There’s a low chanting of a haka on a nearly 100-degree day on the campus of the United Tribes Technical College in Bismarck, North Dakota. The sound grows louder as you approach the Lone Star Veterans’ Powwow Arena where about 20 Māori citizens perform their ceremonial dance as gratitude, making their way to the center of the powwow circle. The haka reverberates as the delegation is greeted by several citizens and elders of the Oceti Sakowin, the MHA Nation, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, and the Sioux Valley Dakota (Manitoba).

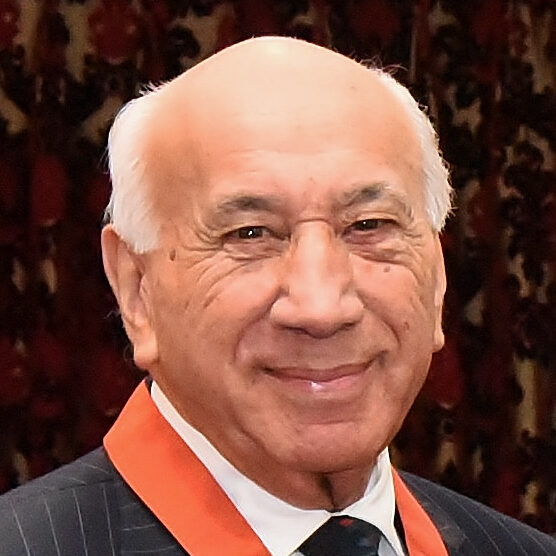

The Māori group were special guests of the Standing Rock Nation. The delegation accompanied the guest of honor, Sir Timoti Kāretu, a Māori language warrior from Aotearoa (New Zealand), who is highly regarded in Indian Country. This is the 86-year-old’s last visit to the United States.

Kāretu is considered a master of te reo Māori (the Māori language) and is recognized nationally and internationally for his knowledge and work in the language. In 1972, he helped co-found the first Māori Language Commission in New Zealand and in 1987, Kāretu oversaw the implementation of the Māori Language Act. He is also the inspiration behind the development of many language schools across Indian Country.

DJ DRIVER JR., HIDATSA LANGUAGE TEACHER FROM THE MHA NATION“It was chosen not to teach [the Indigenous language] because of what our speakers faced and the repercussions. But here today we start to have these immersion schools coming up… And I’m blessed and honored to have my children go through an immersion program.”

The Ripples: Learning from the Best

Over a decade ago, Kāretu visited the Standing Rock Reservation to talk about successful Māori language revitalization efforts. Event organizer Tipiziwi (Young) Tolman, a Standing Rock citizen, recalled that during that visit Kāretu’s words were stern, but they came from a place of love and compassion. They resonated with many Indigenous language speakers and inspired them to do the hard work of making language schools a reality in their respective tribal nations.

Tolman is also a master of language revitalization for her people. She has a master’s degree in Indigenous Language Revitalization from the University of Victoria, BC, and is currently on the Teaching & Learning Faculty at Washington State University. While exploring the idea of creating a Lakota language immersion school in Standing Rock in 2009, Tolman had the opportunity to learn directly from Kāretu in his homelands. She brought those teachings back and eventually helped to establish the current Lakota Immersion School in Fort Yates, North Dakota in 2012. She attributes the success of Indigenous language schools across Turtle Island directly to Kāretu’s efforts.

Several elders shared their stories of learning a language they were punished for. DJ Driver Jr., an elder and Hidatsa language teacher from the MHA Nation said, “If we went to a boarding school, we got in trouble. When we got home and tried to speak our language, the moms and dads, grandmas and grandpas said “you know we don’t want you to do that, because we got in trouble for that. They hurt us for speaking our language.” So that is how the divide started between speakers and non-fluent speakers—from the boarding school era.” As he shared stories of what it was like growing up, he said, “It was chosen not to teach [the Indigenous language] because of what our speakers faced and the repercussions. But here today we start to have these immersion schools coming up… And I’m blessed and honored to have my children go through an immersion program.”

Driver spoke of how Kāretu’s work and the Māori language kept coming up in the research and references that went into building the immersion school in their community. “We took the groundwork that was laid out in your homeland… Many said, “you know we could do this, because there’s a tribe over there that has done it already and they have speakers now, so we can move forward too,”’ he said referencing Kāretu’s influence. “You have made your presence known in Indian country, and also throughout the world. So, as far as language revitalization is concerned, the world owes you a thank you.”

There is beauty and serendipity in listening to a young child speak their language, knowing that they won’t go through what their elders experienced. Students from two immersion schools showed their gratitude and introduced themselves to the delegation in Lakota as the crowd cheered them on. Five young students from an immersion school in South Dakota closed the honoring ceremony with a song called ‘Wopila,’ or ‘Thank You’ in Lakota.