One piece of paper may be all that’s standing between you and having your art seen. No editor, no publisher, no product number needed.

This independence is a pillar of the world of zines—small scale stories, observations, or images often printed on plain copy paper. Any genre goes.

“If you make your own work and you’re putting it out yourself, you’re just eliminating that gatekeeping. You’re getting it out,” says Liz Mason, owner of Quimby’s Bookstore in Chicago, the birthplace city of zines.

The store sees non-Midwest waves of customers exclusively for its consigned zine collection.

The zine timeline likely started with science fiction fan writings, authored mostly by women, in the 1950s, Mason says.

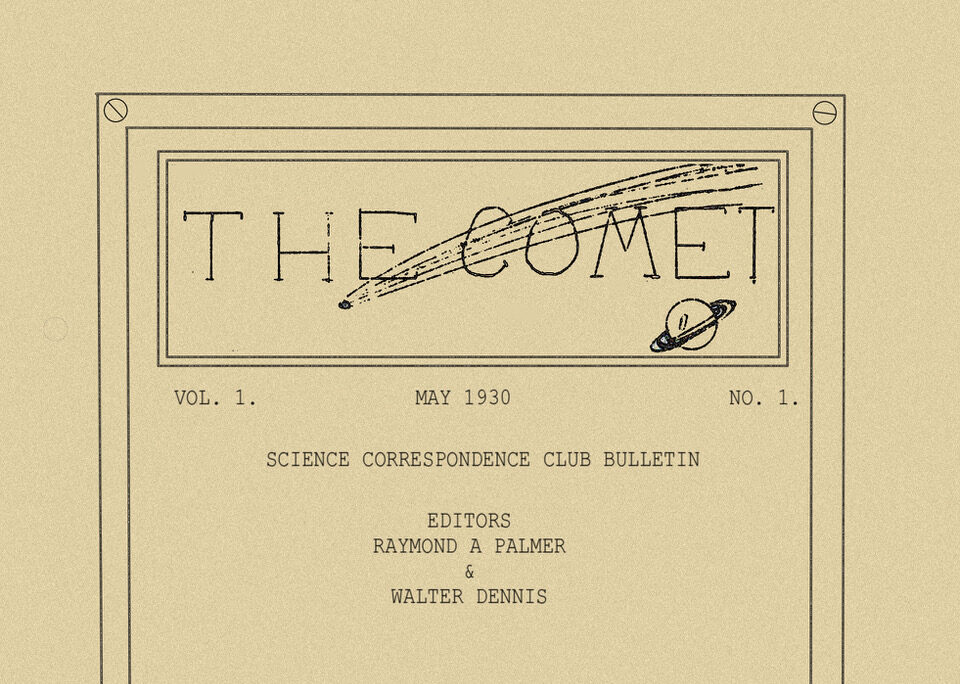

The first recorded was Chicago’s sci-fi fanzine Comet, published by the Science Correspondence Club in 1930. Following that, artistic movements held zines up, namely punk and riot grrrl waves.

Mini zines and comics made (and still make) their appearances: The art form isn’t “back”—it never left.

Just Ink and Paper

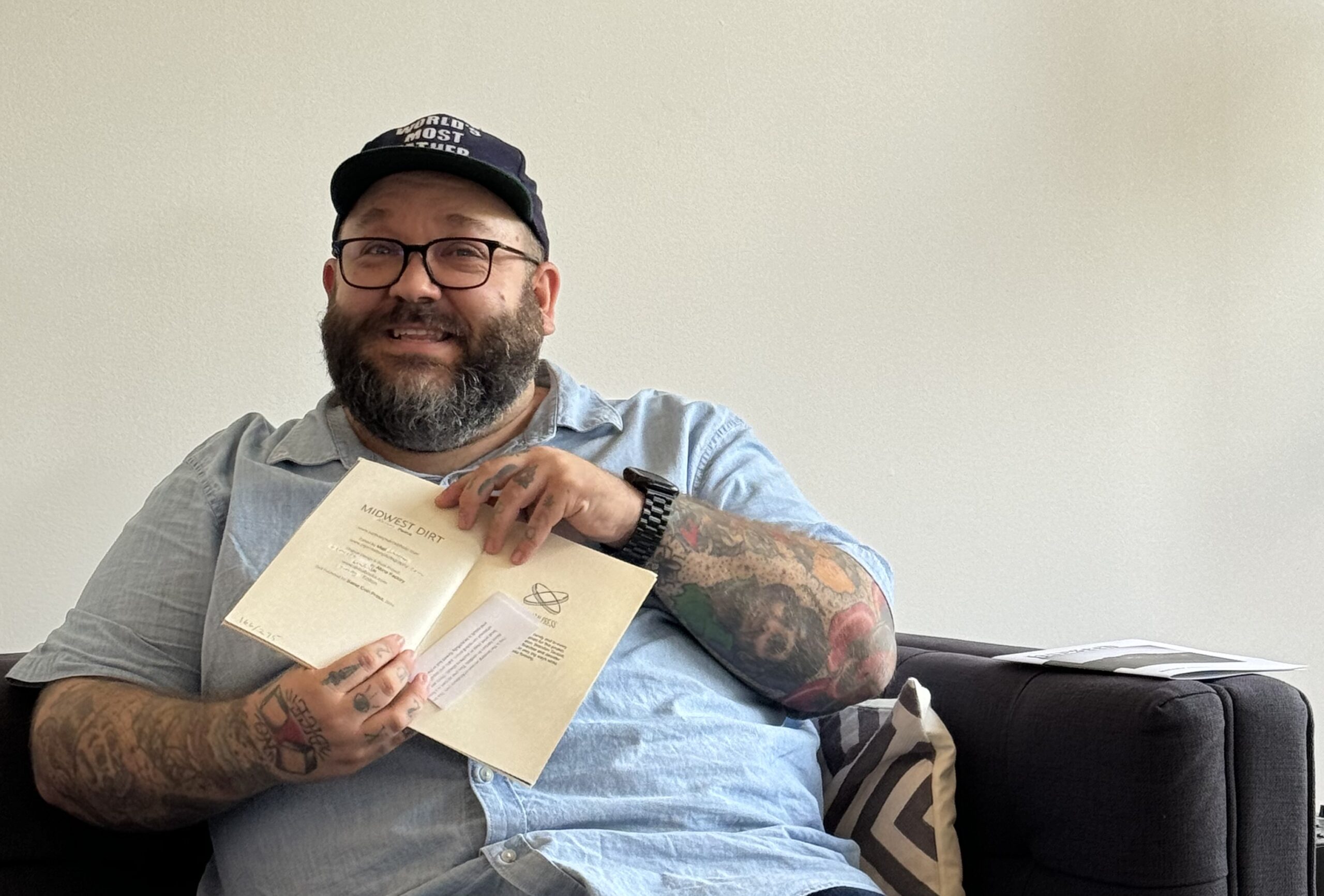

Rural southern Illinois zinester Nathan Pearce has been making zines for the last 15 years.

He defines them as “any sort of self-published or DIY publication that can take a lot of forms,” including stapling pages together, self distributing, or photocopying.

The photographer uses zines to distribute his art.

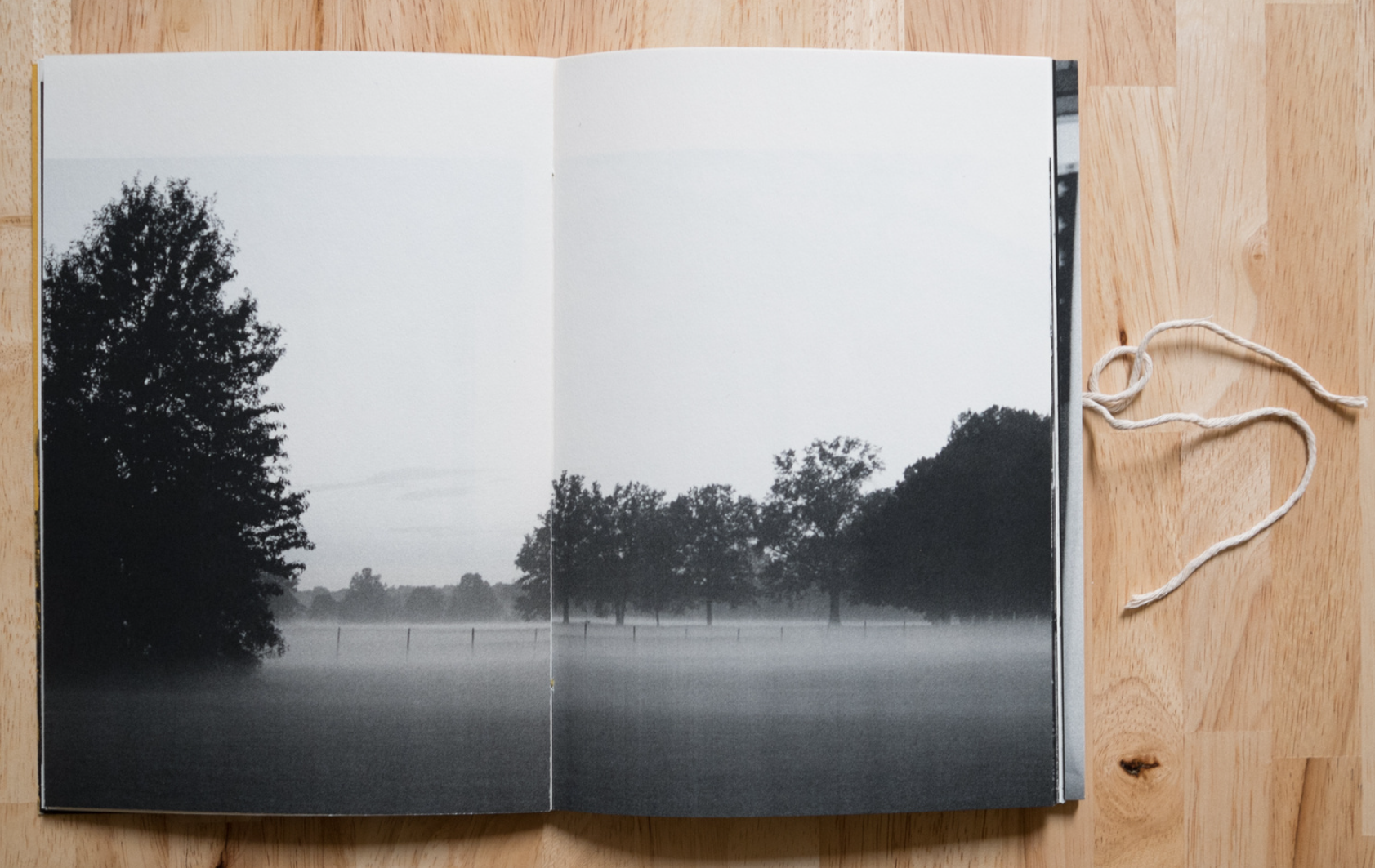

Pearce’s black-and-white works draw you into Midwest detail. Steady horizons hold you; everyday scenes soothe. And these images wouldn’t have the prevalence they have today if not for zines.

“That made a big difference in my career,” Pearce says about self publishing.

“People started to pay attention more because I was able to distribute more printed things. Just waiting for someone to give me a show, give me an exhibition of my own didn’t necessarily make sense for me.”

He could come up with a project or book, then do a small print run (5-10, sometimes 20). People would buy them. And all it cost Pearce was ink and paper.

Midwest Prominence

“The Midwest is that kind of scrappy DIY can-do,” says Mason, who has been making zines for over two decades. The region holds a prominent spot in zine culture, with active communities even in smaller cities and towns.

Pearce’s work wouldn’t exist without rural Illinois.

“It’s sort of hard to put into words … the quiet landscape … there’s something both beautiful and maybe sometimes a little ominous,” Pearce says of the photos he takes.

Mason says there are all the reasons in the world to venture into this folk art world—either making or buying.

They’re less expensive than books, too. And zines = unparalleled community.

“If you are a fan of a zine or a comic that you’ve bought, usually those people are very easy to contact, and you might end up developing a relationship with them,” Mason says.

Enter this niche, and you’re likely to come out of it with a bestie—and an eight-page manifesto.