With 25 years and nearly 100 classes under his (tool)belt, David Susag is who we’d like to dub an official folk school fanatic.

The Lanesboro, Minnesota, artist started taking traditional courses in 2000, from cooking and rosemaling to knife-carving and skinnfell.

“I haven’t done any weaving there,” Susag says matter-of-factly, with a hint of a laugh. “So that’s about the only thing I haven’t done.”

“There” is Vesterheim Folk Art School (part of the historic Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum) in Decorah, Iowa. Susag, who also teaches, is one of many students learning the art of making new things—but keeping it old-school.

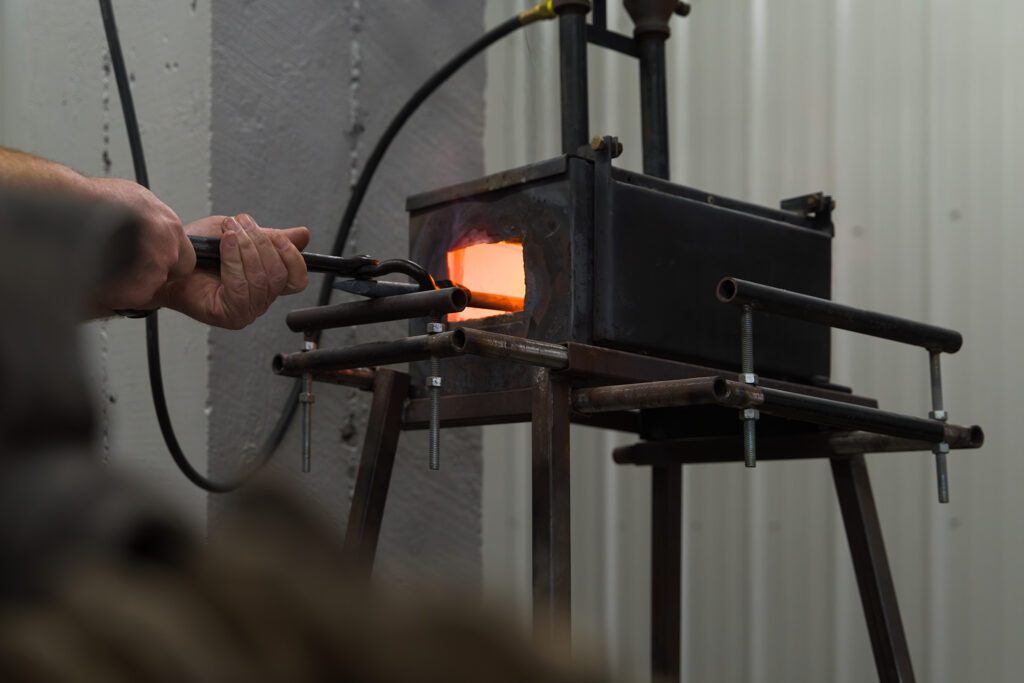

Vesterheim opened a new forging studio this spring where learners can hammer superheated metal into, say, tools or wall hooks. Think: fire, hammers, and lots of clanking.

Susag has forged chisels and scorp tools for his wooden bowl turning practice, which is perhaps his magnum opus. From craft to craft.

“There’s so much of this that’s so interconnected,” he says. And he knows what he wants and needs in a finished product; he’s even bought his own at-home gas forge.

“When I’m making a knife, I can kind of make the shape traditional, but I can also make it to fit my hand.”

Greg Walton, an education program coordinator at Vesterheim, says the DIY nature of folk art has been a pinnacle of Decorah since it was settled by Norwegians in the mid-1800s. The town is full of Scandinavian flair and is often called “Iowa’s Norway” (not to be confused with the actual city of Norway, Iowa.)

“It’s just been kind of a way to keep the tradition alive, as well as keeping a living thing going and seeing how the folk arts of the past can still influence people to do some artistic exploration themselves,” Walton says.

He calls folk art, especially forging, meditative and “something to keep the creative ideas flowing.” And it’s not supposed to be perfect (which is discouraged, if not impossible). There’s wonder in the handmade.

“Sometimes we’ll have very intricate spoons—and they’re ‘just’ spoons,” Walton says. “But in reality, they were able to tell the amount of work that someone put into it, and their ability to learn from their previous mistakes, and the dedication that went in to make something so beautiful.”

Susag admits it’s a challenge, bringing things into being like this.

“Putting [metal into] the forge, watching it, pulling it out, hitting it to a shape that you want or hope that you want, and then you put it back in,” he says. It’s the ultimate satisfaction. “You start it out with just a square piece of metal and then you end up with an ax or a knife blade or a hook tool for bowl turning.”

Woodworker Alex Clarke from Madison, Wisconsin, recently forged her first large fork at Vesterheim. She’s interested in forging nails and furniture hardware.

“Blacksmithing is a really incredible craft that humans have been doing for a very long time,” Clarke says. And, perhaps most importantly:

“Hitting hot metal is fun!”