In a self-portrait titled “First Aid Kit” by DarRen Morris painted in 2019, the artist clutches a large, abstract object with fanned white bristles. At first difficult to recognize, the object in his arms is a giant paintbrush. Incarcerated within the Wisconsin Correctional System since the age of 17 and serving a life sentence, Morris clings to art as a survival tool, emphasizing that without it, he would not be able to endure the conditions of imprisonment.

“Art Against the Odds: Wisconsin Prison Art defines art making as not only a creative pastime but a life-saving tool of self-definition for those who are removed from society,” opens the preface of the exhibition’s catalog. The wide-ranging group exhibition, most recently on view at the Neville Public Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin, brings together work by artists incarcerated within the state’s correctional facilities as a way to counter assumptions about imprisoned individuals and the prison system itself.

Debra Brehmer, director of Portrait Society Gallery in Milwaukee, and curator of Art Against the Odds, traces the genesis of the exhibition to a very different project, yet one also focused on the impact of art-making where access to art is often scarce. The program, called On the Wing, met every Tuesday at the House of Peace, a local community center, to draw in sketchbooks.

“It was about gathering, drawing, experimenting, sharing stories, conversing, and building relationships across the divides of poverty and race,” Brehmer says. “Many conversations at the table touched on incarceration. My eyes were opened to the fact that if you are Black and poor in Milwaukee, you’ve had a friend, son, or relative in prison. It was shocking to me that this was such a normalized part of existence.”

Around this time, Brehmer began working with an incarcerated artist named M. Winston to exhibit his work in the gallery. Portrait Society works with artists who have been marginalized, ignored, dismissed, or discriminated against. “M. was a point of entry into the larger carceral world,” Brehmer says. “Exploring art made in Wisconsin prisons felt like a good COVID project, and so many inmates at that time were really suffering during lockdowns.”

Reconstructing a Sense of Being in the World

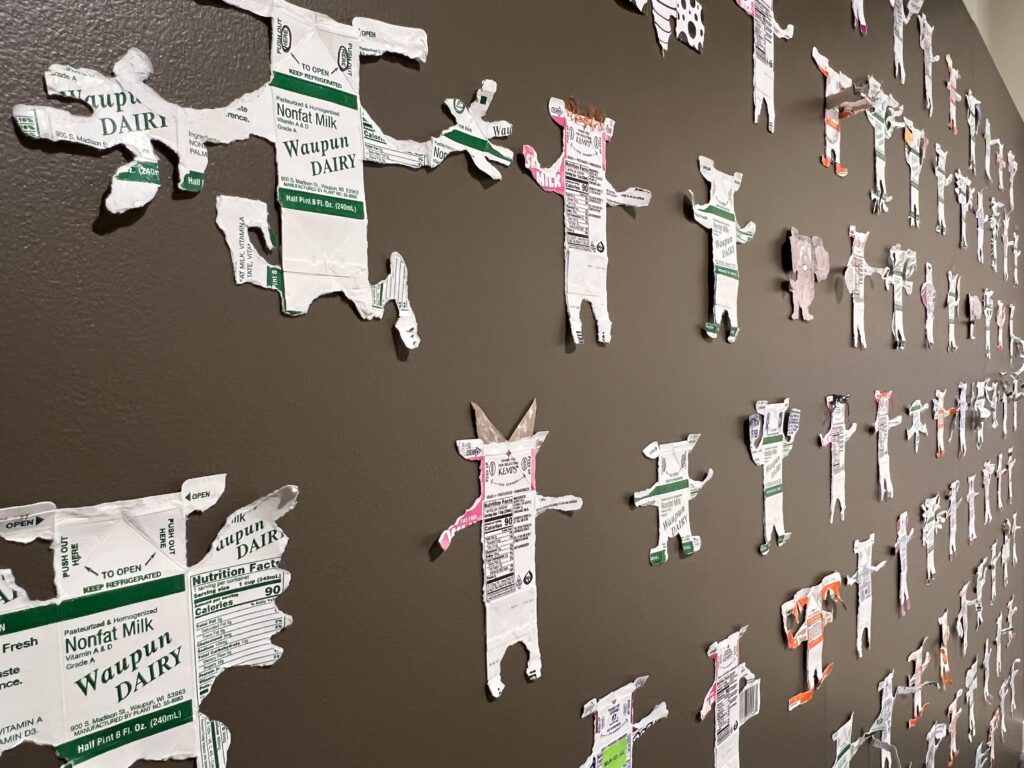

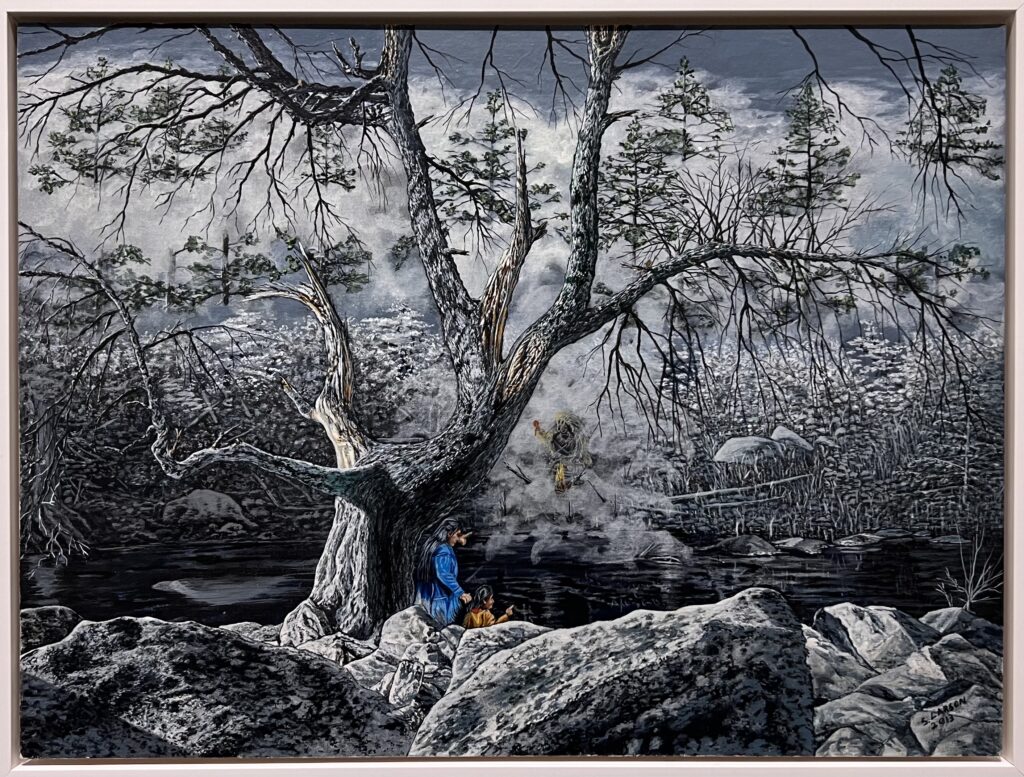

Winston, who grew up in Mississippi, is currently serving a 30-year sentence at Kettle Moraine Correctional Institution and has since become a friend and guide to Brehmer during her research. He makes vibrant acrylic paintings of landscapes, buildings, and abstract color fields, and his sculptures of miniature houses often evoke real places around Milwaukee, made with materials like paper, food boxes, and paint.

Numerous letters that the artist wrote from his cell, which are included in the exhibition catalog, elaborate on his love for walking, a grounding practice in Zen Buddhism, and observations of daily life separate from the outside world. In one letter, dated March 26, 2022 he writes:

This jail is a slave ship without the water. Do you know I have nothing but my mind to keep me going. I have art that may and may not tell my story. I do try hard to tell it. I think that art is something of a person’s soul, our days and nights come and go. But I can do a painting and tell why I did it and what I think it is and that will last forever. If you view art I have done over these long 20 years, you can bet I wasn’t here in the mind. I must do art each day. On some days, because of the size of the painting/drawing, I will do up to six. There’s so much I want to talk about, and I will in time. Let’s see where this ship takes me tomorrow.

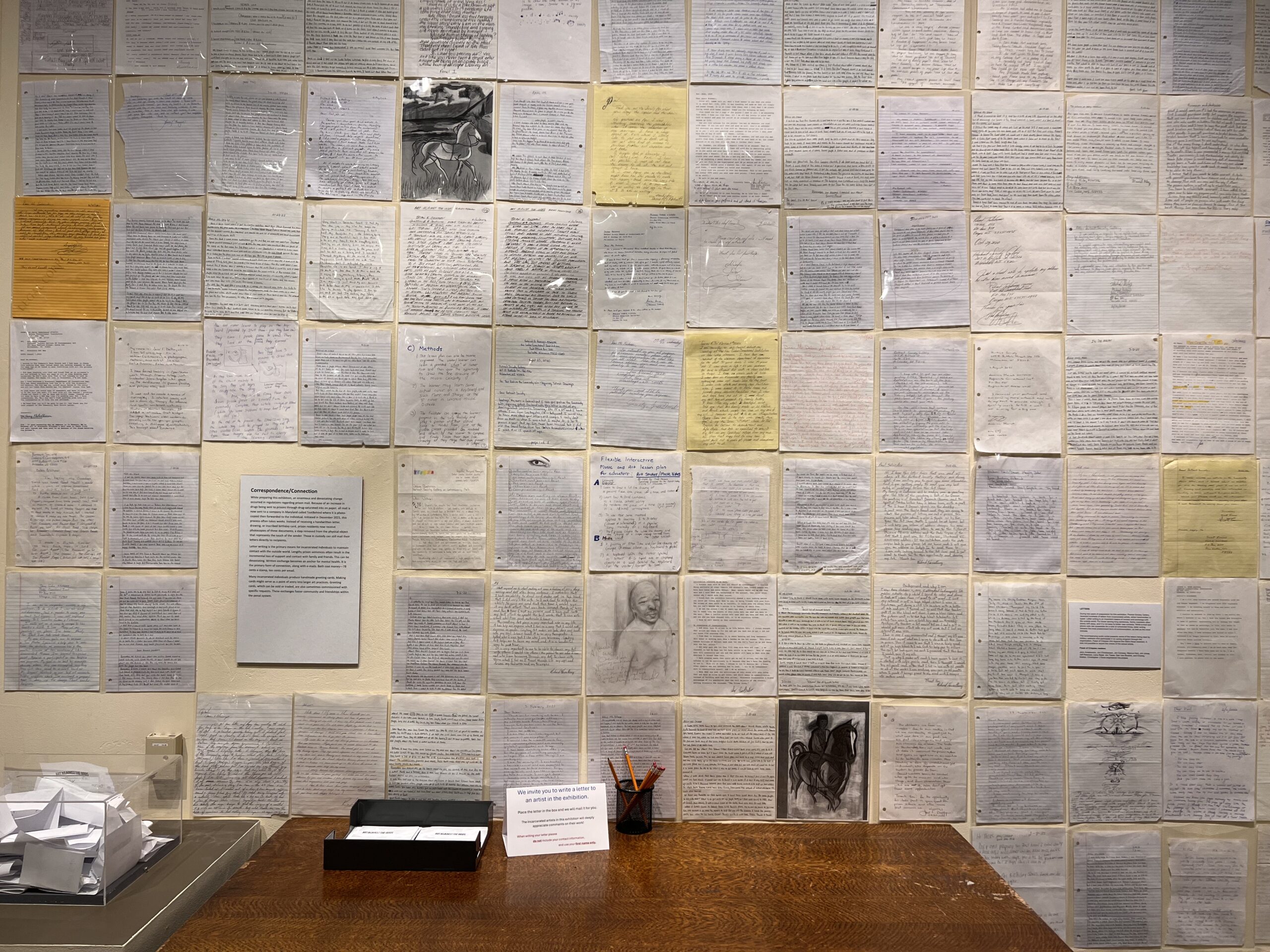

Letters play a core role in the show, with an entire wall dedicated to handwritten notes—a small selection of hundreds sent to the gallery during the process of organizing the show. The display is accompanied by a table and an invitation for visitors to write a letter back to an artist from the show. Audio clips of the letters being read aloud are streamed on a loop through the gallery, a poignant backdrop to artworks that delve into each individual’s personal stories, challenges, and reflections.

An Emotional Outpouring

In January 2023, the first iteration of Art Against the Odds opened in the galleries of the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. “I can only say that the impact of the MIAD show was shocking,” Brehmer says. “We did not expect the attendance: 7,000 people in seven weeks. We did not expect the emotional outpouring. The gallery became a safe space for public conversations that people could not have otherwise.”

Brehmer, who curated the show with Portrait Society Gallery Manager Paul Salsieder, attributes much of the success of the show to the fact that it revolves around accomplishment in addition to the deeply important—yet often dismissed—role that art plays within society. “Art heals and focuses the maker in a space of meditation,” she says. “These artists who turn to art in prison—with no formal training for the most part—find rather quickly that it not only soothes their anxiety but takes them on a journey of expression and self-knowledge, and it builds pride and esteem.”

The visibility afforded to the artists in Art Against the Odds is significant because while the carceral world is hidden, it affects an incredible amount of people in society, from victims to family members to prison staff to social justice system workers and more. The U.S. currently has one of the world’s top incarceration rates—in 2018, it was the world’s highest. Today, approximately 531 of every 100,000 people are in a prison or jail. “Most of these individuals will be released back into the community,” Brehmer says. “If they lack self-esteem and skills, this transition will not be successful.”

Art Against the Odds provides a new lens through which to view the prison system and those living within it. “This is not to deny the pain inflicted by crime, nor the lingering impact on victims, but to privilege redemption and the potential expansiveness of the human spirit,” the catalog introduction continues. “This provides space for hope. Without hope, there is no humanity.”