When Columbus, Indiana, was founded in 1820, no one could have predicted the city would become a must-see destination for art and architecture lovers. Just 40 miles south of Indianapolis, along the White River, the mid-sized city is known for its modernist buildings and plethora of public art, all crafted by some of the greatest design-minded thinkers of their time. Most buildings were built between 1942 and 1965, and seven have National Historic Landmark designations, as named by the National Park Service.

Modernist style and architecture came about around the same time as the midcentury modern aesthetic, growing in appreciation after Art Deco’s popularity declined. The hallmarks of modernist architecture are what, at the time, were new and innovative building materials, including steel beams, large plate glass windows with no leading, concrete, and drywall.

Philosophically, the movement was known for its practicality: minimalist design in which every aspect of the build had a clear purpose and function, with no unnecessary adornment. Furniture, such as sunken couches and window seats, was often built into the building, and large, open spaces were common. The belief was that these Modernist buildings would feel more welcoming and less intimidating to visitors than architectural movements of the past known for lavish ornamentation, such as Gothic, Baroque, and Beaux-Arts.

What makes the presence of so many Modernist buildings and public artworks so special is their sheer volume for a city of Columbus’ size and that the city hired architects from all over the world for the task. This decades-long undertaking was made possible by the Cummins Foundation.

Cummins, the engine and industrial materials design and manufacturing company, was founded in Columbus over a century ago and is still in business today. J. Irwin Miller, who held multiple positions at Cummins, including CEO, established the Cummins Foundation in 1954 and informed city leaders that the foundation would pay for the architect’s fees as long as it was for public buildings, and they commissioned up-and-coming engineers and architects.

Those commissioned include the Finnish-American architect Eliel Saarinen; his more famous son, Eero Saarinen, perhaps best known for designing the Gateway Arch in St. Louis; Chinese-American architect I. M. Pei; Robert Venturi; Argentinian-American architect César Pelli; Richard Meier; Latvian-American architect Gunnar Birkerts; and Harry Weese, among others. The diversity of architecture earned Columbus the nickname “Athens on the Prairie.”

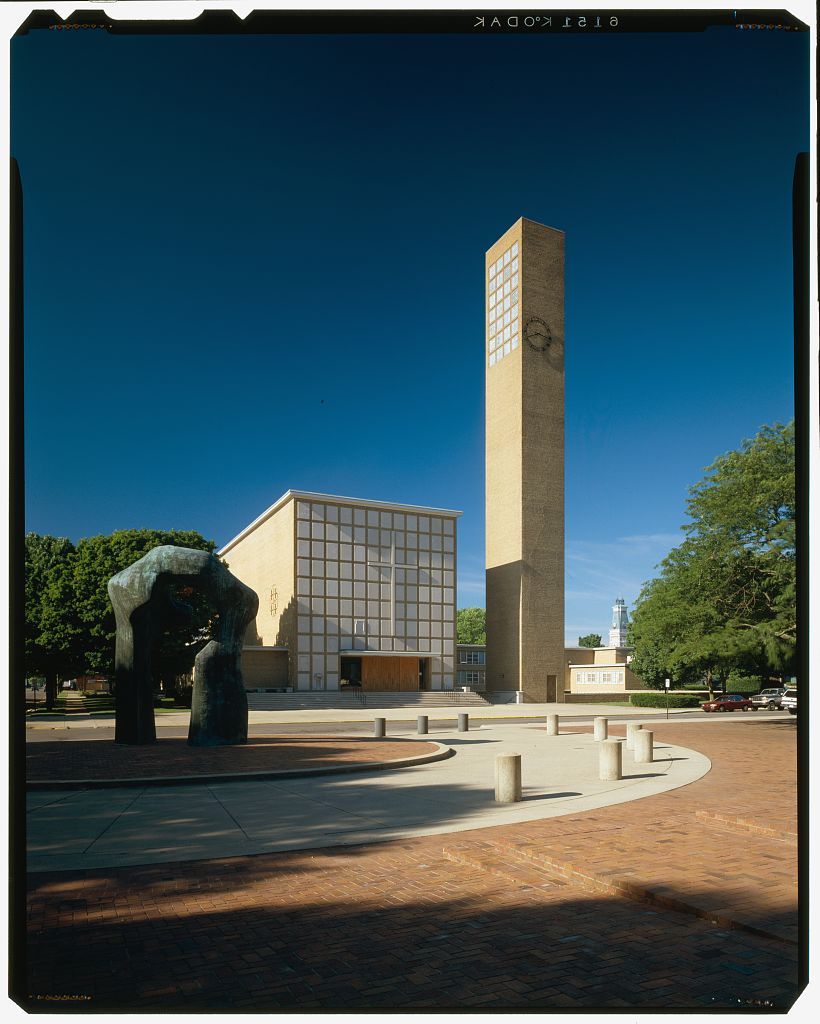

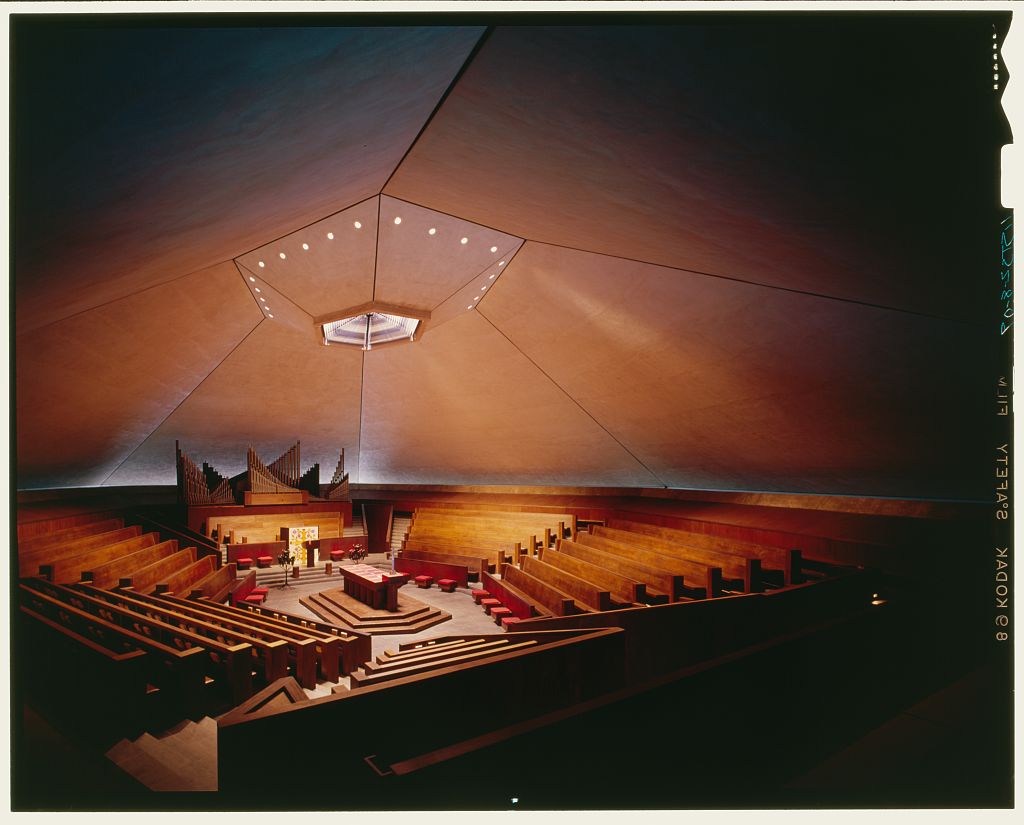

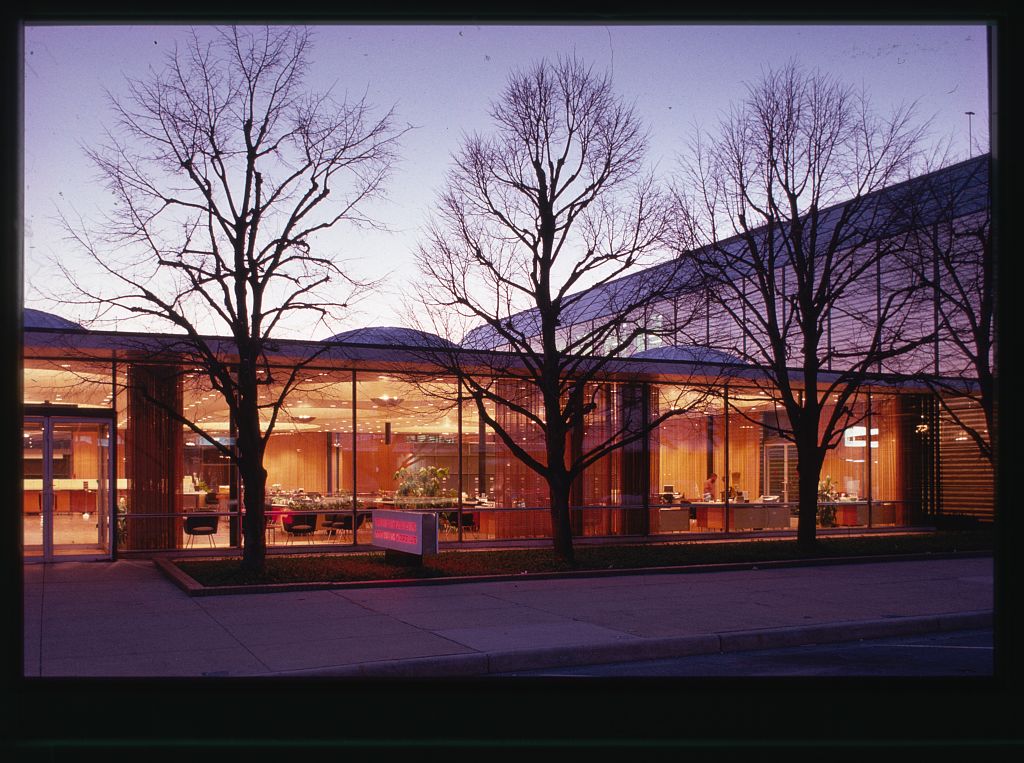

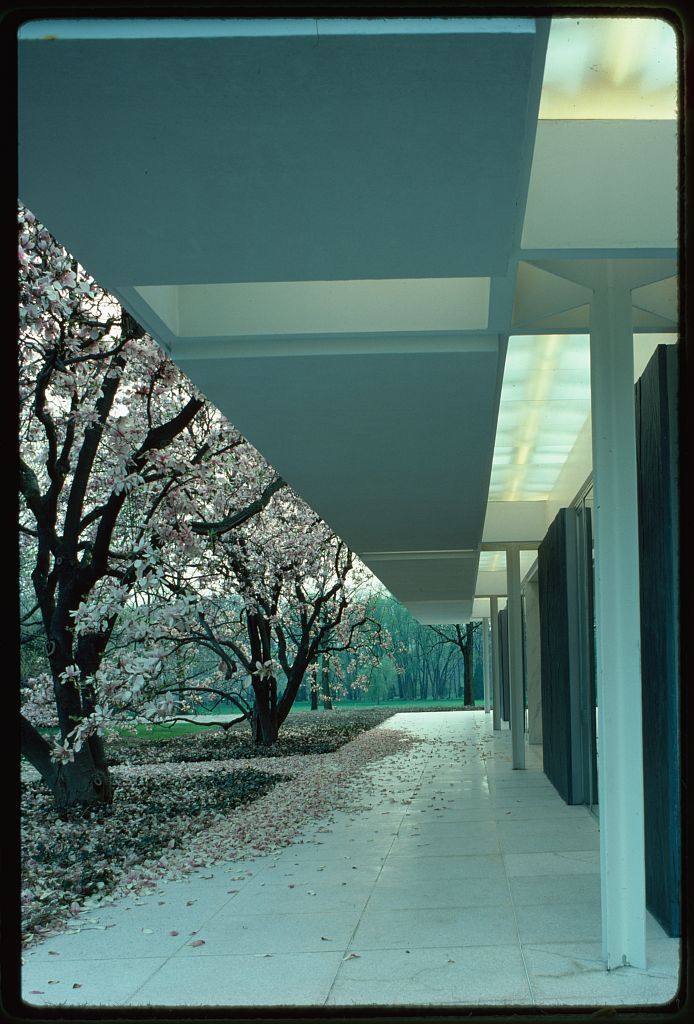

While there are more than 60 Modernist buildings in Columbus, seven of the most popular and well-known are listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Harry Weese’s First Baptist Church, Eliel Saarinen’s First Christian Church, John Carl Warnecke’s Mabel McDowell Elementary School (now an adult education center), the firm Myron Goldsmith of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s The Republic Newspaper Office, and three buildings by Eero Saarinen. The younger Saarinen’s contributions include the Irwin Union Bank, now the Irwin Conference Center; the hexagonal North Christian Church known for its towering spire; and the Miller House, one of the few private residences Saarinen designed and owned by J. Irwin Miller and his wife Xenia Simons Miller while they were alive, the house was donated to the Indianapolis Museum of Art upon Xenia’s passing since J. Irwin preceded her in death.

Captured in Film

To get a taste of what Columbus offers, check out the film Columbus. Starring John Cho and Haley Lu Richardson in the protagonist roles, the film follows Jin, a Korean man who travels to Columbus after his architect father arrives in the city to give a talk and has a health episode that leaves him in a coma. There, he meets local library worker and architecture enthusiast Casey, who has chosen to put her own architecture dreams on hold to care for her mother, who is in recovery from addiction to meth. Many of the buildings mentioned above are featured in the film.

Columbus was created by filmmaker Kogonada, who was born in South Korea and raised in Indiana. He visited the city on a holiday break and was so moved by the architecture that he decided it had to be part of the first feature-length film he made. The film debuted at Sundance in 2017 and garnered a whopping 32 award nominations and 12 wins throughout its run on the film festival circuit.

The setting of Columbus and its many architectural wonders was in no small part a factor in the film’s success. As film critic Richard Brody wrote in his article in The New Yorker, “Those buildings provide an extraordinary premise for the drama, which is a visionary transformation of a familiar genre: a young adult’s coming-of-age story. For once, that trope doesn’t involve a sexual awakening or a family revelation; it’s the tale of an intellectual blossoming, thanks to a new friendship that arises amid troubled circumstances.”

While Columbus may be known for its Modernist buildings, the city continues to prioritize architecture and innovative design by commissioning more and more public art. In odd-numbered years, the city hosts Exhibit Columbus, a weekend exhibition of the latest artworks that includes many free events for the public. Experts and enthusiastic laypeople alike can attend talks with designers and architects, go on guided tours, and bask in all the inspiration Columbus has to offer.

All photos in this story courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Balthazar Korab Collection.