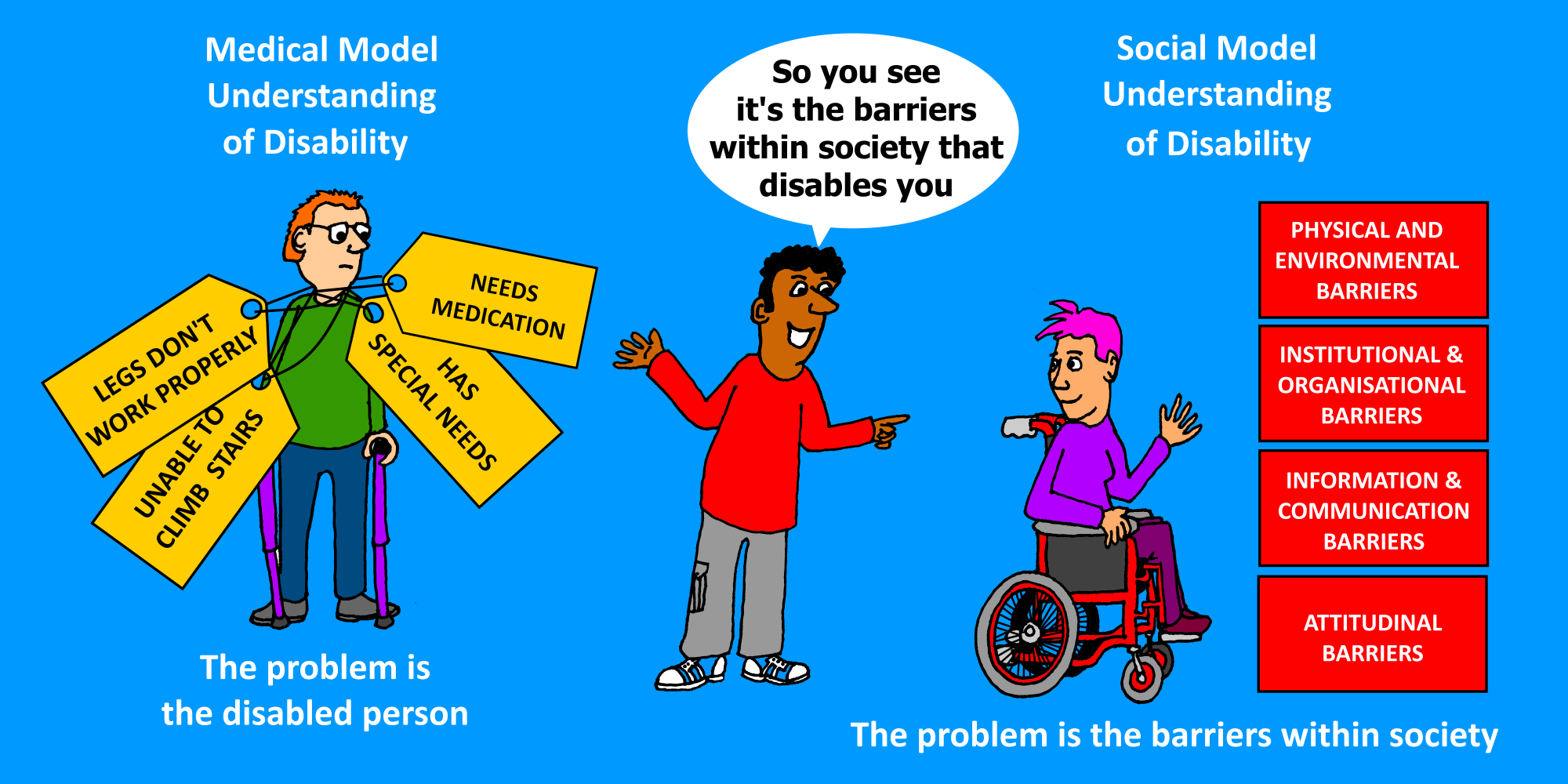

Please note in this article the phrase “disabled people” is used instead of “person with a disability.” This phrasing aligns with the Social Model of Disability understanding that people are disabled by environmental and societal barriers.

Moving Beyond a Medical Model of Disability

At Disability Arts Online, an organization led by disabled people set up to advance disability arts and culture, we work every day to combat the Medical Model Understanding of disability and encourage others to embrace the Social Model Understanding.

Societies the world over have long defined disabled people by their impairments and conditions. As a result of fear and prejudice, disabled people have found themselves scapegoated by authorities, often spending lives in poverty, or locked away in institutions.

Exclusion from society has meant that disabled people were made invisible and this, in turn, has further ingrained their separation from the rest of society. This has led to disabled people often being seen as a homogeneous group and identified collectively as ‘the disabled.’

Justification for the ill-treatment of disabled people is often supported by a Medical Model approach to ‘disability’ that focuses on the individual. It defines people by what they cannot do, or by perceived limitations, rather than by the individual’s capacity to adapt. Rather than understanding that the restrictions disabled people live with are created by society, the medical model approach defines disability as a problem that needs curing or solving, even when it is obvious that medical science cannot effect change for the better. This often leads to situations where disabled people feel trapped or blamed for their differences and that their voices are not listened to.

This Medical Model understanding of disability attaches labels to disabled people and defines people by their impairments. It focuses on the things that disabled people can’t do, such as not being able to climb stairs, work beyond certain periods without a break, access the written word, or hear spoken language. In so doing the Medical Model bias reinforces the belief that disabled people have little value and are a burden on society.

In the 1970s, disabled activists in the US and the UK began to challenge the perception of disabled people as unfortunate, abnormal, and unable to contribute to the economic good of the community. Disabled people began to express that these ideas contribute to their oppression and are the consequence of fear, pity, and discrimination. 50 years on, disabled people are still fighting for recognition and understanding of disability as a human rights issue.

Adopting a Social Model Understanding of Disability

The Social Model understanding of disability first emerged within communities of disabled people in the UK in the 1980s. It was developed to counteract the negative perceptions of disability that were brought about by the Medical Model understanding. Disabled activists and academics began questioning society’s attitudes. They identified the barriers that prevent a disabled person from playing a full and active part in society. They understood disability as an idea created by society and as such being a political issue. The Social Model challenges the idea that the cause of ‘disability’ is located within the individual.

The Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People (GMCDP), a disabled-led organization in the UK, clearly explains the core principle behind the Social Model understanding:

THE GREATER MANCHESTER COALITION OF DISABLED PEOPLEThere is a radical difference between impairment and disability. Impairment is an individual’s physical, sensory, or cognitive difference such as being blind, having a physical condition, or a learning difficulty. Disability is the name for the social consequence of having an impairment. Where people with impairments are disabled by society, disability is, therefore, a social construct that can be changed or removed.

Working Towards an Inclusive Society

In a nutshell, the Social Model defines disability as the lived experience of barriers. This understanding has transformed the lives of many disabled people. The Social Model perspective turns disability on its head and challenges the barriers that exclude disabled people. For several decades, disabled people have worked in different ways to achieve inclusion in all parts of society.

A key point of the Social Model understanding is that people are not to blame for their impairments. The lack of access is the fault of a society that refuses to acknowledge difference as an aspect of the human condition. Those differences should be expected and respected as an ordinary part of life.

Looking at Disability from an Artist’s Perspective

For many disabled people, understanding the Social Model perspective has not only enriched their lives but has literally been a lifesaver. In adopting the Social Model understanding of disability, many disabled artists have taken this newfound way of thinking and shared it with their communities.

To quote a few individuals directly, disabled artist Michelle Baharier, told Disability Arts Online she felt the Social Model understanding allowed her to identify and understand that her dyslexia was not her fault and that the bias towards the written word is only prevalent because of the way society is constructed.

Disabled producer Jo Verrent took it a step further and expressed her anger that no one had told her about the Social Model understanding earlier. That caused her to waste so much time trying to fit in and adjust herself, rather than advocate for society to adjust to meet her needs.

Disabled artist Stephen Lee-Hodgkins spoke to Disability Arts Online about how the Social Model understanding had changed his life as a disabled person and helped him to comprehend social injustice. He also spoke about how inclusion can be facilitated if society is determined to make it work.

Disabled writer, poet, and campaigner Kuli Kohli told Disability Arts Online that the Social Model understanding has given her the courage as a disabled person to live life as she wants. It has also opened up many new possibilities for her and encouraged her to raise more awareness of disability within the UK’s Asian community.

Finding Practical Solutions to Disabling Barriers

Introducing the Social Model understanding of disability means focusing on accessible solutions. This is important to see more disabled people engaged in our communities and organizations.

Arts venues are thinking about how to address access barriers in more and more ways. For decades there have been moves in the US and in Europe to address physical and sensorial barriers. Accessible features are common within city environments and public buildings. Ramps, level access, edging and tactile paving are routine within architectural plans. Visual Stories, Audio Guides, Audio Description and Sign Language enhance accessibility for audiences in artistic spaces and venues.

Arts centers, galleries, and theatres have introduced Quiet Spaces where visitors can relax. Conversations about Resting Spaces have also started to take place. These spaces provide an accessible facility for people who need to lie down because of pain, mobility, or other impairment issues.

Beyond Physical Barriers

It isn’t just physical barriers that the Social Model understanding of disability addresses. It also influences the use of language and the role it can play in disabling a person. In adopting the Social Model understanding, the term “disabled people” is used in place of “people with disabilities.” The latter reinforces the belief that the person’s impairment is the problem.

COLIN CAMERON, “WHY WE ARE DISABLED PEOPLE, NOT PEOPLE WITH DISABILITES,” UNION OF THE PHYSICALLY IMPAIRED AGAINST SEGREGATION, 1976:14From a social model viewpoint, disability is not something people have (we are not people with disabilities) but is something done to people with impairments. People with impairments are disabled by poor or non-existent access to the public places where ordinary life happens and by the condescending or unwelcoming responses of those who occupy these places. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society.

For example, instead of asking, “Do you have a disability?” the question that should be asked is “What are your access needs?” This takes away a sense of alienation or lack of recognition and puts us on a more equal footing with a prospective trustee, employee, volunteer, or audience member. It can open discussion about what kinds of support are possible. It also reassures people who may not want to go into detail about their disability, neurodivergence, or long-term health condition.

Pro Tip

Consider having an access rider on hand. An ‘access rider’ is a document that outlines an individual’s access needs. It can help disabled people explain what access means for them. It can support prospective employers, mentors, or whoever else to realize what they can do. The key message is to ask disabled people what barriers they face. It’s about turning your approach on its head. While the Medical Model approach asks, “what’s wrong with you?” the Social Model asks, “what challenges are in your way that make your experience difficult or impossible?”

See it in Action

There are many ways in which organizations have thought about how the social model understanding can be applied to addressing disabling barriers. Here are a few practical examples shared by disabled artists with Disability Arts Online (DAO):

-

Written Word

Live performance artist Pierce Starre talks about how difficult it is for them to ask to apply for opportunities in writing. They ask organizations to think about accepting telephone, audio, or video applications. They also ask if this information can be available in these formats on websites.

-

Online Application Forms

Nicola Smith is a performance artist who has also experienced difficulties in accessing application forms. She uses smartphone videos, sensory materials, Makaton gestures and pictograms, movement and speech, participatory performance, and creative interpretation to communicate with others. She describes herself as being neurodiverse with dyslexia and ADHD, a condition she shares with her son. They communicate with each other through performance play with lots of sensory experiences, words, and images, interpreting the outside world in simple ways.

Nicola describes her do’s and don’ts for online application forms, her primary bugbear. She asks for the organization’s main telephone number or access support details to be put in an obvious place in the main navigation.

-

Integrated Audio Description

Theatre practitioner and access consultant Amelia Cavallo is an advocate for Integrated Audio Description in digital work. She talks about the many barriers that exist for blind and visually impaired people when it comes to taking part in performance, film, television, and art events. IAD can provide the solution to overcoming many of these barriers. It can help blind people get around a space. Describing a space, especially where a blind or visually impaired person has never been before, will help them create a mental image of the performance or exhibition area. Key descriptions of things in the film or theatre space can be included within the narrative during a performance. Another important access tool is the use of certain sounds to indicate what is happening at key moments.