Getting your first thobe is a rite of passage for Palestinian girls, and I’ll never forget when I got mine. I was nine years old when Sedo and Taita—Grandfather and Grandmother in Arabic—presented me with the traditional Palestinian dress.

Thobes are floor length with wide long sleeves, usually a cloth belt at the waist, and always traditional Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery called tatreez. Mine had intricate gold tatreez along the neck, chest, and sleeve hems.

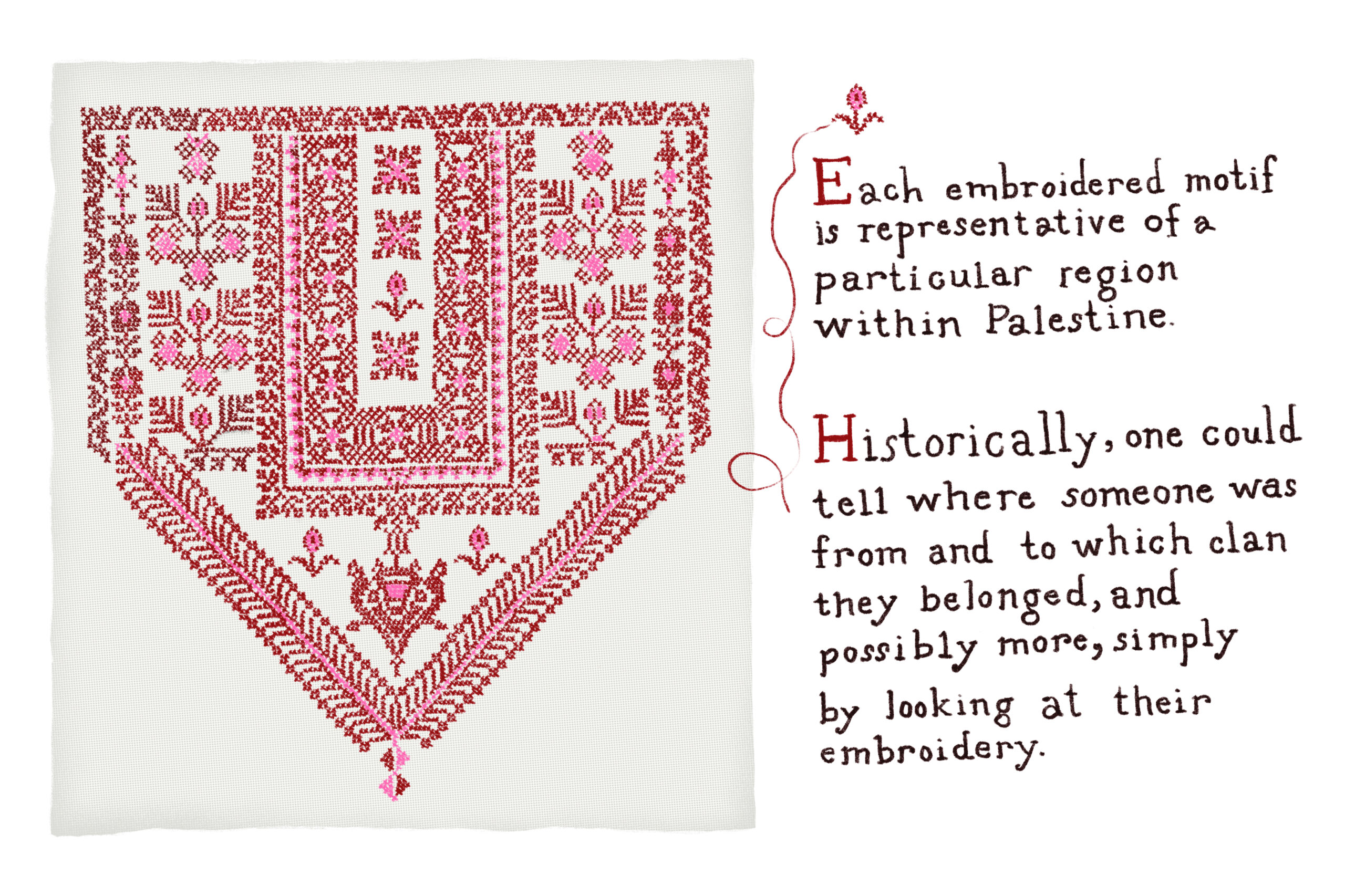

Thobes and the tatreez adorning them can be any color and, like the tatreez motifs on the chest of the thobe, the color and design historically denote what village you’re from, who your family is, and sometimes your wealth, social, and/or marriage status.

My thobe was deep red, representing Ramallah in the West Bank, the area where my family is from. Thobes are often dyed with poppies, which are one of the national flowers of Palestine because its colors—red, green, black, and white—are the same as those in the Palestinian flag. The poppy has come to symbolize remembrance for the dead, the relationship between Palestinians and their land, and resistance against Israeli occupation.

Regardless of the colors used, tatreez is a way of communicating who you are that dates back more than a thousand years. But tatreez isn’t just a historical art—it’s one that’s still being practiced by Palestinians dedicated to keeping the art form alive.

To Honor and Share

Afnan Isleem Algharabli is perhaps better known by her business name, Balady Stitch. Balady means “my country” in Arabic, and it’s never far from Algharabli’s mind.

Born and raised in Gaza until she was 18, Algharabli came to the U.S. to continue her studies, hoping to teach English in Gaza. Her father studied in the U.S. throughout the ‘90s, earning his Ph.D. from Ohio State University, which is part of how Algharabli came to live in Columbus, Ohio.

Although Algharabli grew up watching the women in her family do tatreez, she didn’t have the urge to stitch herself until a few years ago.

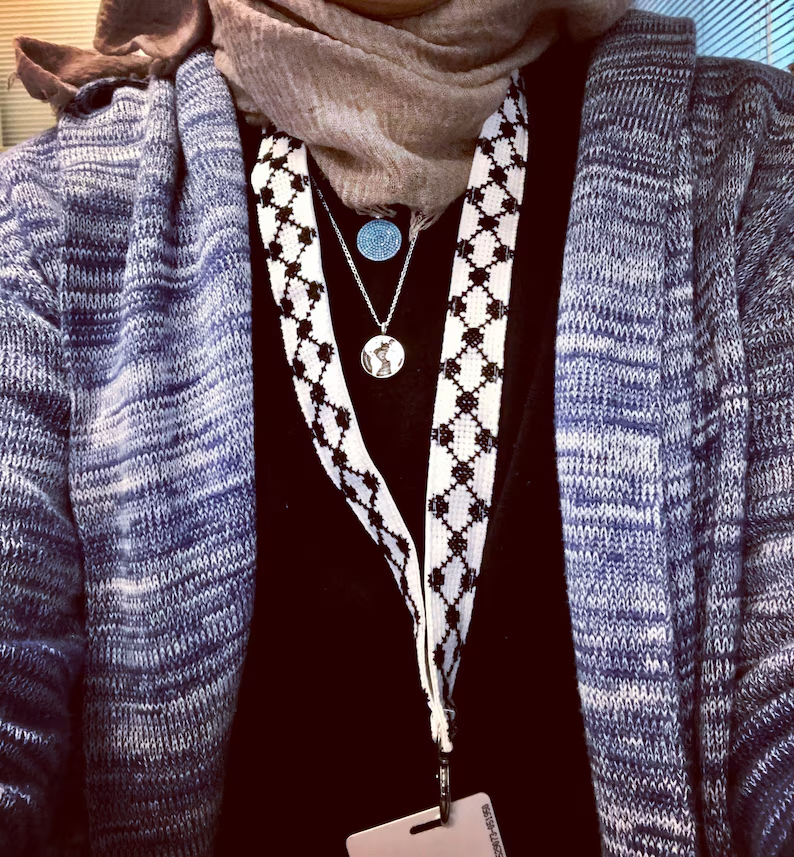

“When I started doing tatreez I wanted to make things people can use on a daily basis,” says Algharabli. “I love thobes, and they’re nice for special occasions, but I wanted a chance where if I’m at the library or in a class or at work someone could say, ‘Oh that’s cool. Where is it from?’ Or, ‘What is it?’ And it’d bring up the conversation of Palestine, and we could start talking. That’s why some of my first items were the bookmarks and keychains.”

Algharabli also has a passion for working directly with women in Gaza and connects with women who do tatreez with help from her mother-in-law. “Even though I know how to do tatreez, I really wanted to work with women in Gaza to support them and give back to my community. ”

However, since Israel began intensifying the genocide against Palestinians in early October 2023, it’s been difficult to stay in touch with many of the makers in Gaza, and still more have had to put tatreez on hold to focus on survival.

“One of the women, her son got killed on the first day of the war and a big part of her family also. That was the last thing I heard from her. Other women, I was able to ask about them in the beginning, but the connection is difficult,” Algharabli, referring to the communications blackout imposed by Israel, which makes it difficult, if not nearly impossible, for Gazans to access cell signals and internet.

From the earliest days of Balady Stitch, Algharabli has named products after the women who inspired them, and now, as the genocide against Gazans continues, the items have become a kind of remembrance to those who are dead or missing, as well as the survivors whose lives are irrevocably changed.

AFNAN ISLEEM ALGHARABLI“I needed to make connections with women in Columbus, and I thought this was a way to do it, to connect over something I love, which is tatreez.”

“I really love reading and learning languages, so I thought about my teacher from Gaza, Salma. She was an amazing inspiration for me growing up, so I decided to name the bookmark Salma,” Algharabli says.

Using tatreez to help people see Palestinians in their full humanity, not just people suffering under violent military occupation, is one of the missions of Balady Stitch.

“Gazans are smart, creative people and I don’t get to hear that as much,” Algharabli says. “The people went through war, but they’re still talking about dreams with limited resources. You cannot imagine the creations they’re able to make.”

The Art of Resistance

Tatreez as a form of communication goes beyond its traditional uses and modern-day conversation starters. It has also been used as a form of resistance. When Israel outlawed and confiscated Palestinian flags, women stitched the flag onto their thobes as a way to say their national pride would not be taken from them. These are called “intifada thobes” or “uprising dresses” in English.

Jenin Yaseen, a painter and textile artist based in Dearborn who goes by Sr7aneh—or “daydreamer” in Arabic, written in Arabizi, a romanized way of writing Arabic letters using a Latin keyboard—taps into this important part of tatreez’s history in her work.

“Tatreez saved my life,” Yaseen says. “I didn’t really pick up on tatreez until the pandemic when I was at one of the lowest points of my life. [Tatreez] forced me to sit down and connect with myself and my ancestors. I didn’t realize how beautiful of an art form it was until then.”

At the same time, Yaseen started learning more about restorative justice, the prison industrial complex, and the realities that Black and other marginalized communities face, especially in the wake of George Floyd Jr.’s murder. Yaseen combined all these into a single project: she tatreezed “abolish prisons” on cloth masks alongside traditional motifs for various cities and villages, including Ramallah, Jenin, Yafa, and others.

“I felt like tatreez was such a beautiful way to show solidarity, similar to how our ancestors used tatreez when they resisted,” Yaseen says. “Palestinian identity and activism have always inspired my art.”

And like many resistance artworks, Yaseen’s work has been censored. In November 2023, Yaseen took part in a traveling group exhibition called “Death: Life’s Greatest Mystery” in which she painted and tatreezed large canvases about the practice of green burial in the Muslim tradition. At Chicago’s Field Museum, the display was shown as intended, but when the exhibit reached the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, the section on Muslim green burial was altered.

JENIN YASEEN“I felt like tatreez was such a beautiful way to show solidarity, similar to how our ancestors used tatreez when they resisted.”

The ROM wanted to crop Yaseen’s painting so the part they found offensive wasn’t on view. It depicted a dead Palestinian person wearing a keffiyeh, a symbol of resistance, with a red poppy growing from their stomach and their lower half adorned in tatreez being held aloft by two monstrous figures representing the occupation. In response to this demand, Yaseen painted a larger version of that part of the picture and showed up at the ROM for an overnight protest sit-in that lasted 18 hours.

Yaseen chronicled the direct action on Instagram, writing: “I am NOT censoring the reality of the Palestinian struggle. … Even in death, Palestinian bodies are held prisoner to occupying forces, and as my Palestinian siblings in Gaza are going through a genocide, some bodies still under the rubble.”

The sit-in ended when the ROM agreed, in writing, to show the artwork with no modifications.

Threaded Together

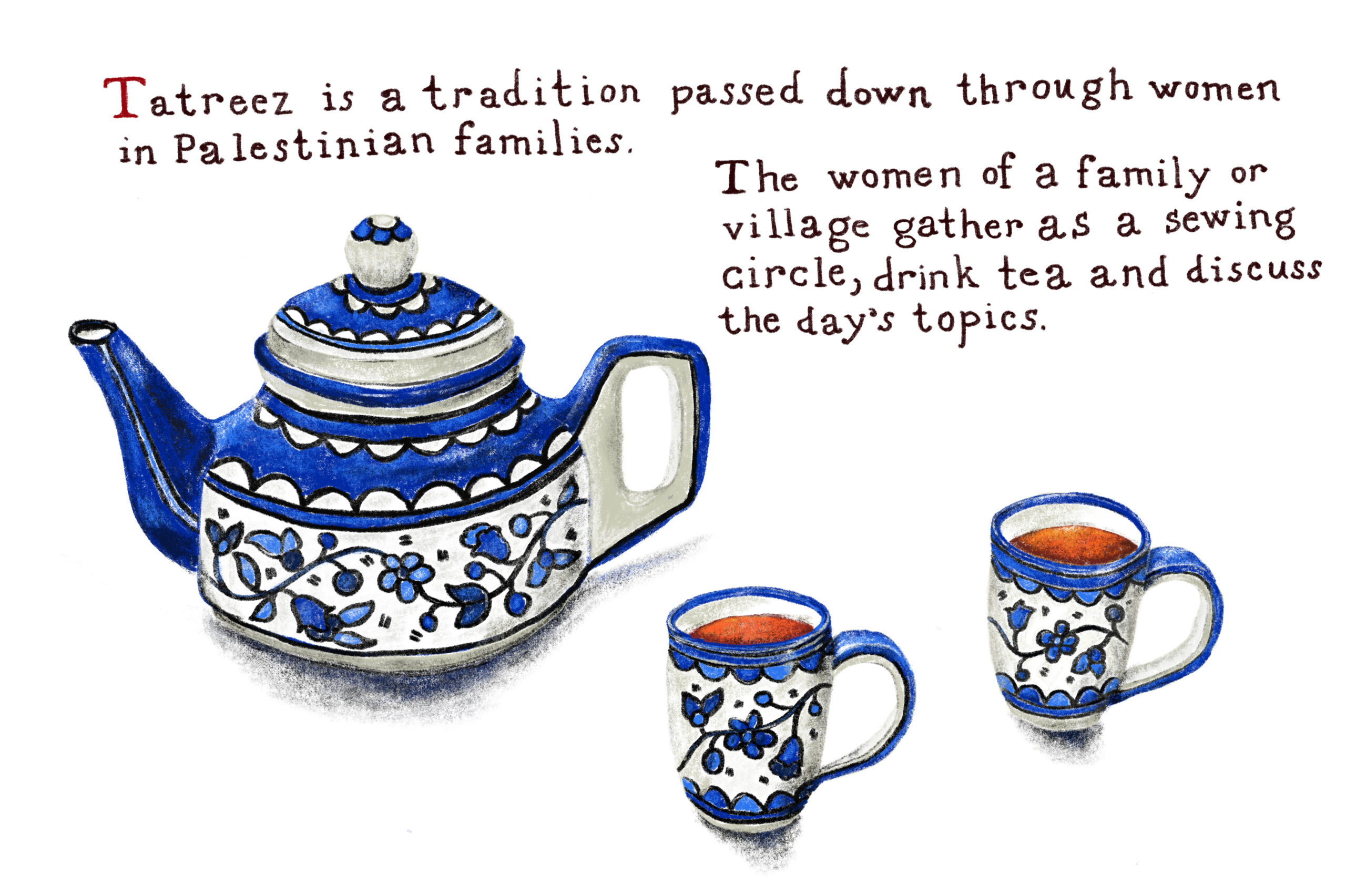

As part of their tatreez practices, both Algharabli and Yaseen lead and participate in tatreez circles. In Palestinian tradition, tatreez circles consist of women tatreezing together, drinking tea, and discussing the matters of the day, be they serious or gossip. It’s about coming together, which is exactly why Algharabli and Yaseen are drawn to them today.

“I needed to make connections with women in Columbus, and I thought this was a way to do it, to connect over something I love, which is tatreez,” Algharabli says.

“I’m leading a tatreez circle in Michigan, and when I learned more about tatreez historically, what really inspired me, especially during the intifadas and during the 1950s and 1960s, was the way Palestinians used tatreez to gather community and inspire them to action,” Yaseen says. “That’s why we host tatreez circles—because it’s much more than making an art form, it’s gathering community to engage with each other in discussion and to be there for each other.”

Though tatreez dates back to the Canaanites, makers like Algharabli and Yaseen are helping keep the tradition alive while also bringing it into the future by putting their own spin on the art form. True to our history as Palestinians, we find ways to maintain our culture against theft, appropriation, and occupation, and make beauty out of the scraps we’ve been given.