Akron, Ohio has been a hotbed for jazz in the Midwest since the 1930s. Its central location between bigger cities like New York and Chicago made it a perfect stop for traveling musicians. Many renowned artists, including Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald, performed in Akron as they passed through; but there was also a thriving local scene, the roots of which can still be felt today.

For much of the 20th century, Akron was an industrial powerhouse. People flocked to the “Rubber Capital of the World” in search of jobs causing the population to jump, growing from 70,000 in 1910 to nearly 210,000 by 1920. Akron’s Black population increased eightfold in that time, and many of them settled along Howard Street between Downtown and West Akron.

Where It All Began

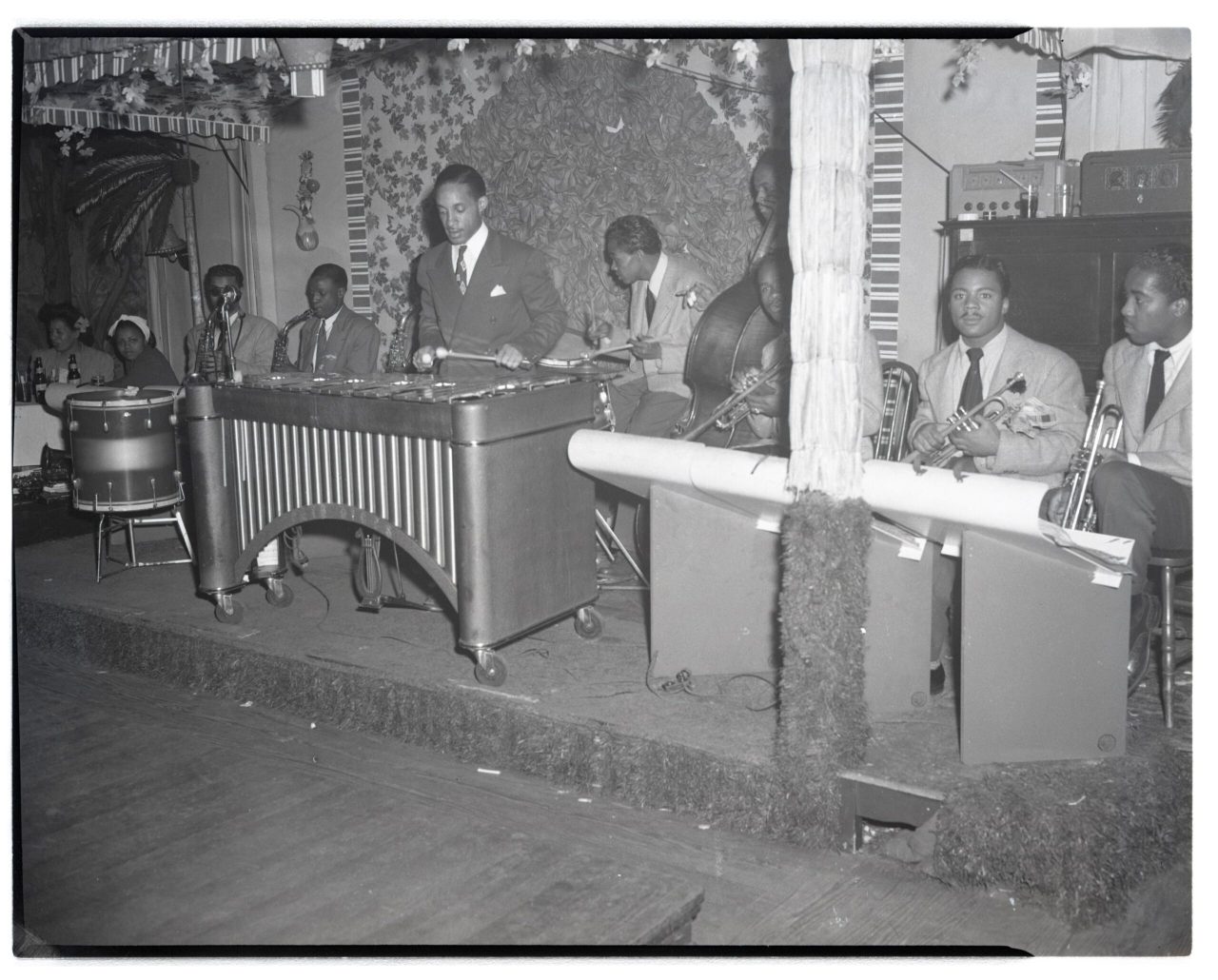

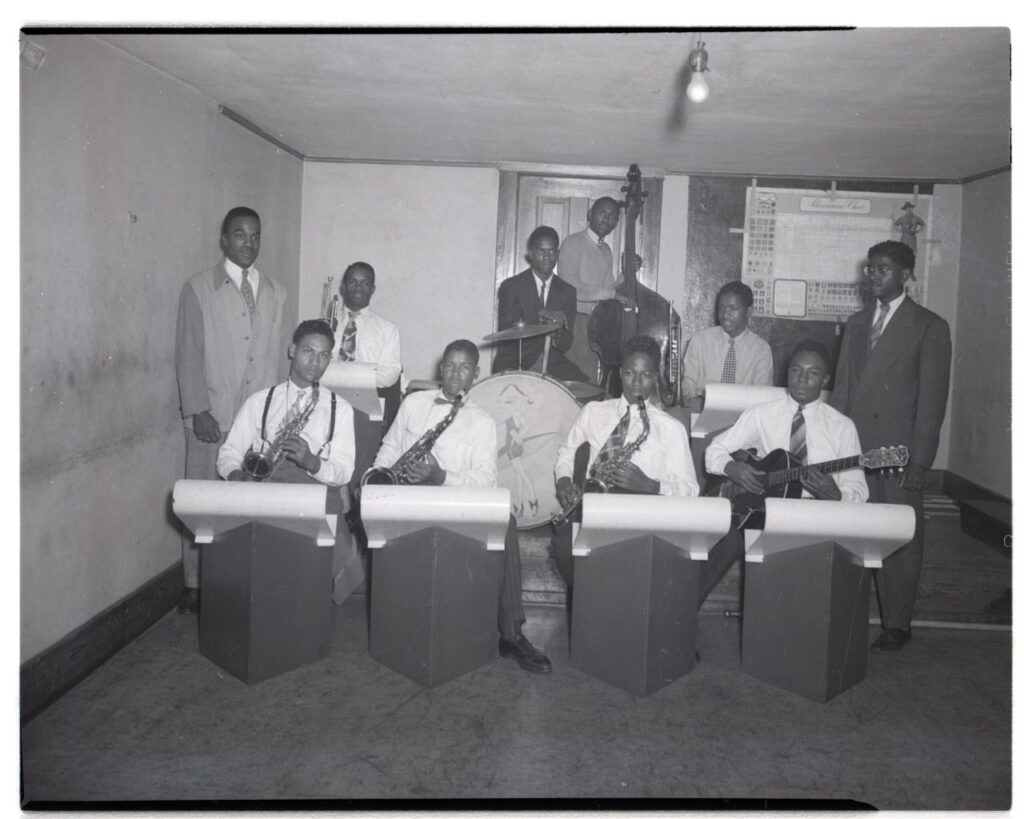

This neighborhood – dubbed “Little Harlem” – became the center of the business and entertainment district along Howard Street, with Black-owned hotels, restaurants, clubs, barbershops, and beauty salons that served the tight knit community. According to the Ohio Informer, Akron’s short lived Black newspaper, there was always music and dancing at the clubs down “Rhythm Row” from the Cosmopolitan, to the Hi-Hat Club, to Benny Rivers, just to name a few.

By the late 1960s the rubber industry was dwindling and much of Howard Street, like the rest of Akron, was in decline. A 1968 “urban renewal” project to build a highway spur linking Akron to the larger interstate network would seal the fate of Howard Street. Construction on the Innerbelt began in 1970, resulting in the destruction of the predominantly Black neighborhood within the decade. Adding salt to the proverbial wound, the project was never fully completed and is now mostly abandoned. In 2023, the City of Akron issued an apology for the lasting harm the project caused for generations of Akronites.

The loss of the Howard Street neighborhood was devastating but it was not the end of the jazz scene. It lived on in small clubs and church basements, and through the people who continued to play anywhere they could.

Where It Lives On

When Justin Tibbs, a local saxophonist and composer, was a teenager in the 2000s his mom snuck him into a blues bar where he met local legends Jim Noel, Waymon “Punchy” Atkinson, and Donald Stembridge.

“Growing up, I always had to ask one of the legendary guys, ‘where’s the jam session at?’, and it would be in some church somewhere. We would go there and play tunes and watch ‘em all play. I didn’t know how big they were,” Tibbs said of his early experiences. This exposure led Tibbs to enroll in The University of Akron in 2006, later joining the Jazz Studies program.

The University of Akron Jazz Ensemble has a direct link to Howard Street. It began in 1978, under the direction of Roland Paolucci, a jazz pianist who played on Howard Street in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He led the program for 22 years before Jack Schantz, a UA graduate and jazz trumpeter, took over for the next 20 years.

The program continues today, co-chaired by Theron Brown, a jazz pianist and two-time UA graduate. Brown moved from Zanesville, Ohio in 2005, unaware of Akron’s jazz history and Howard Street until about 2009, “That’s when I just heard of the names like Punchy Atkinson and Jimmy Noel.”

Brown was part of a Howard Street tribute concert in 2019 at BLU Jazz+, one of Akron’s premier live jazz venues. He played with 91-year-old Jimmy Noel for the first time, only months before his death. Brown reflected, “That’s when I really woke up… There is literally nobody else that can tell the story. We need to go out and find out … there’s a spirit in the air for this music, there’s a vibe, you can call it whatever you want.”

It was similar for Tibbs, who grew up in Akron, “I would talk with them, and they would tell me stories… And I wish I would have had an iPhone at that time to record everything because it’s gone to history… It’s sad that history is gone, but I feel like I’m a part of it in a way because I know their story.”

Jazz for the Future

This sentiment has been shared in recent years as more attention than ever is being paid to this era of history. In 2016, Brown started the Rubber City Jazz and Blues Festival to celebrate Akron’s musical legacy. Now in its ninth year, it has grown into a cultural festival featuring dance, performance art, digital art, and a celebration of Black musical traditions.

Students at The University of Akron are now further documenting this history with the Green Book Cleveland Project, started by Mark Souther of Cleveland State University with the Cuyahoga Valley National Park in 2021. The restorative history project is rooted in the “Negro Motorist Greenbook” published between 1936 and 1966 for Black travelers and documents the entertainment, leisure, and recreation sites available at the time.

In addition to his Jazz Studies courses, Brown recently co-taught a project-based class with Dr. Hillary Nunn, called “Round Howard Street: Telling the Story of Akron Jazz” in which students studied jazz culture in connection with the City of Akron to bring about a fuller understanding of its Black History.

Both Brown and Tibbs credit The University of Akron for fostering an environment for young musicians to meet and play together. “I wouldn’t know any of my buddies that play if it wasn’t for that. It centralized the community in a space even though Howard [Street] didn’t exist,” Brown said. Tibbs similarly reflected, “It’s a whole new generation of musicians… that play original music”. Brown and Tibbs are just two of many musicians playing in the area, all of whom will tell you that Akron still has a unique sound.