I recently drove to Sheboygan, Wisconsin, to visit one of two world-class art museums there. Even if you’ve never heard of Sheboygan, you probably know its neighboring town, Kohler—if only because you’ve washed your hands in a sink made there. A short drive north of Milwaukee, Sheboygan is home to around 50,000 residents and also happens to be an incredible location for a couple of phenomenal art destinations: the John Michael Kohler Art Center (JMKAC) and its new Art Preserve, a one-of-a-kind museum.

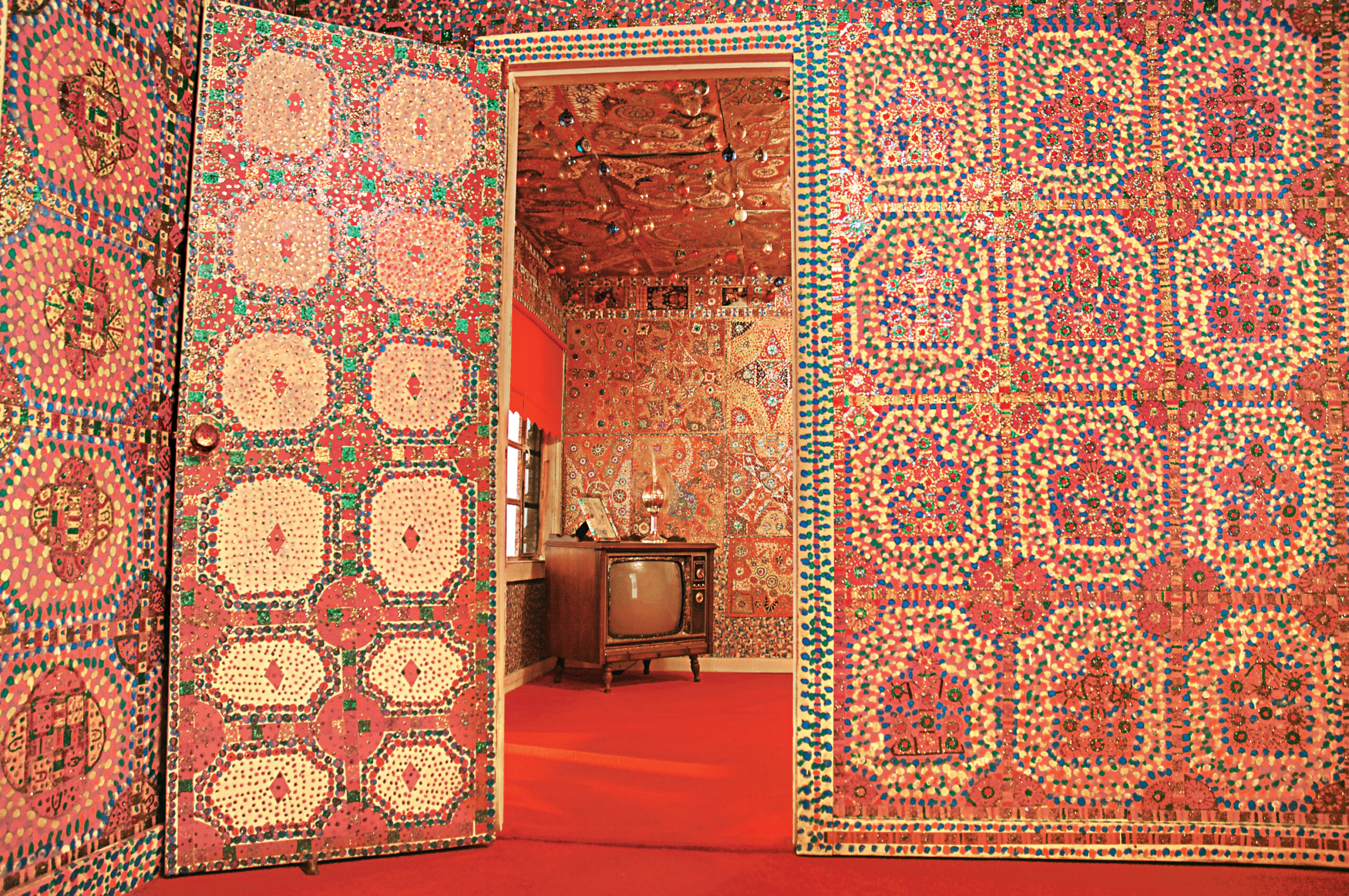

The Art Preserve opened in June 2021 as a permanent home for a very special kind of collection: art environments. An art environment may be defined as many things, from studios to living spaces that artists transform into immersive experiences. This museum houses diverse pieces by self-taught artists, from large-scale, kinetic sculptures built from old farm implements to hundreds of miniature wooden animals in tiny boxes to an entire house coated top-to-bottom in glitter and garland by The Rhinestone Cowboy.

The preservation of arts environments, including local artist Mary Nohl, was long championed by art collector and supporter Ruth DeYoung Kohler II (1941-2020). The director of the JMKAC from 1972 to 2016, Kohler grew the arts center from a local destination into an internationally-recognized institution for contemporary art, the work of vernacular artists, and art-environment builders.

“Ruth saw the arts as a driver of positive social change, upholding the pillars of diversity, inclusiveness, and community involvement,” reads a tribute in the art center’s magazine. She knew that stewarding and preserving the work of underrepresented artists was paramount to furthering that broader mission and promoting inquiry and experimentation.

Commune with Immortal Beings or Be Transported in ‘The Healing Machine’

Now that the Art Preserve’s spaces are filled with eclectic, revolving, and sometimes mind-bogglingly expansive displays, visitors can explore work by artists with diverse backgrounds, motivations, and inspirations, primarily from the U.S. and as far as Chandigarh, India—the concrete “immortal beings” of Nek Chand are phenomenal.

The magic of this museum is that, in an age of digitally-simulated, immersive experiences and Tik Tok-savvy participatory venues, there’s something ultimately so refreshing about immersing oneself in the utterly analog. It’s a privileged insight into the imaginations of artists whose work was often overlooked during their lifetimes—and whose collections would have been dismantled or entirely destroyed if not for this kind of initiative.

One of the installations I’m consistently drawn to, no matter how many times I’ve seen pieces of it installed at the main JMKAC location, is Emery Blagdon’s Healing Machine, an installation originally built in a rural outbuilding on Blagdon’s property in Garfield Table, Nebraska.

When Blagdon was young, he went through a painful period during which he witnessed both of his parents suffer from terminal cancer. In response to that experience, for 30 years, Blagdon was occupied with creating a spiritual place that could channel the healing properties of minerals, electrical fields, and magnetic currents. The sculptures, most of which are suspended from the ceiling, are utterly mesmerizing, as everyday materials like wire and tinfoil twist in the air and reflect the light. Walking through the space, one feels totally transported.

Heading outdoors, Counterculture, one of the season’s temporary installations that consists of seven cast-concrete figures by Rose B. Simpson, is described in museum literature as a series of “witnesses—reminders that the natural world is continuously watching humanity.” Part of the JMKAC’s theme Considering Kin, the sculptures currently stand in wild, wintry field on the art center’s grounds, not only inhabiting the land but beckoning visitors to move closer, connect with the surroundings, and commune with one another.

The work was created for and originally installed on the ancestral lands of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians, in what is now Williamstown, Massachusetts. “The sculptures’ move to Wisconsin traces the path of forced removal experienced by the Stockbridge-Munsee Community, which today is located on their reservation in northeastern Wisconsin, with members also living in other parts of Wisconsin, the United States, and the world.”

A Museum About Artful Spaces—Including Museums

In addition to the artwork itself, as a student of art history and bonafide museum nerd, I admire the Art Preserve’s ability to bring the viewer into its collections by designing the space as an inside-out museum. Within each exhibition space, flat files and sliding racks chock full of paintings comprise the display units. Not only are we invited into the story of each artist, we’re invited into the story of how a museum builds and cares for its collection, literally a preserve of art.

One significant element that has struck me on both my visits to the space is the architecture of the building. The entryway of large, vertical timber beams is designed to mimic a forest one walks through in order to enter the lobby, hinting at the type of transportative experiences that await within. And the interior is open, spacious, and flexible to accommodate permanent exhibits in addition to rotating presentations that are sometimes very large in scale.

One of these temporary installations is Dr. Charles Smith’s vast array of Black figures hand-sculpted from concrete. His figures explore Black experience in the South, where in his home city of New Orleans he experienced childhood incidents of race-based violence, which instilled strong feelings about racism and inequality.

Within each exhibition space, flat files and sliding racks chock full of paintings comprise the display units. Not only are we invited into the story of each artist, we’re invited into the story of how a museum builds and cares for its collection, literally a preserve of art.

After serving in the Vietnam War, Smith purchased a small property in Aurora, Illinois, which became a locus for a burgeoning artistic practice. He first created a concrete archway commemorating the 7,226 African-American soldiers who died during the war, and then gradually covered the entire front of the house and yard with hundreds of memorializing sculptures, naming the site The African-American Heritage Museum + Black Veterans Archive. When Smith decided to relocate the project to Hammond, Louisiana, the Kohler Foundation conserved hundreds of the sculptures, placing many of them in other museum collections.

I’m such a huge fan of ambitious projects and initiatives in places outside of major urban centers. And especially when they are obviously well-loved, funded, and tended, you feel like you’re entering a secret place. There’s an inherent magic of discovery in the experience that is nearly impossible for institutions to pull out of thin air, even with the most compelling artwork or the very best architect signed on. When you layer those things into a unique landscape or community context—one that both complements and responds to its surroundings—something really special happens.