This story was originally published by Project Optimist. For more solutions-focused news, local art, and community conversations from greater Minnesota, visit projectoptimist.us.

Poring over compositions Mary Jo Hoffman created every day for the last 12 years can forever change how a person sees the weeds, leaves, twigs, blossoms, and signs of wildlife found in Minnesota backyards or nearby parks.

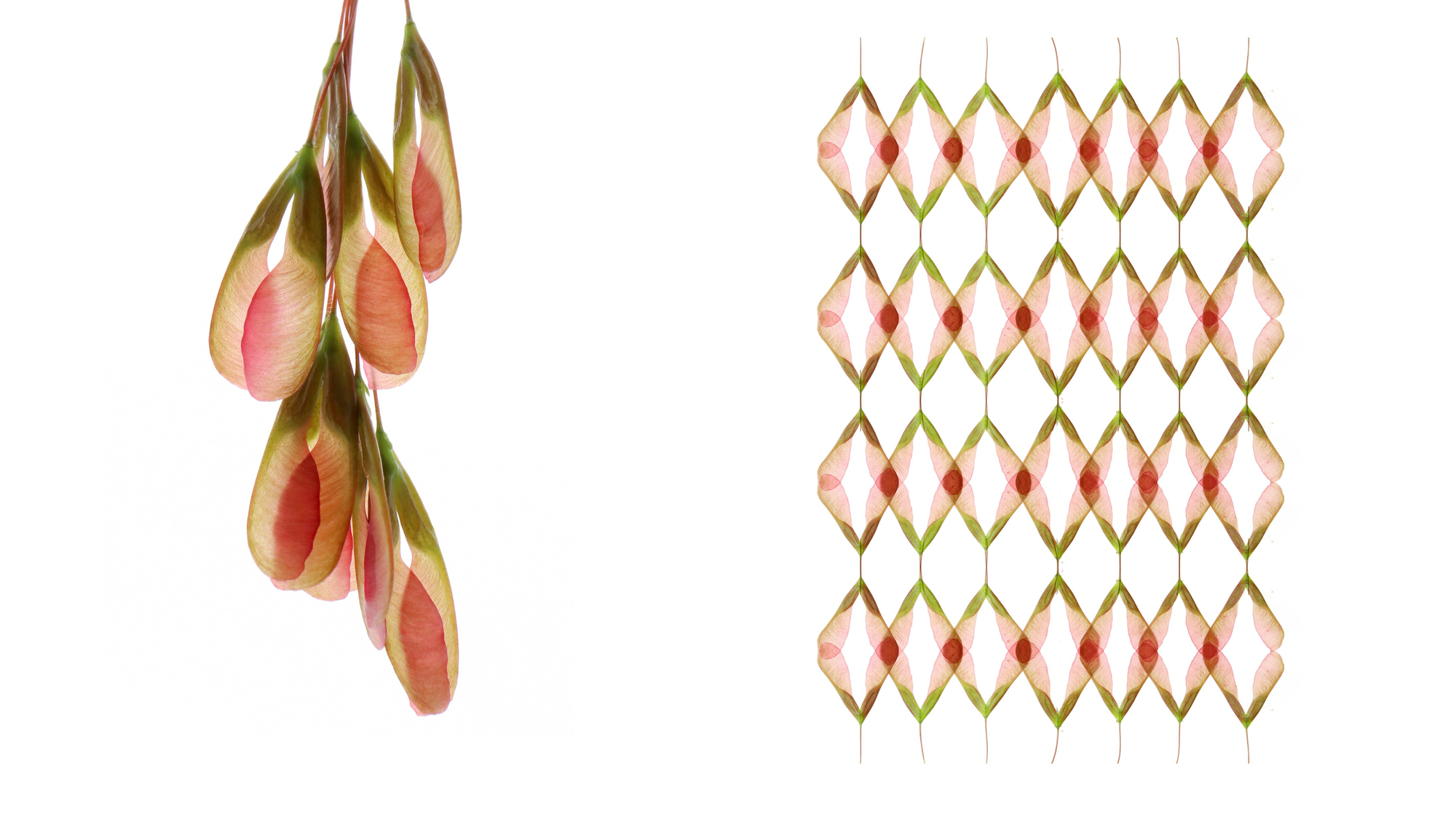

In her hands, petals pulse like fireworks, maple seeds line up like argyle diamonds, perfectly rounded rocks swirl into spirals, and fall leaves become a gradient of color that could make Pantone swoon. More often, though, the self-described minimalist frames her found natural objects simply. White backgrounds let their organic curves, textures, and shapes instill a sense of wonder.

“I originally envisioned a one-year project,” said Hoffman, but it became a way of being — of celebrating her everyday world with deeper appreciation.

Her work quickly inspired others, and her new book, “STILL: The Art of Noticing,” from Phaidon, a global art-book publisher, sold half its original print run before it came out May 1. It includes 275 images from her library of more than 4,000 photos.

“It blows my mind,” Hoffman said of the opportunity and the book’s early success. “This was thrilling.”

It surprises her, too, how it stemmed from ordinary walks with her dog and her commitment to a daily nature-inspired composition, which is often created in her Shoreview kitchen where she gets the best natural light. She craved a creative project after the youngest of her two children began grade school.

Before that, she worked for 17 years as an aeronautical engineer for Honeywell.

When patterns and orderliness show up as gradients and grids in her compositions, that’s her love of math and science coming into play.

Within six months of launching her STILL blog and posting her compositions on social media in 2012, Hoffman was featured in Martha Stewart Living magazine. In 2016, she did a design collaboration with Target for bedding. Global companies from around the world also have sought her artwork for hotels, corporate offices, cruise ships, and even an opera house.

Learning to See More Deeply

Her key to success comes from the non-stop commitment to create — her “dailiness.”

“Dailiness is a superpower,” she said. “Everyone can do it, but no one does it.”

The once-a-day deadline motivates her to truly pay attention to the world around her as she gathers natural objects to arrange and photograph. If she is watching for berries on boulevard trees or feathers dropped by bluejays when they molt, she avoids going into auto-pilot mode during mundane tasks such as dog walks or running errands.

The “art of noticing” changed that, especially as the years rolled on and she needed to find fresh ways to see and showcase the ephemeral seasonal subjects that had become familiar. Her annual photos of lilacs might have them voluptuously mounded together, organized into color-coded rows, sprinkled into a moon-like crescent, or featured a single blossom.

“See past the ordinary and re-see it,” she explained.

Pushing Past Perfectionism

While some days she has time to play and experiment — sorting, piling, sifting, or clustering materials into lush aesthetic arrangements — other days leave little time to fuss, doubt, or do anything over. That, too, can lead to interesting outcomes.

One day with time running out and seasonal materials scarce, she scooped dead daddy long-legs from spider webs on her deck. She spaced them out in consistent intervals against the white backdrop, each one with legs sprawled in different postures.

“The inner critic would have said, ‘That looks gross,’” Hoffman told a group of women at a workshop she hosted earlier this year, but she said it became an interesting piece that she wouldn’t have ordinarily tried.

She also embraces the hip-bump, a trick a magazine photographer taught her. After finishing and photographing an orderly composition, she’ll bump it for a new effect. When she posts both photos — orderly and jostled — and seeks feedback, it’s almost a perfect split between viewers who prefer a precise composition versus something loose and more chaotic.

“Dailiness overrides perfectionism,” she said. “It makes the process more sacred than the product.”

Mary Jo Hoffman“Dailiness overrides perfectionism. It makes the process more sacred than the product.”

Highlighting Minnesota’s Micro-Seasons

As Hoffman documented nature, she noticed it followed distinct cycles. As winter let go, red dogwood branches would brighten, pussy willows and catkins would appear, maples would blossom, and a cascade of other flowers that followed the same order each year.

She then discovered that Japan had an ancient calendar with 24 seasons and 72 micro-seasons, which changed about every five days. Each had a label such as “distant thunder” or “frogs start singing.”

Using that model, she made her own list of micro-seasons for Minnesota’s northern Great Lakes region. That helped her organize and choose photos for her book.

“I developed this minute understanding of my own environment,” she said. And that process — that noticing — became the true art.

When she speaks to groups, Hoffman quotes Rick Rubin, author of “The Creative Act.”

“We tend to think of the artist’s work as the output,” she said, but as Rubin puts it, “The real work of the artist is a way of being in the world. The ability to look deeply is the root of creativity.”

Ultimately, her art feels like both a love letter to Minnesota and a vivid reminder to pay attention to everyday miracles and how fleeting they can be.

This column was edited by Nora Hertel and Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten and fact-checked by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten. It is part of Project Optimist’s Biophilia series about nature and design. It’s supported by a grant from Arts Midwest. Learn more here.