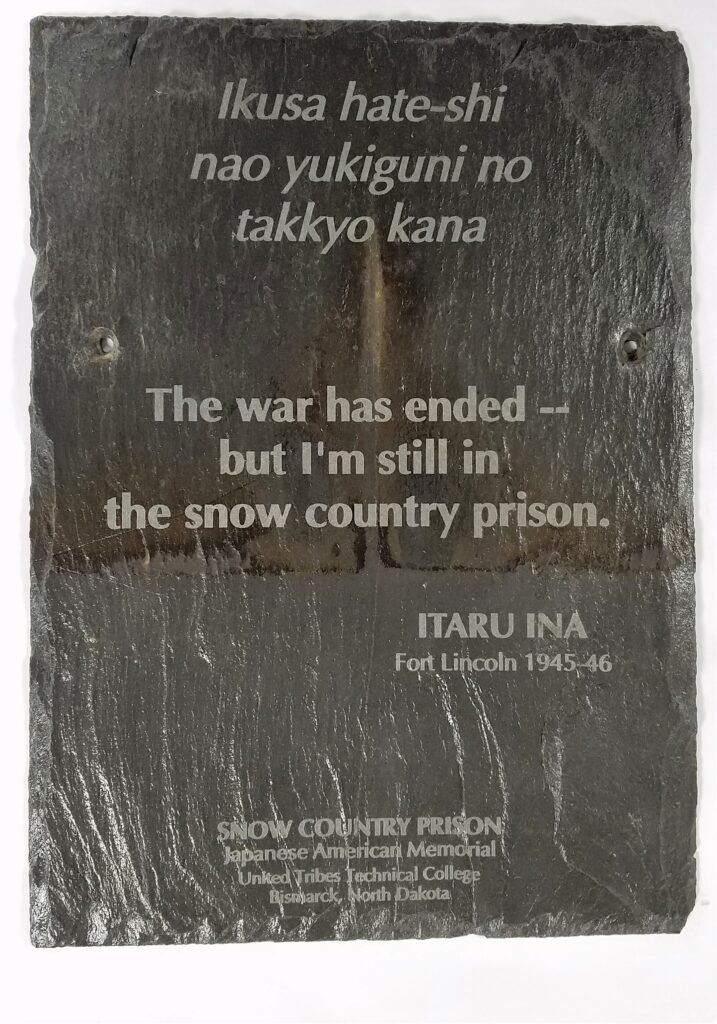

In 1945, Itaru Ina, a Japanese American internee at an prison camp in North Dakota, wrote this haiku:

The war has ended

but I’m still in the snow

country prison.

Three years before—not long after the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Empire of Japan during World War II—over 120,000 Japanese Americans, mostly U.S.-born citizens, were forcibly removed from the West Coast by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. This order stripped those of Japanese ancestry of their civil rights. They were moved through 15 assembly centers and into 10 confinement sites, also known as concentration, or imprisonment camps. While the United States said that it was done for national security reasons, many will argue that it was also a manifestation of racism. One of those prison camps was at a military post in Bismarck called Fort Lincoln.

Ina’s experience—as well as his reference of Fort Lincoln as “snow country prison”—and the tragic history of internment are now being honored with the building of The Snow Country Prison Japanese American Internment Memorial. The goal is to bring healing to the troubling wartime treatment of Japanese and Japanese American civilians. It’s being built in a familiar place in South Bismarck.

Highlighting Resistance

The site of the former Fort Lincoln Internment Camp is now the campus of United Tribes Technical College (UTTC). College administrators, staff and several descendants of Japanese American internees have come together to create a memorial on campus to recognize and honor more than 1,600 first and second generation Japanese American citizens, who were incarcerated at this camp. Former internees and their relatives have visited the site for the last 40 years to reflect on the history of what happened. With the college’s support, Japanese and Japanese American visitors have been welcomed to tour the site, share their stories, and participate in ceremonies.

DR. LEANDER McDONALD, PRESIDENT OF UNITED TRIBES TECHNICAL COLLEGE“This is important work, to not only recognize what happened to our Japanese American relatives but also to ourselves. This memorial will show that we’re still here, that we’ve survived and that now we need to move ahead.”

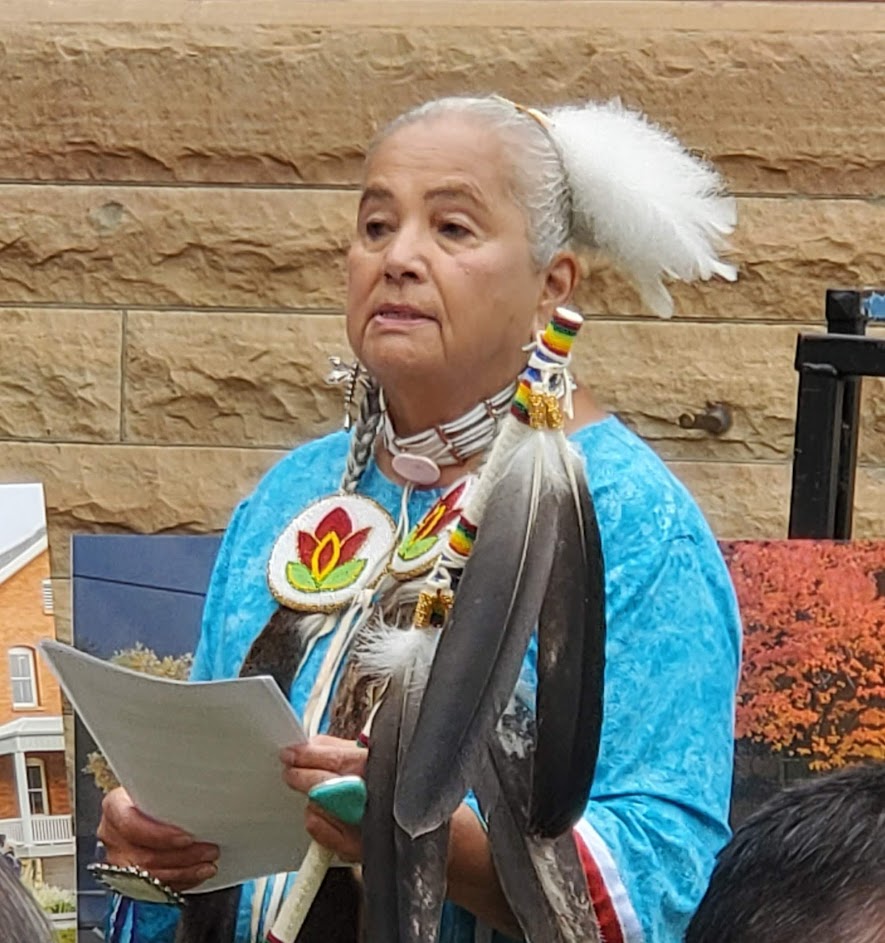

There is very little awareness about this chapter of American history and the role played by the Fort Lincoln Internment Camp. The Snow Country Prison Japanese American Internment Memorial at United Tribes Technical College is an opportunity to highlight a story about resistance to oppression and raise up the memory of those who suffered incarceration just for standing up as citizens. This is very similar to the persistence of tribal people in sovereign nations, within United States borders, who have also been challenged throughout history. Dr. Denise Lajimodiere, North Dakota Poet Laureate and citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa who spoke at the memorial ground blessing event says, “Reservations are just similar to internment camps. We’ve called them internment camps, concentration camps before we were put there. The Japanese also were rounded up and put in internment camps. There’s a commonality there.”

Bonding of Cultures

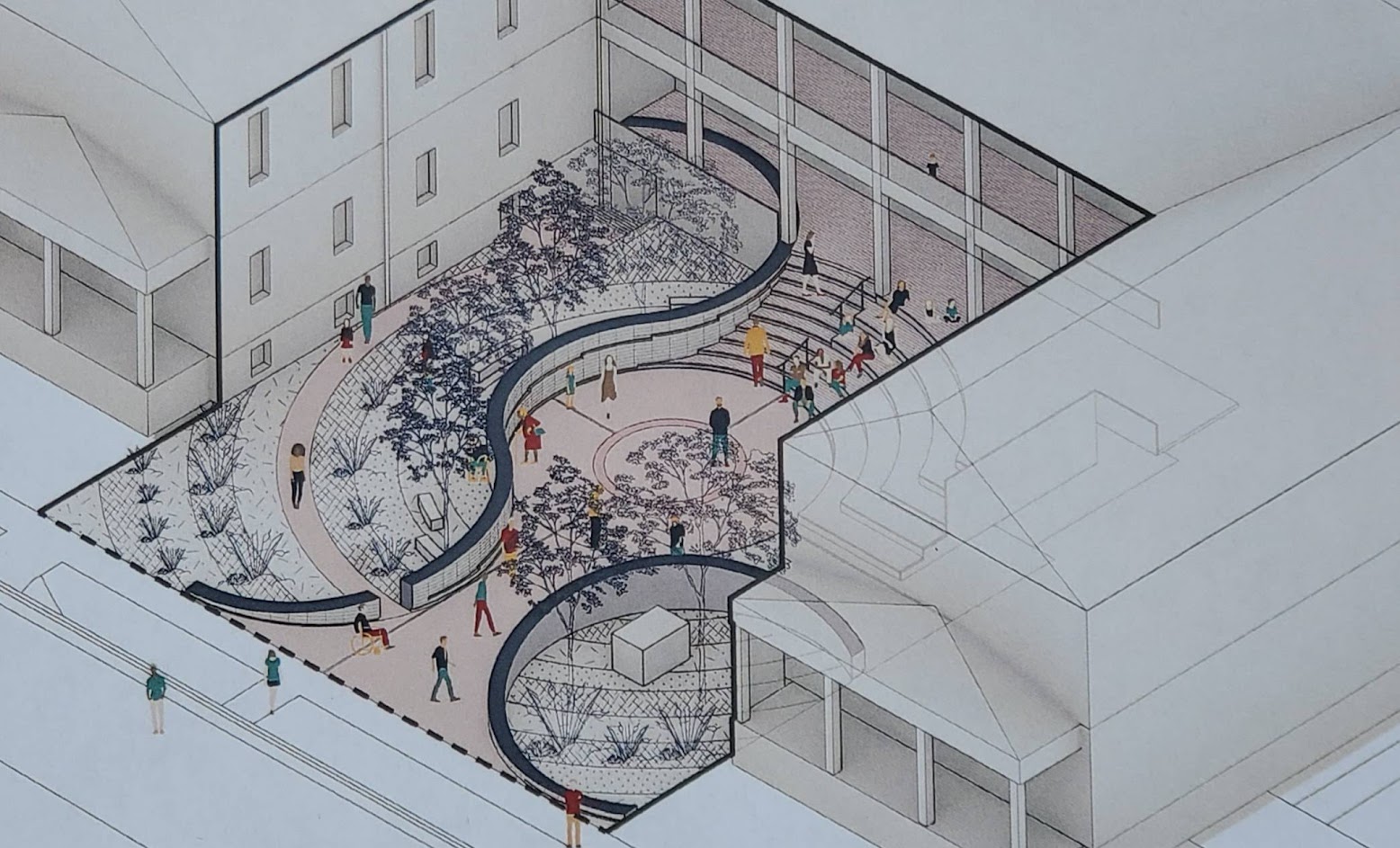

This memorial is the first of its kind to acknowledge solidarity between Indigenous and Japanese American communities. The design of this memorial is based on a process in Japanese ceramics that uses a lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum to mend broken pottery, called kintsugi. It highlights the cracks and turns them into a part of the object’s history and story. In this case kintsugi represents the bonding of cultures and communities.

Kintsugi will appear through the memorial’s wall, as a visible stitch across the site. This will also serve as a receptacle for the tsuru or paper crane offerings that bring healing and wholeness to this space over time. The walls are made of slate roofing tiles, reclaimed from the former prison’s roof. It will also have amphitheater seating in the courtyard to provide gathering space and opportunities to connect to exhibitions inside and to the campus cultural trail. The 4- Directions Drum Circle will serve as the ceremonial center and offer solitary reflection while visitors take in unique landscaping and native plants. This serves as a shared ceremonial space that honors the spirit of endurance and solidarity that has been exemplified by Japanese American and Indigenous resilience.

UTTC President Dr. Leander McDonald explains how this memorial is a healing wall. “This is important work, to not only recognize what happened to our Japanese American relatives but also to ourselves. This memorial will show that we’re still here, that we’ve survived and that now we need to move ahead.”

An architectural group called MASS (Model of Architecture Serving Society) Design Group has partnered with the tribal college and members of the Japanese American community to create this unique monument representing intersectional social justice. The internationally renowned design firm’s mission is to build and advocate for architecture that promotes justice and human dignity.

The purpose of the memorial is twofold: the first is to honor the legacy of Japanese Americans who were interned at Fort Lincoln and the other, to help educate future generations. Through education, empathy building, and gathering together, the memorial promises to catalyze a broader reconciliation process around intersectional patterns of racial oppression and violence. It can serve as a model for other former camps around the country as planners search for healing through the use of acknowledgment and memorialization.

President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Rights Act of 1988 which apologized to Japanese Americans for the unjust removal and incarceration, and provided $20,000 to each living survivor. More information on the internment of Japanese Americans can be read in the United States Government National Archives.

Itaru Ina’s daughter Satsuki Ina also wrote about her experience as a survivor and descendant of the Fort Lincoln Internment Camp. She’s a doctor of Psychology specializing in intergenerational trauma. She was born at the Tule Lake Segregation Camp in California. She directed the 1999 documentary, Children of the Camps, about her lived experience. Her father was sent to North Dakota while the rest of her family stayed in Tule Lake Segregation Camp.