For nearly two decades, Rachel Olivia Berg has created large-scale artworks for companies. Think hotel lobbies or resort hallways.

Though undoubtedly aesthetic, the works felt impersonal, branded, commercial.

“You’re telling other people’s stories,” the artist says. In 2023, she moved away from projects like those and focused on stories and communities important to her. So when Berg, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, heard of a Rapid City, South Dakota, tribal health center looking for art, she dove in.

Oyate Health Center

The project’s arts selection committee received maybe half a dozen proposals from Berg—as well as submissions from dozens of creatives across the region.

What’s now a clinic-wide, permanent collection with over 100 pieces was two years in the making, from the open call to installation process.

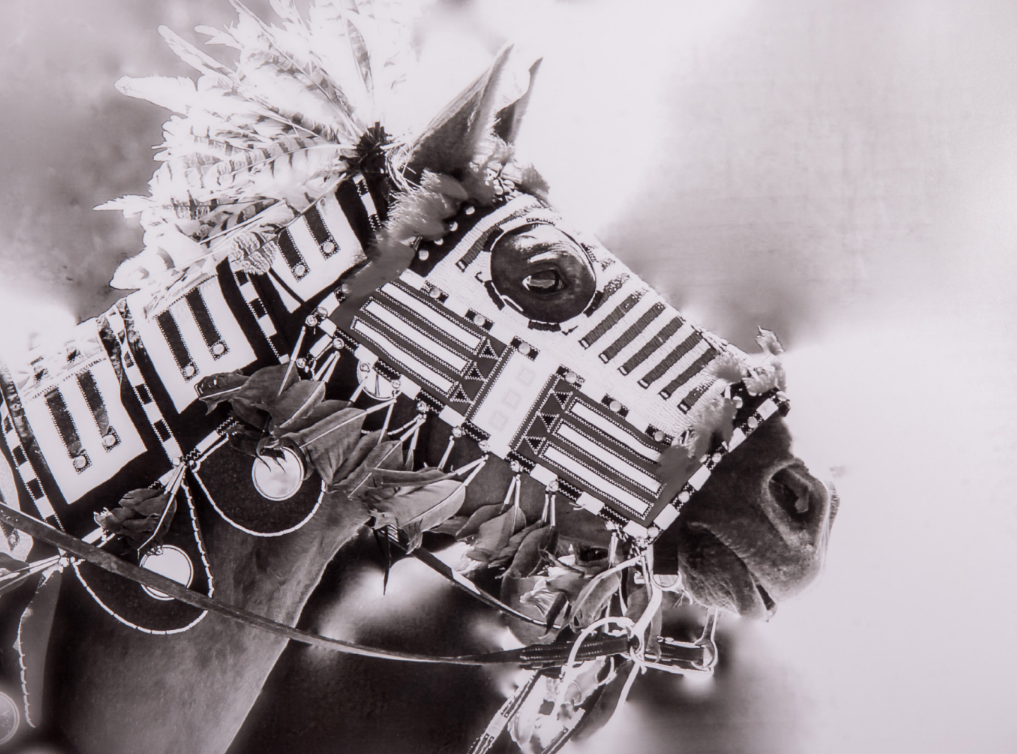

All the selected (and compensated) art pieces focus on culture-specific healing, made by 50-some enrolled tribal citizens from the Great Plains area, from professional artists to community creatives.

“[We] really focused on those visuals of healing and how we as Native people dissect that word—healing spiritual health as well as physical and mental health,” says committee member Ashley Pourier, a museum curator and a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe.

‘Our Own Visual Vocabulary’

The Great Plains Tribal Health Board spearheaded the project.

Taking over management and reconstruction, the former Indian Health Services Center-turned-Oyate Health Center became a brand-new building—with a brand new need for art. But not just any art.

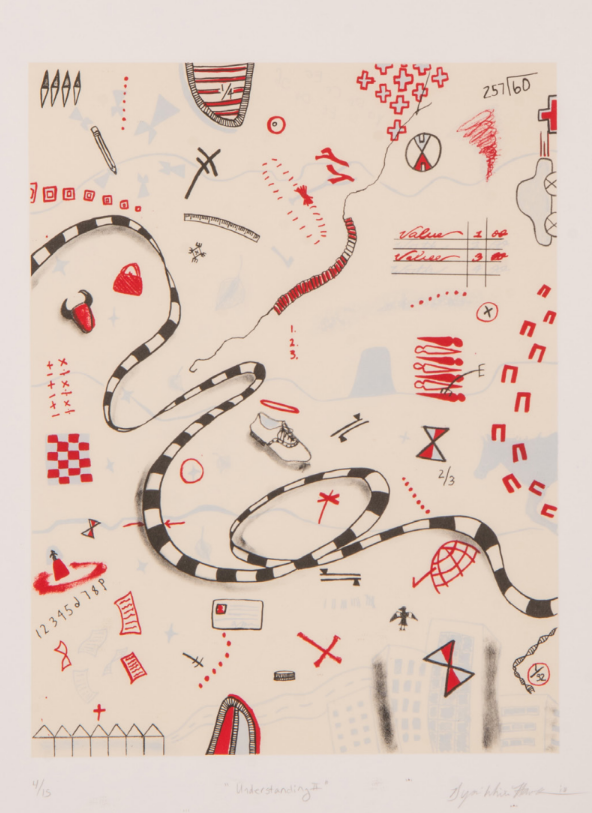

Since the healthcare center is for Native American patients and staff, the art inside needed to be, too. Having Indigenous symbolism about has transformed the space, and what it means to heal inside it.

“It’s important for us, for Indigenous people, to have our own visual vocabulary, to have our own understanding. You can walk into hospitals across the country and there’s frequently flowers or things that are very universal,” Berg says of the more generic art.

“But what’s really nice about Oyate [Health Center] is that we were able to create art from our perspective, things we understand, things we relate to. It helps you feel like it’s your space; it helps you feel that you’re meant to be there.”

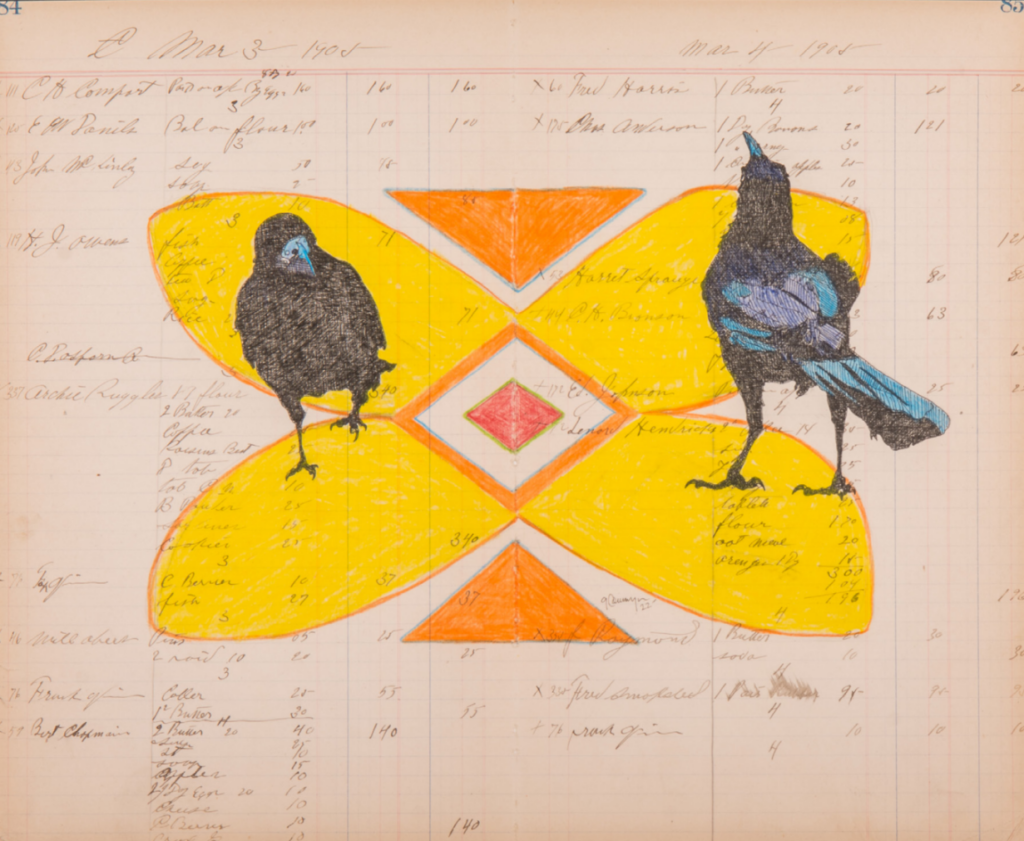

The art collection, from photography to paintings to 3D work, touches on spiritual and cultural understanding.

Berg’s piece, Eagle Buffalo Star, is an expansive wall relief artwork. Made of diamond-shaped resin tiles, it’s a lively, almost moving image of a buffalo and eagle connected by a star.

She started with the idea of traditional beadwork and star quilting: Little pieces come together, creating meaning. Its oranges, yellows, browns and blues—colors of the sky and earth in the Black Hills—shine in the center’s new pediatric area.

“The stars … are hopeful and help us to think of the healing aspect of our connection, of how we’re not alone,” Berg says.

There’s a new and meaningful feeling of community in the space. Berg calls the health center a “hub,” thanks to its art from people across her community.

“It’s literally a museum. It’s a collection,” Berg says. “It’s not just a building. It’s our building.”