The Center for Worker Justice (CWJ) of Eastern Iowa is a first-time NEA Big Read collaborator that brought a fresh lens — and a community of new participants — into the conversation. CWJ is a non-profit that advocates for low-wage workers throughout the region by helping defend workers’ rights, protecting affordable housing, defending civil liberties, and supporting immigrants. “In 2012, local immigrants and people of color came together and said there are a lot of issues we share,” says Mazahir Salih, the Center’s Executive Director, “That’s how the CWJ got founded.”

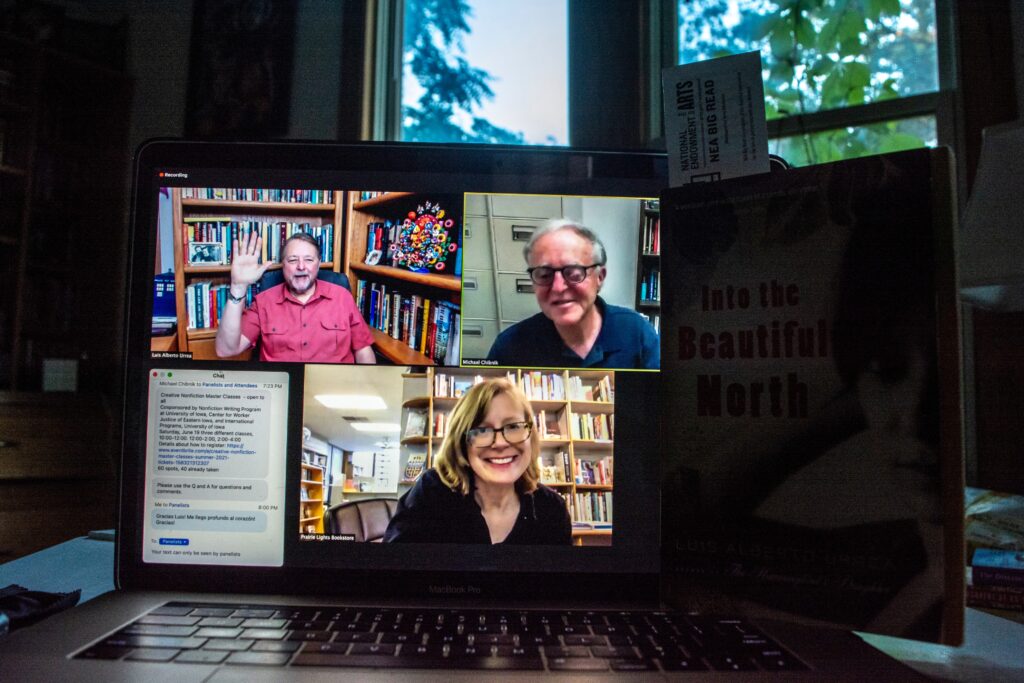

Alongside the area’s public libraries and the University of Iowa, CWJ partnered with NEA and Arts Midwest to present 2021’s Big Read program. Over the course of a month, community members participated in discussions, book talks, writing workshops and presentations, diving into Luis Alberto Urrea’s novel Into the Beautiful North.

From Sinaloa to Illinois – Into the Beautiful North

Into the Beautiful North explores illegal immigration across America’s southern border. It follows a scrappy crew of teenage girls as they seek to recruit seven “warriors” to liberate their Sinaloan town from the narcos who have invaded it. Playing off the plot of The Magnificent Seven (which in turn borrows from Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai) the book is a surprisingly lighthearted hero adventure that highlights issues with border policing, drug trafficking, racism, and cultural dissonance.

The characters travel, led by their heroine Nayeli, from Sinaloa across the Tijuana/San Diego border and all the way up to Kankakee, Illinois. It is an echo of the author’s own voyage. Unlike many fiction writers, Urrea is quite comfortable linking characters, places, and events to his autobiography, he said, sketching out his personal trajectory in his talk at Prairie Lights. And indeed, many of the participants of the Iowa City Big Read project can trace a similar path from south of the Mexican border to here in the Midwest.

Unpacking Meatpacking

With a Tyson plant nearby in Columbus Junction, Iowa, many Big Read participants and presenters have a history with meatpacking. The first presentation in the Big Read, given by Nina Ortiz, focused on the anthropological work she conducted in Columbus Junction, researching the primarily immigrant workers who are employed in the factory. Ortiz led listeners through conversations about pig slaughtering, community gardens, and shared kitchen meals of tostones and ham. The audience of around thirty people gathered virtually to ask about her work and to share their own experiences of life in communities of meatpacking workers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the meatpacking industry was a major focus for the CWJ. “When COVID hit, a lot of members came and spoke to us about how many of them had gotten COVID and it wasn’t being taken seriously in the industry. It was a problem,” Salih said. Most CWJ members are “immigrants from around eighteen countries, mostly African and Latinos.” Many of these members were not eligible for unemployment or federal stimulus funds, despite their contributions as essential workers. In response, CWJ rallied their community and raised over $150,000 in funds that were given directly to industry families struggling because of health or precarious working conditions.

Because of the closely woven relationship to dangerous and underpaid labor and immigrant communities, meatpacking came up again in the emotional and enthusiastic talk given by local author Chuy Renteria, whose forthcoming book, We Heard it When we Were Young, talks about growing up in the neighboring community of West Liberty. He began by reading an excerpt about his family’s relationship to West Liberty and the Louis Rich turkey plant where his father works inspecting turkey carcasses. Chuy teared up while speaking about his relationship with his father and received an outpouring of support from the virtual audience. Participants were enthusiastic to chime in throughout the talk via chat, confirming their own experiences and often painful struggles growing up in a meatpacking town. “Your story about being conditioned by Whites to be ‘ashamed’ of our parents and grandparents is so powerful,” shared participant Jerry Yoshitomi. “As I gained credentials in the mainstream world, my perceptions of my family changed.”

“My belief is that literature can play a big role in creating conversations and providing context on big issues like immigration,” says Chuy. “My experience in West Liberty is that when we stop “othering” people and really live and interact with them is when we grow empathetic to their humanity. And literature and stories are a natural extension of that phenomenon.”

Documenting Heroes

Miriam Alarcón Ávila’s Big Read presentation reflected on her work documenting the narratives of Latinx Iowans and her own experiences as an immigrant. Her spectacular photo project, “Immigrant Luchadores,” provided a comprehensive picture of what being an immigrant feels like in Iowa. In her series, she photographs immigrants wearing customized masks and records their personal narratives of immigration. The masks symbolize “the invisibility of the Latino community, hidden behind counters and in kitchens.” As she displayed her photographs, Miriam shared anecdotal stories of border crossings, linguistic difficulty, and racism.

The audience asked questions such as: “What do you think is the biggest issue facing Latinos living in Iowa right now? What change would result in the biggest improvement?” (Answer: Immigration reform). Another asked: “what can Iowans do to support Latinx communities?” In response, Miriam told a story of a man who heckled her, her children, and her mother at a Fourth of July parade not long after she relocated to the U.S. A bystander came up and apologized after the man left. Miriam asked the bystander why they had waited until the incident was over to express regret.

Miriam concluded by mentioning how Urrea’s work had inspired her. His focus on “the hero’s journey” was explicitly linked to her photography series that “transforms everyday people into superheroes” with masks. She expressed happiness at seeing recognizable stories of Latinx experiences represented and amplified.

Reflection and Fabulation

While earlier events dealt with the themes, communities, and challenges facing the characters of Into the Beautiful North, the student workshop series invited predominantly rural high school students to engage directly with the book over several weeks. They discussed classic literary devices while also examining their own encounters with borders and change. The students produced a series of free writes that addressed specific moments in the book, zeroing in on “fatalism in the Mexican context” in one popular free write. One student wrote: “What ‘everything passes’ means to me is that nothing can last forever…You can’t even stay in one spot forever. People tend to migrate to other countries, which means their time has passed at their old station. I feel like Tia Irma understands this thought very well. She understands that everything that’s going to happen is going to happen, including the girls going to America. She understands that they wish to migrate, and see the world outside of their little village.”

Another well-attended series of public outreach workshops hosted by the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program encouraged participants to produce their own writing. The first workshop dealt with “the archive” and its shortcomings — participants considered the silence of archival data, what it elides and how one researches in that space. One sample archive documented the formation of a Latina group of dancers in Columbus Junction. Community writers used “critical fabulation” to imagine some of the narratives excluded from the record.

A presentation by Janet Weaver continued to examine the role of the archive, by sketching out the history of migration to Iowa. She walked participants through the Iowa Women’s Archive, detailing stories of individual immigrants and talking about immigrant communities throughout the state. Attendees were deeply curious about Mexican experiences in the twentieth century and how the state (and their own cities and towns) have been affected by Mexican migration, which is all too often invisible or erased.

Return to the End

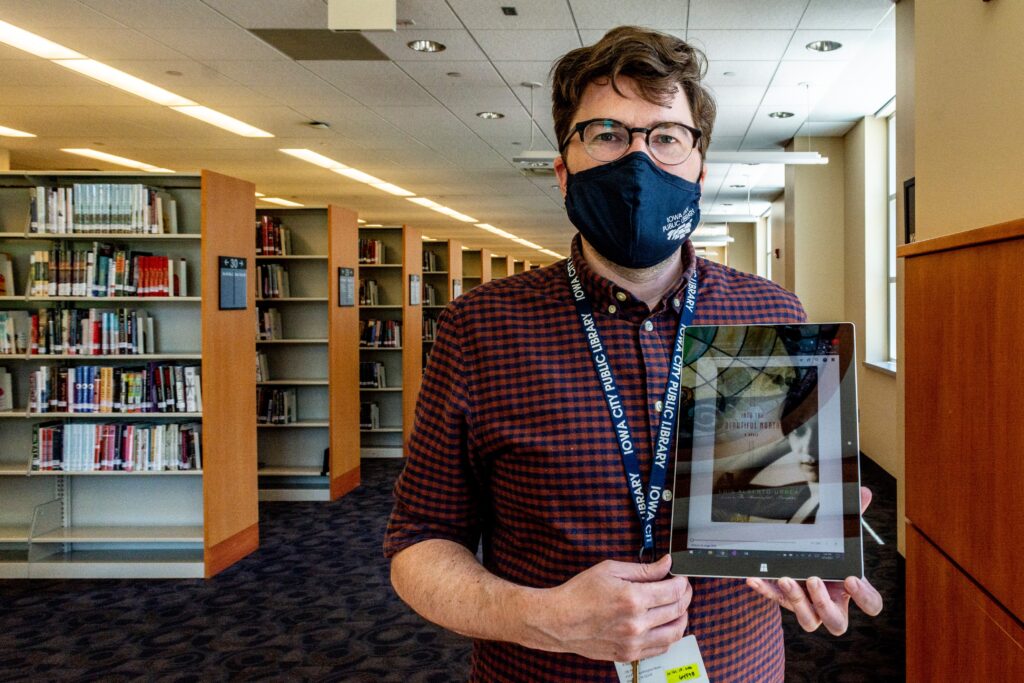

One of the final events returned to the classic milieu of small-town literary discussions: a community conversation at the Iowa City Public Library. Into the Beautiful North essentially ends at a library, which becomes a site of refuge, safety, and resources for Nayeli. The discussion focused on the notion of return, and the idea that many immigrants want to (and plan on) returning to their homes, like Nayeli and her roving band of adventurers. Several readers expressed surprise at this idea, having imagined that the point of illegally crossing the border was to stay on the other side. Rather, immigration can be cyclical, the sort of thing you might do many times.

At the end of the session, everyone shared what they had been reading. Several participants were reading Spanish-language books, sometimes reading both English and Spanish together. The group mentioned the growing Spanish-language and translation section of the library. It seemed like a fitting end to a discussion of a book that, while written in English, frequently incorporates Spanish (and Spanglish).

The Big Read inspired conversations within the diverse communities that make up Iowa City: white and non-white, immigrant and locally grown, rural and urban, university folk and workers in a meatpacking plant. In his talk at Prairie Lights, Urrea said that one of his goals with his work is to achieve a “Mohammed Ali rope-a-dope” — that is, he tries to sucker people into reading Mexican stories by seducing them with good writing. At least for several weeks in May and June, in a little pocket of the Midwest, it worked.

The National Endowment for the Arts Big Read is a national program administered by Arts Midwest that helps communities realize the benefits of reading together. Each year, grants are given to about 75 community reading programs around the country who set up creative events and opportunities for their community to read and discuss one book together. Since 2006, more than 1,600 NEA Big Read programs have taken place in every U.S. state.