Just over the Minnesota border lies Sisseton, a rural South Dakota town in the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation, home of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate. Half of the town’s population of 2,500 people are Dakota, Lakota and other Indigenous peoples of North America. Like many small towns, Sisseton’s opportunities for youth lie predominantly in sports, which can leave the artsy kids feeling left out. That’s where Nis’to Incorporated comes in.

Nis’to is a nonprofit serving Sisseton’s Indigenous youth. Though the nonprofit was officially established in 2016, the founder, Dustina Gill, has been a lifelong youth advocate. “After working for 8 administrations in the tribal chairman’s office I realized that a non-profit was the best way to go to make change because time is of the essence when working with youth,” says Gill. “This motivated me to start Nis’to. After seeing the limitations of being within the city limits we knew having our own space in the country was the best solution for us. Since starting Nis’to, we have been able to purchase 30 acres of land, build an earth lodge, as well as invest in other projects that prioritize our youth and mission.”

Pronounced “neesh-toe,” Nis’to is the Dakota word for “concern for others outside of oneself.” Gill stays true to the organization’s name by helping kids express themselves through art, build skills important to their culture, and have a safe outlet to attend to their mental health.

DUSTINA GILL, NIS’TO“I realized that instead of waiting for a seat at someone else’s table that wasn’t built for us as Dakota people, we had to build our own table—and we did that.”

At the monthly art club gatherings, kids learn a new skill—everything from beading and sewing ribbon skirts to sap tapping through Nis’to’s food sovereignty initiative—that allows elders to pass down their traditional knowledge. One of the most popular workshops is making moccasins.

“When we do the moccasin workshop, we talk about the importance of burial moccasins and how we need to be prepared when we die. ” Gill says. “We have a handful of moccasin makers here, but it’s hard because when someone passes away, you have four days to do the set, including the bottoms… So having that conversation with those who come to the workshop, all those people are now busy working on their moccasins at home.”

Workshops like these give Gill and the workshop attendees a natural path to discussing grief and mental health.

“Nis’to started out as suicide prevention. We’re a very stacked trauma community, and we have to figure out how to keep things consistent when trauma happens,” Gill says. “We’re trauma-informed, and we talk a lot about healthy grieving, even if we don’t call it that.”

It’s in the framing around the workshops that Gill’s knowledge of those she serves really shines. She draws the kids in with what they want and gives them what they need.

“No one’s going to come to something that says mental health social circle building,” Gill chuckles. “But that’s what it is. There’s all these friendship circles that are either forming or getting stronger.”

Fostering these strong community bonds is a way of addressing generational trauma. Like so many Indigenous communities in North America, the Lake Traverse Reservation had a Catholic orphanage where Native Americans were beaten for speaking their tribal language and abused for practicing their cultural ways.

“You still see the historical trauma and effects of that today. Understanding what that did and how it’s still here is why we do what we do,” says Gill. “The children we work with are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of a lot of the survivors, and some were raised very Christian because of the punishments they received… I saw kids getting beat up for being ‘too Indian.’ So we try to help without cultural shaming.”

Nis’to is also making strides in helping the community repair that language wound by incorporating the Dakota language into their workshops.

“I write curriculum at the tribal college here for the Dakota language, and all the curriculum I write is task-based learning,” says Raine Cloud, a Dakota speaker and translator and mom of a daughter who attends Nis’to’s events. “It’s a curriculum around making things or hunting, fishing, gathering, or gardening, so you’re learning both specialized language and the everyday language we use. Like, how do you say ‘needle’? How do you say ‘thread’? That’s how we learn the language in a way that doesn’t feel like a class.”

While the monthly art club also does non-culture-specific forms of art, like still life drawing, Gill and the kids sometimes chafe at having their ancestral folkways called art.

“When [non-Indigenous people] call moccasins art, it’s like, what? We use these,” Gill says. “We ask ourselves how do we translate it better, so it’s not a pony show.”

This is something Gill and Cloud are constantly fighting: non-Indigenous people wanting access to Dakota culture without addressing the holistic needs of the community. Or there being barriers to entry, such as those who own community spaces allowing Dakota people to use the facility, but only if they don’t smudge and set off the fire alarm, for example.

“They only want us when it looks good and when there’s tourism value, but you can’t just have the pretty part. You can’t have our jingles and feathers when it looks good and never anything else when it’s not convenient. We’re not a hobby.” Gill says.

“Sometimes people want the Native American presence so they can say it’s Indigenous, and that’s the only time you get called to the table,” says Gill. “I realized that instead of waiting for a seat at someone else’s table that wasn’t built for us as Dakota people, we had to build our own table—and we did that. We bought 30 acres of land and built an earthlodge. We’re starting our monthly gathering out there in March.”

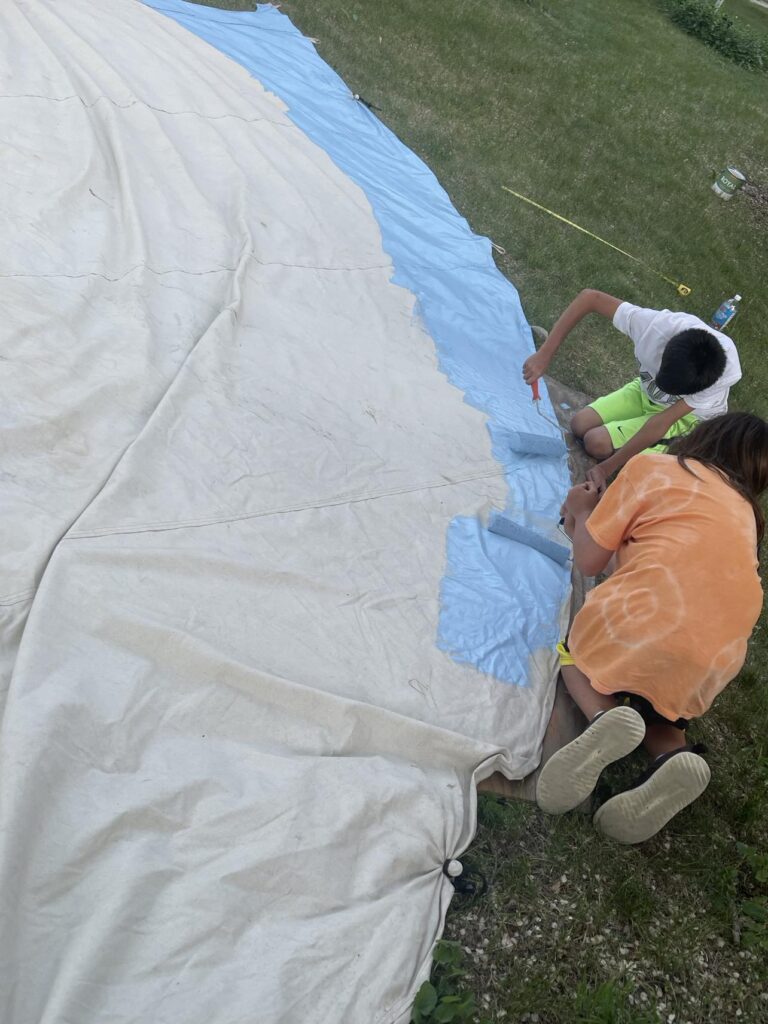

Having the earthlodge will allow Nis’to to expand their mission even more because they’ll finally have a space to make arrows, tan hides, and follow the 13 moons that mark the Dakota annual passage of time. There, they can smudge and burn sage all they want.

For Raine, this mission is personal.

“I have a daughter, and I want things to happen for her and all the kids. … I love teaching because I feel like our elders have taught me things, and it’s not mine to hoard,” Cloud says. “Once, a long time ago, everybody knew this stuff, and we need to get back to that.”

As Nis’to continues to grow, one of their goals is to document their workshops and make how-to videos in Dakota. As the lead translator, Cloud will be helping preserve the community’s ancestral knowledge in the language it was meant to be communicated in to create a digital library for educational institutions and others to continue teaching these important skills.

RAINE CLOUD, NIS’TO“I feel like our elders have taught me things, and it’s not mine to hoard. Once, a long time ago, everybody knew this stuff, and we need to get back to that.”

Nis’to founder, Dustina Gill, was a key community stakeholder with the Sisseton Arts Council in Sisseton, SD as part of the pilot cycle of the We the Many program. We the Many is a program that supports communities in the creation of their own unique artist residency experiences, encouraging the exchange of voices, cultures, and ideas relevant to each community context. We the Many is a project of Arts Midwest with generous support from the Mellon Foundation and in partnership with the South Dakota Arts Council.