In The Round House, Geraldine Coutts, a Chippewa woman, is sexually assaulted in the vicinity of a sacred roundhouse. The roundhouse is on reservation land, where tribal courts are in charge, but the suspect is white, and tribal courts in the summer of 1988 can’t prosecute non-Native people. Federal law would also seem to apply, but the assault may have taken place on a strip of land that is part of a state park, where North Dakota’s authority is in force, or on another that was sold by the tribe and is considered “free land,” administered under a separate set of statutes.

Traumatized by the assault and reluctant to reveal what happened to the police, her husband, or her son, Geraldine finds refuge in solitude. Her then 13-year-old son, Joe, pursues his own quest for justice after deciding to become a public prosecutor himself. In tracking down his mother’s attacker, Joe searches for the answer to the question of what makes a person turn violent — and what society should do with violent people.

Director of Library and Academic Services Marc Boucher said that bringing the NEA Big Read to LSSU allowed them to discuss issues like violence against women, Native land jurisdiction, prejudice, cultural heritage, trauma, and coming of age through multiple lenses. “Having different communities come together and learn from each other was enriching and very educational,” he said. “We are dealing with these issues in our own backyards and bringing some of them into the foreground of discussion gives us all the opportunity to be active players in helping move forward rather than being ignorant and sweeping such issues under the rug.”

LSSU’s Arts Center Director and Assistant Professor of Theatre Thomas Meacham, Ph.D. chose this year’s novel with Boucher. Although it is set in 1988 on a reservation in North Dakota, they say it is still relevant and reflects the struggles that Native American victims of violence face when trying to find justice. There are Native American families in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., that have experienced the murder of their daughter/sister/mother/friend due to domestic violence and human trafficking. Those families are still waiting for justice for their loved ones.

Connecting with Community

Students attending LSSU are living and learning within a unique community. The 115-acre campus sits on the site of the former U.S. Army’s Fort Brady, with fourteen of LSSU’s buildings being listed on various historic registers. The campus overlooks both Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, the St. Mary’s River, and the Soo Locks.

Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan shares the international border with Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. Between both cities, the population is about 100,000. Members of Native American tribes and Canadian Aboriginal communities call the area home. Located in the Upper Peninsula are five tribes: Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians; Keweenaw Bay Indian Community; Hannahville Indian Community; Bay Mills Indian Community; and the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

Mark BoucherThe power of hearing about others’ experiences…

can help build bridges with people you might not have ever thought you might engage with.

As part of the Big Read Kick-Off event, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, Bryan Newland, who at the time was the president of the Bay Mills Indian Community, was the keynote speaker. He is a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community (Ojibwe), and before being elected president he served as Chief Judge of the Bay Mills Tribal Court. From 2009 to 2012, he served as a Counselor and Policy Advisor to the Assistant Secretary of the Interior – Indian Affairs.

After Newland’s address, a panel discussion was held featuring Newland, Chief Judge of the Sault Tribe Jocelyn Fabry, and Executive Director of the Diane Peppler Resource Center, Betsy Huggett.

Boucher said the discussion held at the Bayliss Public Library was powerful because of the participation of community members who brought their real-life experiences to the table. The panel focused on tribal law enforcement divisions, who they can prosecute, and barriers to enforcement. At the panel, a woman in the audience spoke about recently discovering her Native heritage.

“This woman was told, or felt, that she should be embarrassed about her own cultural heritage,” said Boucher. “But the discussions that were happening and her own self-discovery and hearing about the pride, connection, and community, and helping others around her in that discussion learn about it from her own personal experience was very powerful.”

Dancing into Understanding

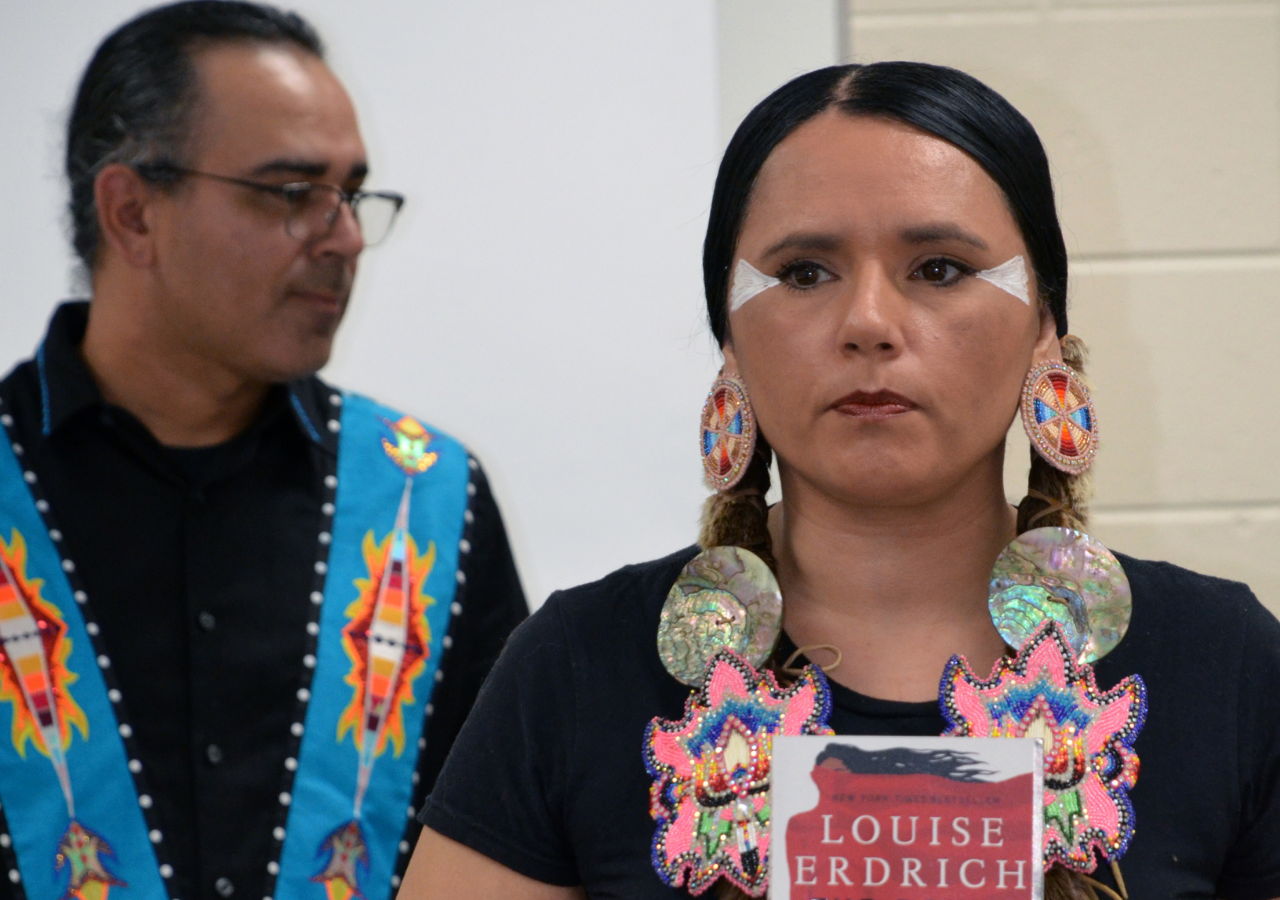

After a semester of film screenings and panel discussions in 2020, programming was suspended because of the COVID-19 pandemic. In October 2021, programming resumed when Woodland Sky Native American Dance Company began its week-long residency at LSSU. Students, faculty, and members of the community engaged in lectures about regalia and the celebration of traditional ceremonial practices; participated in craft-making workshops and dance classes; and were exposed to Indigenous art and jingle dresses on display in LSSU’s Art Gallery.

Meacham says that the workshops allowed students to learn the cultural background and meaning behind the crafts they made.

As a closing activity, Woodland Sky performed dance and spoken word about the necessity for the preservation and celebration of Indigenous identities. “It was a wonderful way to see so much of what was discussed prior to the pandemic realized through the arts and artistic expression,” Meacham said.

Meacham and his team worked to incorporate the Big Read’s themes of land sovereignty and jurisdictional issues with Woodland Sky Dance Company’s residency and final performance. Translating issues through the medium of dance creates “a very visceral emotive sense that you might not get [by] reading the book,” Meacham said. “The arts are well-positioned to bring us into these themes in a whole new way. Even though it has been some time since students read the book, those same themes can come alive again through dance.”

“The main reason myself and Shane Mitchell co-founded the dance company was to continue sharing stories and teaching, and really show the beauty of our culture,” Woodland Sky co-founder Michelle Reed added. “We try to bring it to the next level where people in the mainstream would want to see and watch it and learn about who we are, instead of just sticking with preconceived ideas that they grew up with about Native people.”

During the residency, several students who are part of the Native American Center on campus told Meacham that they had not felt visible on campus. “These residencies and [the] artists on campus provided students an extended experience that would not have been possible without this grant,” said Meacham.

Boucher said that LSSU’s strategic plan identified strengthening connections with Native American people, land, customs, and history. Through the Big Read, he says the visibility of Native American culture on campus has increased. Reading The Round House encouraged students, faculty, staff, and the community to engage in a common set of ideas and see them from multiple perspectives.

“The power of hearing about others’ experiences and seeing how they are either similar or very different from your own can help build bridges with people you might not have ever thought you might engage with,” said Boucher. “Joe’s life [as] a 13-year-old boy growing up in the Midwest allowed me to see how my own (non-Native) culture is in some ways so much like his.”

The National Endowment for the Arts Big Read is a national program administered by Arts Midwest that helps communities realize the benefits of reading together. Each year, grants are given to about 75 community reading programs around the country who set up creative events and opportunities for their community to read and discuss one book together. Since 2006, more than 1,600 NEA Big Read programs have taken place in every U.S. state.