In many Indigenous cultures, ceremonies and traditions are paired with music. You cannot have one without the other. The beat of the drum represents the human heartbeat. The song is the prayer. The language is the foundation of those prayers. But what if that language was disappearing? How can you keep vocal traditions alive? A Lakota language revitalization project in Bismarck is doing just that. It is called the Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project.

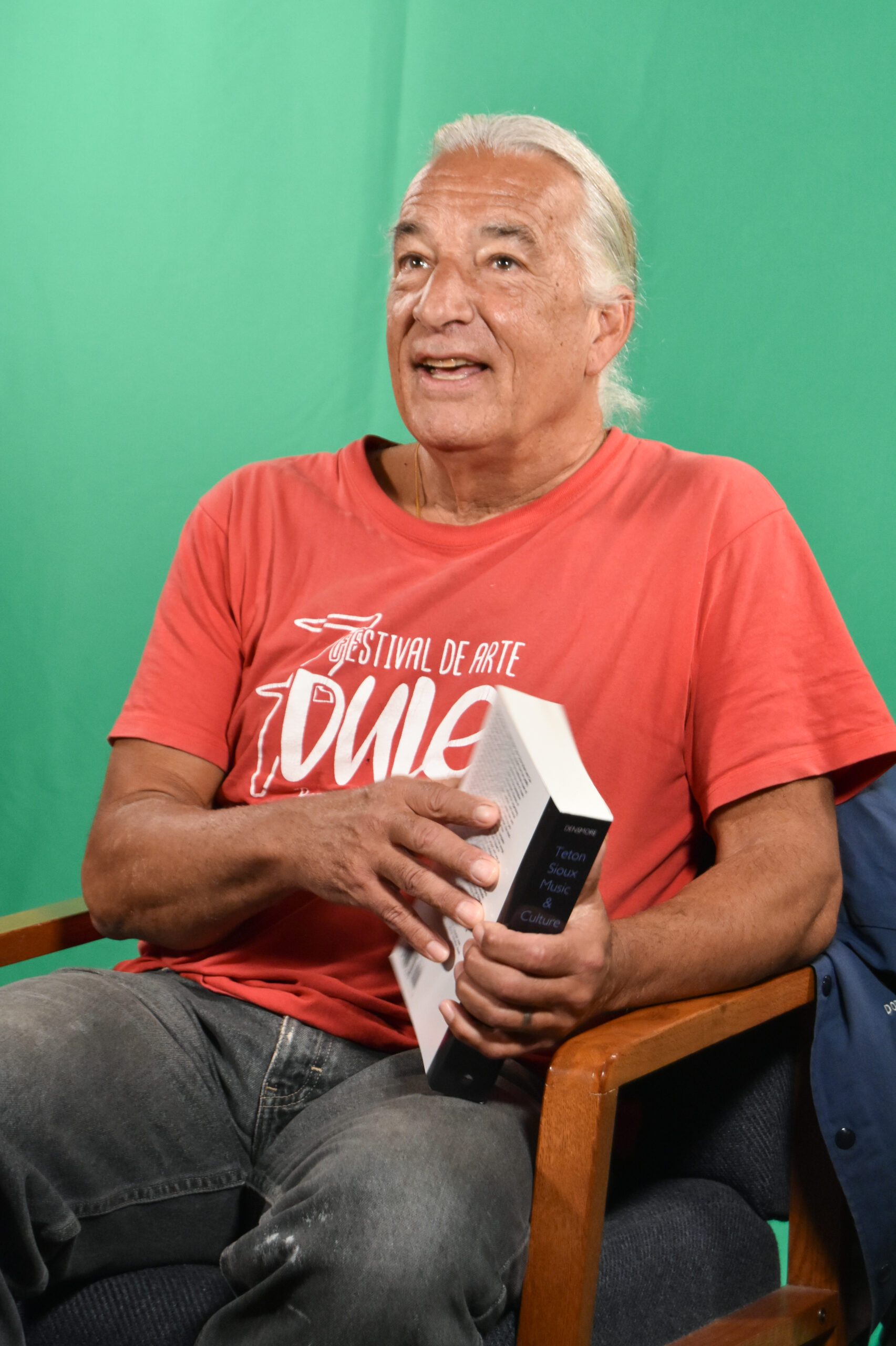

Kevin Locke, the late Lakota author, musician, and educator, who contributed to the project explains the importance of music, language, and culture to the Lakota. He says that the vocal tradition is the foundation of everything. You cannot have ceremony and tradition without music and song.

KEVIN LOCKE, CITIZEN OF STANDING ROCK, PROJECT CONTRIBUTOR“You can’t do anything without music. You can’t do any kind of activity without that music. That’s why the singers have the preeminent station for any indigenous community. That’s what Densmore documented. That vocal tradition which is the foundation of everything.”

That foundation nearly vanished with the growing numbers of European settlers on the northern Plains, as treaties were broken, and assimilation tactics were woven into the fabric of the US Constitution. In 1880, The Civilization Act would prevent Native American tribes from speaking their language or practicing their traditions. Lakota children were sent to government-sanctioned boarding schools who partnered with churches, with a mission of assimilating them to the growing white culture and religion. But instead, they would experience trauma beyond comprehension. For those that survived they suffered with insurmountable pain, a loss of language and a loss of spirit.

Act of Preservation

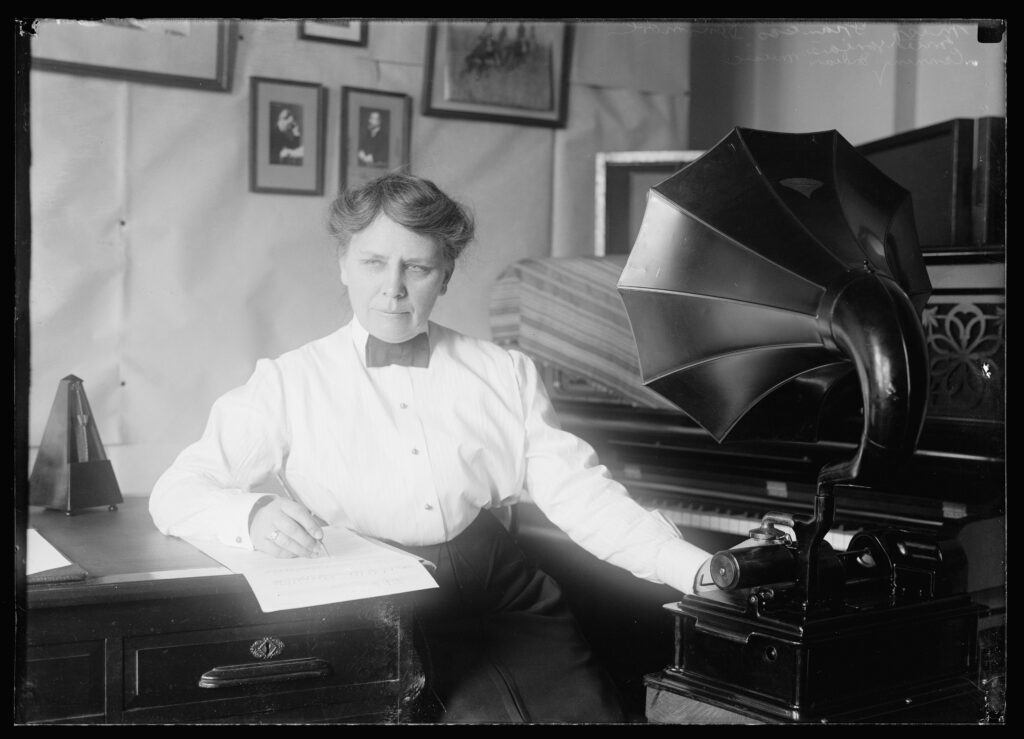

In 1911, a bold Minnesota woman made it her mission to travel to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation to record the Lakota’s music and language before it could potentially be lost forever. Frances Densmore of Red Wing, Minnesota, was a former music teacher who became an ethnomusicologist with the United States Bureau of Ethnology. In an effort to preserve the so-called “vanishing Indian,” she used hand-cranked wax cylinders to record their music. She wrote several books about her experiences, analyzing tribal music, culture and people. Eventually, thousands of these recordings were taken to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for preservation. The quality of the recordings was poor. Today the Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project is an ongoing effort to reproduce those recordings to preserve, promote and revitalize the language and history of the Standing Rock Tribe.

“It’s the one time white man’s technology served us in a good way,” said Courtney Yellow Fat, citizen of Standing Rock , co-producer/cultural advisor to the Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project.

Densmore’s work was groundbreaking for the time. It was extraordinary for such a woman to travel 500 miles from her home to the Standing Rock Reservation to pursue a career in cultural preservation work. It was even more extraordinary that she could convince Elders like Eagle Shield, Red Weasel, Brave Buffalo, Charging Thunder, and Red Fox into recording these songs, especially after the United States government had outlawed the practice of Native ceremonies, dance, and language.

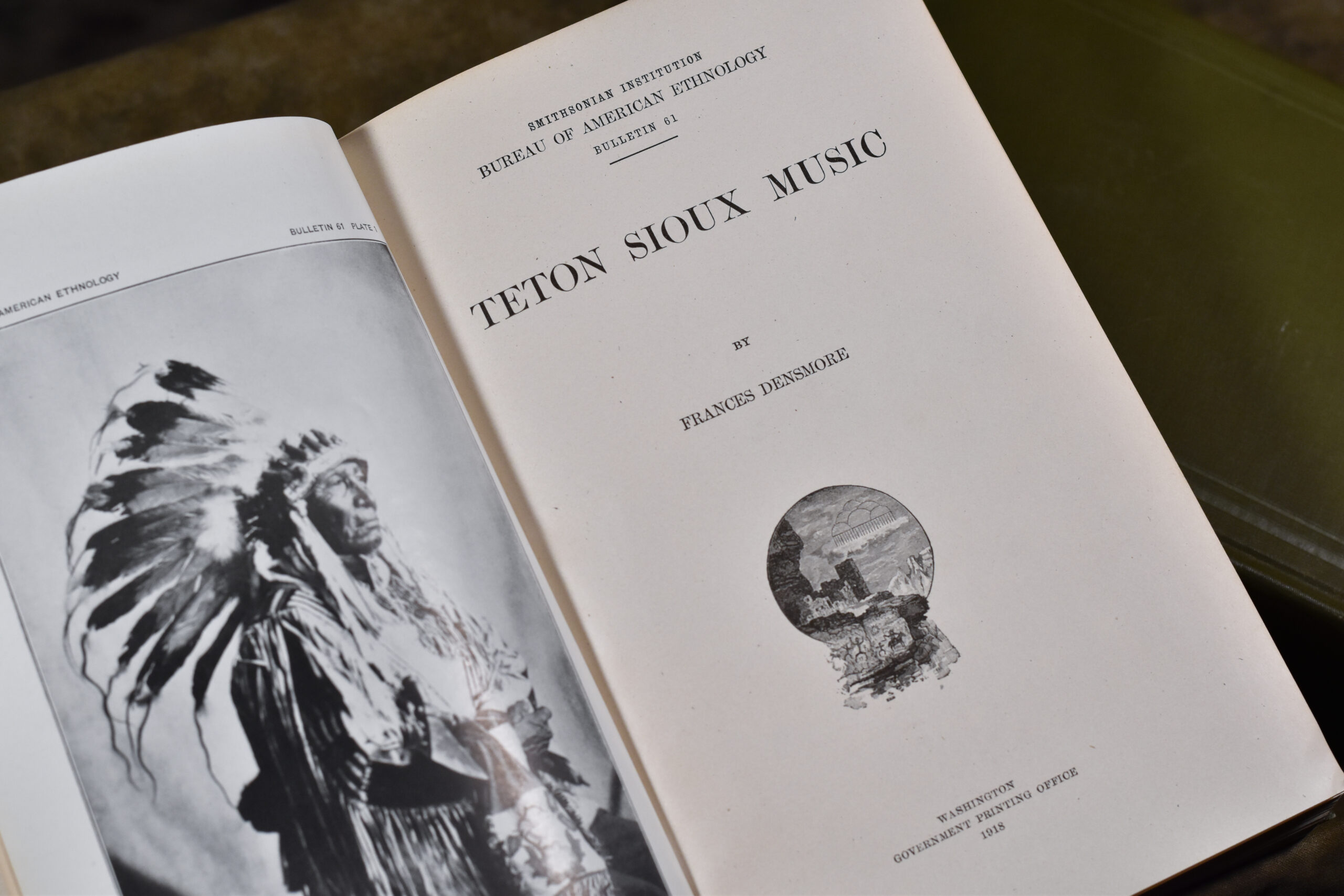

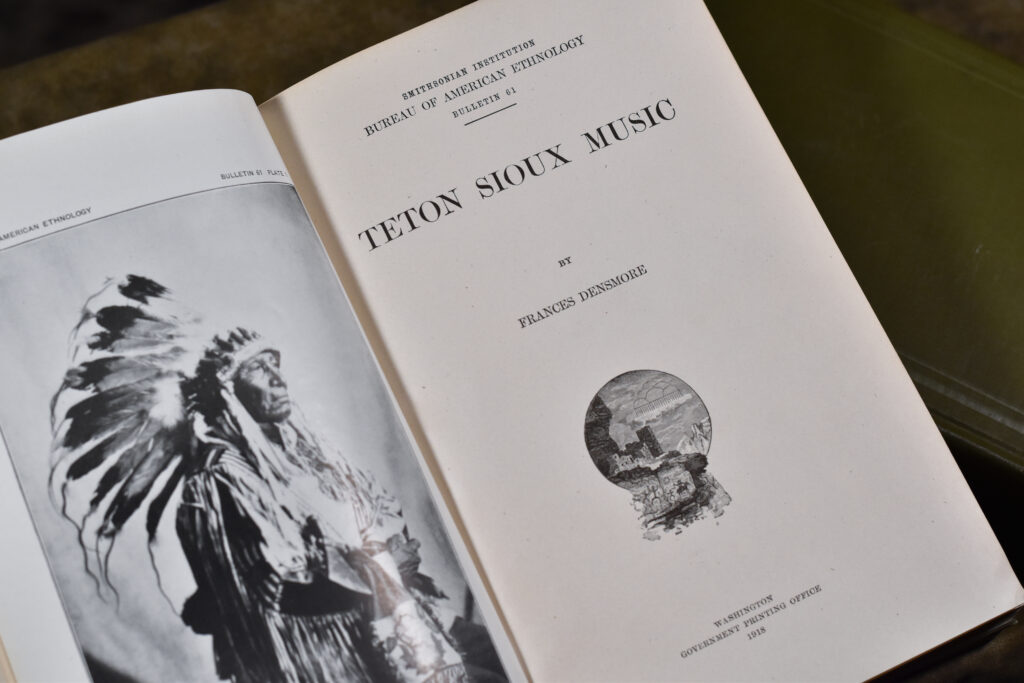

Densmore took several trips to Standing Rock between 1911 and 1914. There she met and recorded more than three-dozen men and women singers, documenting hundreds of songs, and gathering notes for her book, Teton Sioux Music.

As Densmore reflected in her memoirs, recording the Lakota songs was not easy. Conditions were not ideal for making wax cylinder recordings in the hot summers. Also, she was limited to where she could set up her equipment. The drum was so overpowering that either no drum was used, or it was a packing box with a stick. Another challenge was that some songs were ceremonial in nature. Elders did not easily concede to singing for Densmore when there was still a law in place preventing Native American tribes from speaking their language. But she pressed on. Courtney Yellow Fat describes Densmore’s persistence as “a little out there.”

“I don’t know what kind of person Frances Densmore was but to me I think for a white woman to come into an Indian reservation she had to be: one, a little crazy. And two, she had to have courage and be very demanding…the men that sang for her had to have a lot of courage and trust that they weren’t going to be imprisoned or killed or anything like that for doing this,” he said.

COURTNEY YELLOW FAT, CITIZEN OF STANDING ROCK, PROJECT CO-PRODUCER/CULTURAL ADVISOR“To do the things that she did, to go to the places she went, and to meet some of the people she met, she had to be a little bit crazy. She was a crazy white woman! There is no other way to say it.”

Fixing the Sound

In 1996, Kevin Locke met up with David Swenson, owner and executive producer at Makoche Recording Studios in Bismarck, North Dakota. Locke brought original Densmore recordings on cassette tapes. He wanted Swenson to “fix the sound” on them. It was obvious to both of them that something did not sound right. The recordings were scratchy, dark, and muddy. There was something else too, but Swenson could not put his finger on it right away. Then he heard a trill, or what the Lakota call “lele” sounds, a fast high-pitched vocalized tongue trill often used to express emotion. The trill that Swenson heard on the recording was not high-pitched, nor was it fast.

“…it didn’t sound right. And a lightbulb went off in my head, ‘These are at the wrong speed!’” said Swenson, who is the producer of the Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project.

Swenson spent the next 20 years researching what happened to the recordings and communicating this information to the Library of Congress, who were initially hesitant to accept Swenson’s observations. But Swenson’s research showed that Densmore used a pitch pipe in the beginning of her music recordings. Speed and accuracy were of paramount importance to Densmore in order to produce accurate musical notations for her books. Somehow in the process of copying the transcription disc copies made of the wax cylinders by the Library of Congress, the speed was not correct, making these recordings sound slower and lower than they were originally recorded. He said the difference in speed was like that in record players—how 45 rpm sounds different from 33 rpm. The Densmore recordings at the Library of Congress were 10-11% slower than what they should have been. Swenson suspects that they were recorded on one transcription disc system, but later played back on another, and not all transcription discs systems were of an absolute uniform speed.

“Now all of the sudden you can understand words, it was like taking a blanket off a speaker, it was that much clearer. I ended up writing a short paper about how this was found. I corrected the speed. Eventually, after contacting the Smithsonian, I mentioned that I would really like a correct copy of this. It took them 20 years, but they finally did correct it,” said Swenson.

A Living Project

The Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project is about reclaiming Lakota culture, traditional art, knowledge, and religious freedom. The hope is that by re-introducing these songs, the next generations of youth will have easy access to the recordings, in classrooms and presentation settings.

“It fires you up and gets you going. It’s like the feeling you get if you are playing a state basketball tournament and you make a point. The crowd goes wild. It fires you up. That’s how it feels to feel the power in these songs. It fires you up and makes you want to learn more. It makes you sing harder,” said Kendall Little Owl, citizen of Standing Rock/MHA and singer on the Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project.

The research, re-cataloging and re-recording of these songs started in 2021. Thanks to an effort supported by the North Dakota Council on the Arts, Bush Foundation, Dakota Legacy and Humanities North Dakota, these songs are being heard again, and re-recorded with new voices at Makoche Studios in Bismarck. A few of the singers are related to the ones on the original recordings.

Densmore’s book has been digitized and many of the songs and photos of the project can be found on a website, available for free as an educational resource. Students from area tribal colleges participated in apprenticeship programs to learn basic audio/video skills needed to further archive the project and to interview tribal elders. And now students from all over Lakota/Dakota country can use these recordings as a learning tool.

Yellow Fat, who also serves as a culture and language educator at the Standing Rock Reservation says, “These are songs that we haven’t used in a long time. My hope for the future is that these younger singers will pick this up and use them. Just don’t put them on a shelf. But actually bring life to these songs. Give it a heartbeat again because there’s spirits to everything, rocks, trees and songs. There is a spirit to that song.”

The project is available online at the Densmore/Lakota Song Repatriation Project website.

To republish this article for free, visit the ‘Republish Our Stories‘ page and contact our Managing Editor, Angela Zonunpari.