If you are looking at an article about do-it-yourself strategic planning, you probably have a project or are in an organization that you are passionate about. Maybe you are at a place where you want some structure around this work, or have been told that you need a strategic plan. You may be new to strategic planning, or are looking to understand this process for yourself as you think about next steps.

If any of those are true (or if you are just curious) keep reading!

This article looks at strategic planning as a process and suggests ways for you to use it to your advantage to strengthen your focus, relationships, and work. It also links to practical resources to help you on your way.

Here are a few high-level concepts to keep in mind about a strategic plan:

-

It should be useful to you.

There are lots of ways to put together a strategy, but the ones that really matter are the ones that help you make decisions to move your organization’s mission forward. In this sense, I often encourage clients to think more about the strategic framework that they need to make decisions in line with the values and goals of the organization. This can be more effective than spending a lot of time writing a list of tasks that won’t actually be used and are out of date as soon as you hit print.

-

It should help you say “no” to things.

Strategy is as much about saying “No” (or “Not now”) to opportunities as it is about agreeing to do things. A good strategy limits your choices in a way that you can clearly explain and focuses your energy on what matters most to your work.

-

It is not a business plan.

A detailed business plan should be its own separate document, with a focus on the income, expenses, and cash flow of your organization. Understanding your financial situation does play an important part in strategic planning though, because it will help you understand where your work is currently most sustainable and powerful. It will also help you understand what needs to change and where there may be opportunity to grow.

-

It is about making time to ask questions together.

Just because the title of this article is about “DIY” strategic planning doesn’t mean you should actually do it by yourself. Gathering a team responsible for driving the process, asking questions, and communicating about your progress will help you stay accountable as you do this work.

Resource: Strategy Screens

-

Strategy Screens: Asking the Right Questions to Make the Right Decisions

Using a strategy screen can help you identify whether a potential new opportunity is right for your organization. This article shows how to evaluate whether new initiatives or existing programs serve a purpose that aligns with your mission.

If you have read this far and determined that you need a strategic plan, let’s get to work.

There are three key phases that I use when engaging in a strategic planning process, and we’ll use these steps to walk through the process:

- An information gathering phase,

- a phase of refining and defining,

- then finalizing and sharing.

One phase should generally follow the one before it, but don’t be surprised if the phases overlap each other. As you refine your work new information may come to light, and as you finalize your plan you may need to revisit your goals and aspirations.

Phase 1: Information gathering

This phase can be the most expansive because you want to take in information in lots of ways – think of it as the wide end of your funnel that you will narrow down to a strategic plan. Gather information about your organization, the communities you work with, your context for the work, and opportunities and threats, as these are all components that you will want to see represented in a strategic plan.

This phase can be the most expansive because you want to take in information in lots of ways – think of it as the wide end of your funnel that you will narrow down to a strategic plan. Gather information about your organization, the communities you work with, your context for the work, and opportunities and threats, as these are all components that you will want to see represented in a strategic plan.

Remember that if you feel overwhelmed, that you don’t have to use everything that you find out in this phase. When you get to the refining and defining work, you will prioritize what to act on, and some things can go by the wayside or be filed away for later.

Key steps for this phase:

The total number of people you could possibly talk to or research you could possibly do can stop your planning before it even starts. By setting some clear needs and parameters for your information gathering, you can set an appropriate scope and timeline for your work. The strategic planning process should engage your project’s core leadership (including your board) and the people responsible for the work as your key stakeholders. Beyond that essential group, the process depends on where you are in your organization’s journey, your needs, and your networks.

If you are a new organization, focusing on your core leadership, staff, select partners can develop a strategic plan that sets a baseline for your work. If you are a more established organization or looking to re-imagine existing programs, it may make sense to engage program partners, audience members, service recipients, or other people connected to your work for more diverse insights. You may also want to take this opportunity to review what gaps you may have in your network, and make intentional efforts to expand your reach.

Once you have determined who needs to be engaged, find the ways to engage them! There are broad ways like surveys that can gather information from a lot of people and have the benefit of anonymity, which can help with honest feedback. There are higher touch ways of gathering information like small group conversations and one-on-ones that can go deeper, but require more preparation and commitment from participants.

To get broad information, an organization-wide (or community-wide) survey with core questions can be a good way to start and get a baseline of information. Some questions to ask in that survey could be: What is working? What isn’t? What are your hopes for the organization? What are your concerns? The responses to these questions will vary depending on the respondent – a board member will have a different response than an audience member, which will be different from an organizational partner or a community member. You’ll want to keep those sources in mind as you compare responses.

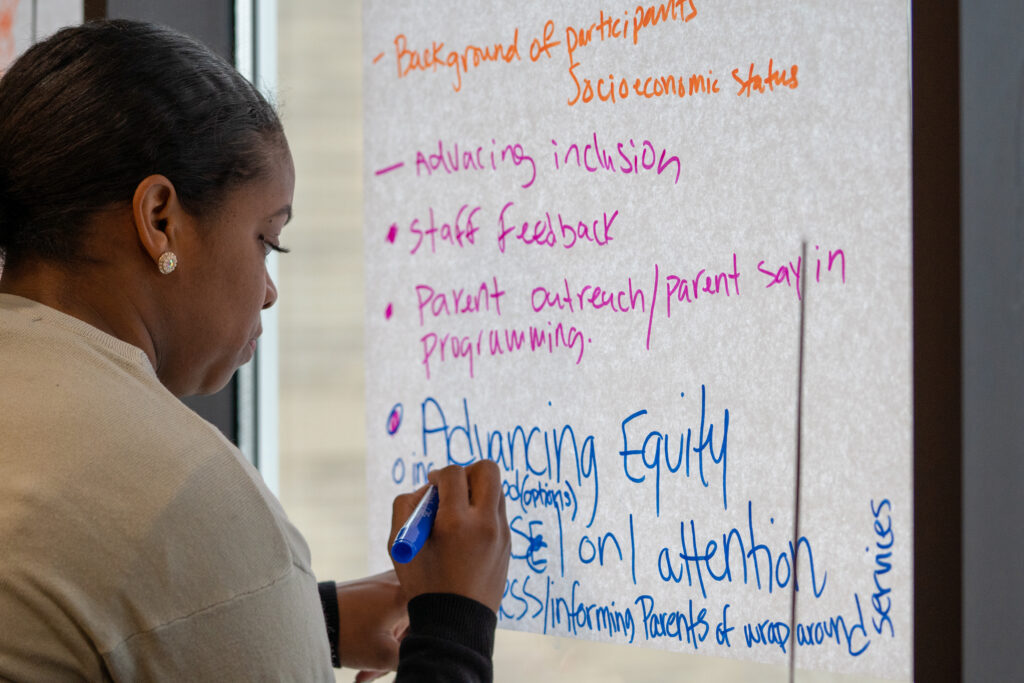

From there, one-on-ones and small group conversations can uncover nuance and get to big aspirations for your organization. An interview technique like the Five Whys can help push conversations deeper in smaller groups. Tools like the SWOT Analysis can provide insight from different parts of your organization about its perceived strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. People come with their own contexts and biases, so remember that you’re building a cumulative and collective vision as you gather this information.

Your work does not exist in a vacuum, and spending intentional time looking at the landscape will ground your goals and clarify your opportunities. Research other organizations in your sector to provide a benchmark to compare your organization against. Ask yourself about who those organizations are not serving, where you differ in approach, and where you see gaps and opportunities to grow. This is a place to use the Finding Your Hedgehog exercise to describe what sets you apart. As you are looking for inspiration, don’t just limit yourself to your own sector. If there are other organizations and movements that you admire or see as effective, ask how their approaches and activities can shape your own work.

It can also be helpful to look at funders or donors in your sector and identify any trends in funding or giving. You can also pull your own evaluation and program data to compare and look at trends. This can be a tricky area of discernment – you don’t want to set a strategy solely based on a funding trend that you don’t control or may shift, but if your work fits in a current trend, you can build your strategy to make the most of that support for your mission.

Your organization should already have core elements of a nonprofit like a mission statement, and maybe vision and values statements. Strategic planning is an opportunity to evaluate how your organization is delivering on those statements, and if there are any adjustments that need to be made. In your conversations and information gathering, ask about what these look like in practice, and how they have evolved. It’s often interesting to ask about shorthand that you use in your organization, or ways that you are talking about your work to different audiences. This can provide insight on natural and intuitive evolution, and give you material to build on for your next steps.

Resource: Mission/Money Matrix

-

Mission/Money Matrix

The Mission/Money Matrix is a tool for visualizing how a nonprofit’s programs and activities contribute to profitability and mission impact. It helps you prioritize resource allocation and facilitates strategic staff and board discussions.

Phase 2: Refining and defining

As you go through the information gathering process, you will gather a broad array of data points and insights that will need to be evaluated to identify what is important. This refining and projecting process may overlap with information gathering, as themes and trends start to emerge. When you come to a point where you have spoken with the right people, done your research, and gathered your information, you will want to be intentional about assessing it to develop the goals and tactics that will make up your strategic plan.

Key questions for this phase:

As you are gathering information, you will probably notice themes developing. Pull these themes out and evaluate why they are coming to the top. Are they aspirational, things that people wish you would do or see as possible? Are they pointing to a deficit in your work or approach that needs to be addressed? Are there any that feel like a big leap? Strategic planning is a time for this assessment, and the ambitious goals from those themes will take time, capacity, and resources to develop. If there are things that need to be addressed right away, don’t wait to do something about it!

I have a friend who likes to remind people when they are planning, “No magical thinking.” It’s a good reminder to ground your aspirations in your current context. This is an opportunity to ask yourself what kind of staffing growth you need to achieve your goals, what community relationships you need to nurture, and how much capacity you have. The Mission/Money Matrix tool is an excellent framework for evaluating your financial resources and capacity, and for highlighting where you can and need to grow.

As you start to work with these big themes and understand the trajectory to get there, put your goals on a time scale. Are they achievable in the next year? In three years? Are they ten year aspirations? For near term goals, use the SMART Goals Framework to put tangible steps and measurable outcomes in place. This will help sequence the steps toward the larger end goal.

This is a perpetual question in this process, especially as you refine your focus and define your goals. If you feel like this middle process hasn’t gotten you enough big aspirations, articulated goals, or helped clarify your values enough to help with decision-making, go back to your information gathering for inspiration. Pausing to ask what is missing can also be the opening question in the next phase, as you finalize and share the strategic plan with your stakeholders and partners.

Phase 3: Finalizing and sharing

Coming through this process you should be able to articulate the work that your organization currently does and how it relates to your mission, vision and values. You should have the themes of your work and future aspirations, and be articulating goals to meet those aspirations. And you should have investigated the capacity you have and what you need for staffing, funding, partnerships, and relationships to meet those goals. All these elements put together, should answer the questions of where you want to go and how you intend to get there, which is your strategic plan.

As you finalize the plan, document these elements into a structure that is legible and useful to your organization, so that you can share it with core stakeholders for feedback before launch. This sharing can be a formal process, where you have rounds of formal revision for a larger process, or a series of one-on-ones with staff and trusted advocates. Ask if there are things that are missing, if the goals are ambitious enough, and if the steps are achievable. This is important feedback, but it is also important to remember that you will be the ones responsible for doing the work.

As you start to work your plan, be prepared for new information and activities to come up that may change the plan’s trajectory. You may find some goals are easier to achieve, or things that are out of your hands slow down one of the areas of work. You may find that the demand for a project or program is less than you expected, or that help is actually needed in some other area. These are not failures, these are new pieces of information to refine and strengthen your work.

In the end, your strategic plan is a living document. You want it to help you act, so that it clarifies your decision-making when new opportunities arise. Make sure that you plan regular reviews of progress towards the goals you’ve laid out (quarterly, or at least every six months). Annual updates to revise the strategic plan are an important part of monitoring your progress. Mark your wins, readjust your goals, and ask yourself if the strategic plan is still working for you. You will want to set a timeline for the plan (I recommend three years as a sweet spot for achievable goals and meaningful progress) and redo the process at the end of that plan cycle.

You will also have a decision to make about how much of the plan you share publicly, and how much you keep as internal benchmarking. A strategic plan is a statement of intent and recruitment tool to drive interest and confidence in your organization, so you may want to share the critical and inspirational elements publicly as part of your communications strategy.

Resource: Finding your Hedgehog

-

Finding Your Hedgehog

The most powerful place to invest your energy is your Hedgehog: the intersection of the work your organization does better than anyone, is most passionate about, and drives support through revenue. This article helps you find your hedgehog.

Conclusion

Reading through this article, you might ask yourself, “Isn’t this just talking to people and writing things down?” And in a very simple way, yes, it is. There isn’t a magic template, but the secret sauce to doing it well is in the curiosity, diligence, and honesty you bring to the process.

Having read all this, you still may want to hire a consultant or a firm to help you out. Having someone hold the space so that everyone can participate is good. Having someone on the outside to ask obvious and poking questions is good. Having someone do research to bring new information in is good. But this is work that can be managed internally, as long as you give yourself the time and have the discipline to do it.

Additional Resources

Arts Midwest; SMART Goals Framework

DesignKit; The Five Whys

Forbes; The SWOT Analysis

Richard P. Rumelt; Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters

Steven Johnson; Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation